Mark F Rosenberg, PhD | 26th March 2025

Adipocytes are specialized cells that serve as storage for energy, heat production, and endocrine signaling, which are important for metabolic homeostasis.1 Arising from mesenchymal stem cells, there are various classifications of adipocytes, including white, brown and beige adipocytes, which have dedicated primary functions.2 Specific molecular markers are therefore necessary to identify these adipocyte subtypes accurately, facilitating advances in basic research and targeted metabolic development.1-5

The three main types of adipocytes are summarized in Table 1.

| White Adipocyte | Brown Adipocyte | Beige Adipocyte | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphology | Single large lipid droplet | Multiple small lipid droplets | Varied lipid droplet sizes |

| Mitochondria | Few | Abundant | Moderate |

| Molecular Markers |

|

|

|

| Primary Functions | Energy storage (triglycerides) Endocrine signaling (adipokines) Insulation Mechanical support | Non-shivering thermogenesis Energy release Heat production by UCP1 Glucose homeostasis | Adaptive thermogenesis Metabolic flexibility Responses to external stimuli (cold, exercise) Transdifferentiating capacity |

| Primary Locations | Subcutaneous depots Visceral depots | Interscapular (rodents) Supraclavicular, paravertebral (humans) | Spread inside white adipose tissue Enriched in subcutaneous depots |

Table 1: Adipocyte subtypes and their key features. Data sourced from 3,6,7

White adipocytes are the most common type of fat cell, and are characterized by a single large lipid droplet representing over 90% of the cell’s volume. These cells facilitate energy storage and metabolism, with triglyceride storage in white adipocytes being important for non-shivering thermogenesis. White adipocytes can undergo “browning” or “beiging” following exposure to physical and chemical stimuli, including the cold, diet, exercise, pharmacologic agents, certain hormones and a range of cytokines.

White adipocyte markers include:

AQP7 acts as a gateway for glycerol in fat cells. These channels sit in the cell membrane of subcutaneous adipocytes, where they help export glycerol during fat breakdown. Researchers have found AQP7 only in fully developed white fat cells, so they often use it to identify mature adipocytes in their samples.3

Perilipin (PLIN1) is a lipid droplet-associated protein (LDAP) that coats fat droplets inside adipocytes. When hormones signal the cell to release energy, PLIN1 changes shape to allow lipases access to the stored fat, fine-tuning the lipolytic response. Without this gatekeeper, fat cells would constantly leak triglycerides. Researchers rely on PLIN1 staining to detect adipocytes in mixed tissue preparations.3,11

FABP4 shuttles fatty acids through the cytoplasm of fat cells. This small protein grabs long-chain fatty acids and protects the cell from their detergent-like properties. Scientists have consistently succeeded in using FABP4 antibodies to distinguish mature adipocytes from preadipocytes and other cell types.8 While highly expressed in adipocytes, it is also found in macrophages.

Adiponectin emerges mainly from white adipocytes, with higher concentrations in subcutaneous fat than visceral deposits of metabolically healthy people. This 30 kDa protein occurs in various oligomeric forms; it enables energy homeostasis and insulin sensitivity by activating multiple distinct signaling cascades.9

White adipocytes release leptin, coordinating energy balance and appetite regulation.10 By targeting hypothalamic neurons, leptin reduces food consumption while boosting energy expenditure. Leptin is typically quantified using ELISA or Western blotting techniques, which reflect underlying adipocyte function.

TCF21 (Transcription Factor 21) is a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, a unique marker for visceral white adipose tissue (vWAT). Beyond coordinating mesenchymal differentiation and organ development, TCF21 is highly enriched in visceral compared to subcutaneous fat depots. It uniquely modulates visceral adipocyte lipid handling and inflammatory signaling. When TCF21 is deleted in mice, the animals display strong alterations in visceral fat distribution and function—evidence of TCF21's prominent role in maintaining visceral adipocyte identity.12

HOX Genes (HOXC8 and HOXC9) are homeobox genes which characterize subcutaneous white adipose tissue (sWAT). Although initially considered developmental regulators, these genes are found in mature fat cells and craft depot-specific attributes. Studies in humans and rodents have shown higher expression of HOXC8 and HOXC9 in subcutaneous compared to visceral adipose depots. These transcriptional regulators facilitate genetic programs influencing adipocytes' response to insulin and lipolytic stimulations. Intriguingly, HOXC9 controls adipocyte browning capacity, with its expression levels inversely related to the thermogenic potential in subcutaneous depots.13

Figure 1: IHC of mouse adipose tissue stained with Anti-Perilipin-1 Antibody [ARC1122] (A306256).

