Mark F Rosenberg, PhD | 18th March 2025

Fibroblasts coordinate extracellular matrix components (ECM) during tissue development, homeostasis, repair and disease.1 They have variable characteristics, and their function is determined by the surrounding tissue architecture, which supports roles like cell proliferation, ECM secretion, immune cells, and maturation. Fibroblasts have distinct characteristics according to their location within the dermis. Those in the superficial papillary layer are highly proliferative and have loose connective tissue, while fibroblasts in the deeper reticulum make denser collagen.2,3 Fibroblasts are hard to identify despite their abundance because of their heterogeneity and lack of specific markers.4,5

Here, we explore protein markers for identifying fibroblast populations in immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence and flow cytometry experiments.

Fibroblast markers enable researchers to:

Fibroblast markers are important for detecting fibroblast dysregulation, which can contribute to a variety of pathological conditions. For instance, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) play a key role in propagating tumor progression.9,10 Similarly, these markers are indicative of fibrotic diseases, where they highlight the pathological accumulation of the extracellular matrix.11 Fibroblast markers also help identify wound healing disorders, characterized by reduced tissue repair,6 and inflammatory conditions, indicated by altered fibroblast activation.8

PDGFRα (CD140a)

PDGFRα is a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase that coordinates fibroblast proliferation, survival, and migration. Throughout tissue development and repair, PDGFRα facilitates ECM production by PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways. Although PDGFRα is expressed in other mesenchymal cells, this protein is a reliable marker for fibroblast identification in different tissues and its strong expression in fibroblast populations enables its isolation through flow cytometry.12

Vimentin

Vimentin is a type III intermediate filament protein that forms fibroblast structural networks. It keeps cell shape, fixes organelles, and enables fibroblast migration during wound healing. Although again this protein is found in mesenchymal cells, it still allows the detection of fibroblast morphology and behavior using immunofluorescence. Its reliable expression and function in mechanotransduction make it valuable in marker panels.2

Figure 1: Flow cytometry analysis of PDGFR alpha-transfected 3T3 cells stained with Anti-PDGFR alpha Antibody [16A1] (APC) (A85819).

Figure 2: Immunofluorescence of HeLa cells stained with Anti-Vimentin Antibody (A85421) in green, and Anti-Fibrillarin Antibody (A104320) in red. Nuclei are marked with DAPI in blue.

S100A4

S100A4 is an intracellular calcium-binding protein that regulates the cell cycle and differentiation. Single-cell RNA sequencing has shown that S100A4-expressing fibroblasts form a distinct subpopulation in inflammatory conditions like fibrosis and cancer. It was first thought to be fibroblast-specific but is now known to be found in cells involved in inflammation and tissue remodeling. However, S100A4 is useful when combined with additional markers.2,13