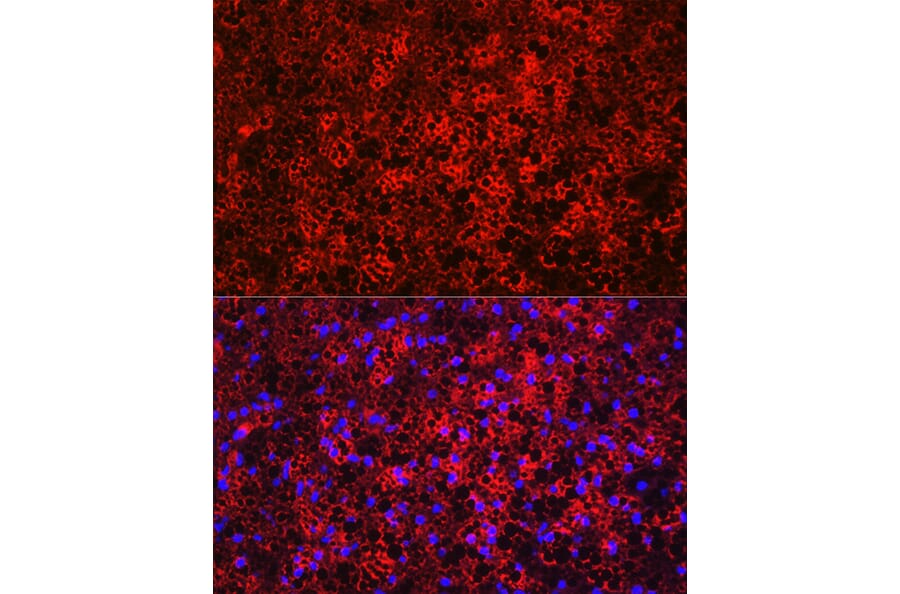

Figure 2: IHC of rat adipocytes stained with Anti-FABP4 Antibody (A12560) in red. Nuclei are marked with DAPI in blue.

Brown adipocytes generate heat, utilizing mitochondrial uncoupling to enable non-shivering thermogenesis. They are found in brown adipose tissue (BAT) and are characterized by large numbers of mitochondria and small lipid droplets within their cytoplasm.

Brown adipocyte markers include:

MT-CO2 (Mitochondrial Cytochrome C Oxidase Subunit 2) is a mitochondrial marker produced in brown adipocytes and, recently, visceral adipose tissue. It reflects the high mitochondrial content and thermogenic activity characteristic of brown adipocytes.3,14

ZIC1 (Zinc Finger Protein of the Cerebellum 1) is a transcription factor that is expressed in Myf5+ lineage-derived brown adipocytes but is absent in beige adipocytes, making it a useful marker for distinguishing the two populations.7,15

UCP1 (Uncoupling Protein 1) is a mitochondrial protein which generates a non-shivering thermogenesis and energy expenditure phenotype.16 This protein uncouples the respiratory chain, enabling protons to re-enter the mitochondrial matrix, mitigating ATP production and thus generating heat. Western blotting and IHC measure UCP1 expression to quantify brown adipocyte activity.17 UCP1 is also found in beige adipocytes.

PRDM16 is a transcriptional regulator that directs brown fat differentiation by controlling networks linked to thermogenesis.17 PRDM16 activates brown fat-specific genes. As well as acting as a marker, PRDM16 can be applied in cell culture experiments to induce brown adipogenesis.18

EBF2 (Early B Cell Factor 2) is a transcription factor, a marker for early brown adipocyte commitment, and an establisher of brown adipocyte identity. This protein works upstream of PRDM16 and regulates PPARγ binding to brown fat-selective genes. EBF2 coordinates chromatin remodeling, thereby establishing brown adipocyte-specific enhancer landscapes. EBF2 affects thermogenic gene expression and mitochondrial function in mature brown adipocytes. Overproduction of EBF2 in white adipocyte precursors promotes a brown-like phenotype, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target for metabolic disorders.19

Additional markers include CIDEA (Cell death-inducing DFFA-like a) and P2RX5 (Purinergic receptor P2X5), which regulate lipid droplets and activate during brown adipocyte stimulation,20,21 while isocitrate dehydrogenase I enhances metabolic flexibility in brown adipocytes.22

Figure 3:UCP1 expression in rat brown adipose tissue analyzed by IHC using Anti-UCP1 Antibody (A15609).

Figure 4:Immunofluorescence analysis of rat brown adipose cells using Anti-UCP1 Antibody (A15019) in red. Nuclei are marked with DAPI in blue.

Beige adipocytes combine white and brown adipocyte features, growing in response to environmental and metabolic stimuli, and having an intermediate number of mitochondria and mixed lipid droplet sizes. Though they are found within white adipose tissue (WAT) depots, they are thermogenic like brown adipocytes. Beige adipocyte formation is induced in response to cold conditions, β-adrenergic agonists or PPAR-γ agonists.2

Beige adipocyte markers include:

KCNK3 (Potassium Channel, Two Pore Domain Subfamily K, Member 3) is a potassium channel that improves thermogenic capacity in beige adipocytes by regulating membrane potential and cellular respiration.23

CD137 is a member of the TNF receptor superfamily and regulates immune responses. acts as a surface marker for isolating beige adipocytes. This protein acts as a surface marker for isolating beige adipocytes from mixed populations, such as by flow cytometry.24

Tmem26 distinguishes beige cells from white or brown adipocytes. Investigations continue as to its exact function in beige adipocytes, but its expression can be measured by qPCR to monitor beige adipocyte differentiation.4,25

PAT2 (Proton-coupled Amino acid Transporter 2/SLC36A2) is a cell surface marker highly expressed by beige adipocyte precursors and mature beige adipocytes. This amino acid transporter detects amino acids and activates mTOR signaling in beige adipocytes. Beige adipocyte differentiation and browning stimuli—such as exposure to the cold or β3-adrenergic receptor activation—increase PAT2 expression. Flow cytometry sorting of PAT2-positive cells from white adipose tissue can separate populations with enhanced beige adipogenesis capacity. Mechanistically, PAT2 probably connects amino acid transport to cellular energy-sensing pathways that control thermogenic capacity.26

EPSTI1 (Epithelial Stromal Interaction 1) is a marker for beige adipocyte precursors induced by the cold and β-adrenergic stimulation before genes like UCP1. It mediates immune-adipose crosstalk during beige adipocyte recruitment, connecting inflammatory signals to adaptive thermogenesis.27,28 This interferon-inducible gene increases during beige adipocyte development but not during white or classical brown adipogenesis.

Additional markers: Tbx1 commits progenitor cells to the beige adipocyte lineage, while Cited1 indicates emerging thermogenic potential.29,30 PDE3A participates in intracellular signaling pathways that control beige adipocyte activation and energy metabolism.31

Nonclassical adipocyte markers are associated with specialized subtypes of fat cells, distinct from the classical adipocytes primarily involved in lipid metabolism. Instead they have roles in immune responses, extracellular matrix deposition, vascularization, and mitochondrial processes. Some non-classical markers include:

By combining findings from IHC, ICC/IF, western blot and transcriptomics, a heat map of exemplar markers across various tissues has been generated, incorporating non-classical markers (Table 2), to assist in finding the optimal markers for your experiments.3

| Category | Marker | Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue (SAT) | Visceral Adipose Tissue (VAT) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA1 Classical | SA2 Angiogenic | SA3 Immune-related | SA4 Immune (adaptive) | SA5 ECM | SA6 Other | SA7 Other | VA1 Classical | VA2 Angiogenic | VA3 Immune-related | VA4 Immune (adaptive) | VA5 ECM | VA6 Mito-ribosomal | VA7 Other | VA8 Other | ||

| White Adipocyte Markers | AQP7 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| PLIN1 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |

| ADIPOQ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |

| LEP | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | +++ | |

| TCF21 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |

| Mitochondrial Marker | MT-CO2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | + | + |

| Nonclassical Adipocyte Markers | PTPRB | - | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| PDE4D | - | - | +++ | ++ | - | - | - | - | - | +++ | ++ | - | - | - | - | |

| SKAP1 | - | - | - | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | +++ | - | - | - | - | |

| ANK2 | - | - | - | - | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | +++ | - | - | - | |

| CD45 | - | - | ++ | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | ++ | +++ | - | - | - | - | |

Table 2: Adipocyte marker expression across adipose tissue subtypes. Expression key: (-) Not expressed (+) Low (++) Medium (+++) High. Based on data from 3

Surveying individual cells has changed how we view fat tissue. Research has discovered unexpected fat cell subtypes in the human belly and under skin fat, each showing unique marker patterns, while new subtypes such as immune-related and ECM-related adipocytes challenge the classical orthodoxy of adipocyte biology.3 These findings highlight the plasticity of adipocytes and their various roles in metabolism, inflammation, and tissue remodeling.3

Mito-Ribosomal Adipocytes (VA6) live in visceral fat. They have increased mitochondrial and ribosomal gene expression, suggesting additional metabolism that may involve enhanced protein synthesis and potentially thermogenic activity.3

Regulatory Adipocytes (RegACs) make resistin and osteopontin. They help control immune responses and are linked to metabolic disorders.32

Lipokine-producing adipocytes (LipoACs) actively transport fatty acid synthases like FADS1/2 (fatty acid desaturases), ELOVL6 (fatty acid elongase), and SCD (stearoyl-CoA desaturase). They create signaling lipids that help regulate metabolism.3

![Anti-Perilipin-1 Antibody [ARC1122] (A306256) - IHC](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/306/A306256_3.jpg?profile=product_image)