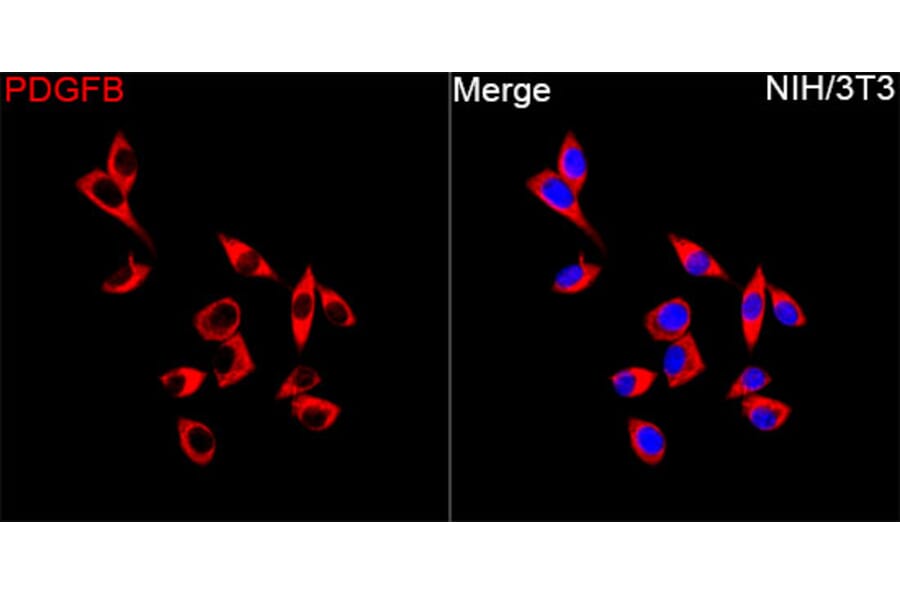

PDGFB

PDGFB is a growth factor, and, in tumors, it promotes fibroblast differentiation into a large population of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs). PDGFB enhances ECM deposition involving a mechanosensitive pathway: it activates myosin light chain phosphorylation, leading to cell contraction and inducing the release of active TGFβ from the ECM. The released TGFβ is involved in further signaling pathways. PDGFB signals by PDGFRα and PDGFRβ receptors facilitating fibroblast expansion—PDGFB loss results in reduced CAF recruitment and ECM deposition, demonstrating its importance in tissue remodeling.14

Figure 3: IHC of human liver tissue stained with Anti-S100A4 Antibody (A306837).

Figure 4: Immunofluorescence of NIH/3T3 cells stained with Anti-PDGF B Antibody (A329725) in red. Nuclei are marked with DAPI in blue.

Single-cell RNA sequencing studies have discovered fibroblast populations with specific marker combinations in human skin.13,15 These populations are found in specific parts of the skin related to their functions.

Papillary Fibroblasts

Papillary fibroblasts contribute to skin homeostasis and regeneration in the superficial dermis under the dermal-epidermal junction.1,16 These cells are responsible for the upper dermis's loose connective tissue, and facilitate wound repair and re-epithelialization.1,2,6,16,17 Their architecture enables them to communicate with both epidermal cells above and reticular fibroblasts in the lower dermal layers.2

These cells house several important markers:

Reticular Fibroblasts

Reticular fibroblasts produce ECM in the lower dermis and can undergo adipogenic differentiation. Transcriptomics studies have shown that they have distinct molecular signatures appropriate to matrix production and organization.2

Reticular fibroblast markers include:

The differential expression of these markers reflects the specialized nature of papillary and reticular fibroblasts in the skin.15 Understanding these molecular differences has revealed how fibroblast populations (secretory-papillary, secretory-reticular, mesenchymal and pro-inflammatory) contribute to skin homeostasis related to the extent of collagen overexpression.11

Quiescent fibroblasts can be activated during injury or disease and are integral to wound healing and tissue repair. However, constant activation can cause cancer. Two important marker proteins help study these fibroblasts:

α-SMA (ACTA2)

Alpha-smooth muscle actin indicates activated myofibroblasts. This protein is not present in quiescent fibroblasts but becomes more expressed during activation.11

FAP (Fibroblast Activation Protein)

FAP is a cell surface protease that is selectively upregulated during tissue remodeling. This protein promotes tumor formation and metastasis by matrix remodeling and influences cancer cell growth. Its expression pattern makes it important for monitoring fibroblast activation in diseased tissue, particularly in cancer.7

Figure 5: IHC of human kidney tissue stained with Recombinant Anti-alpha Smooth Muscle Actin Antibody [RM253] (A121400).

Figure 6: Immunofluorescence of human placenta tissue stained with Anti-Fibroblast Activation Protein alpha Antibody [FAP/4853] (A277595).

No single marker is entirely fibroblast-specific;5 potential influences on the choice of marker include the location in the body,2 the culture environment,8 disease state, and detection sensitivities of different techniques.4,11

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry can identify and isolate fibroblast populations using specific marker combinations. For broad fibroblast detection, PDGFRα+/CD90+ double-positive staining is widely used.19 CD26/CD90 markers can separate papillary from reticular fibroblasts2 and discern specific subpopulations. Activated fibroblasts are well identified using FAP.2

Immunohistochemistry/Immunofluorescence

IHC and ICC/IF provide valuable spatial data about fibroblast distribution and activation inside tissues. Vimentin reveals fibroblast morphology and distribution, while α-SMA specifically distinguishes activated fibroblast populations.5 Parallel to these markers, the ECM protein expression pattern can be monitored to follow cell-matrix interactions. PDGFB production could also be used to follow CAFs.14

Single-Cell Analysis

When analyzing fibroblasts at single-cell resolution, multiple markers could be used to identify populations, providing high specificity for different subtypes and disease states.5,11 For example, recent scRNAseq studies have identified CAF subpopulations, including myofibroblast-like CAFs that express high levels of ECM proteins and inflammatory CAFs with a characteristic cytokine profile.14

![Anti-PDGFR alpha Antibody [16A1] (APC) (A85819) - Flow cytometry](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/85/A85819_249.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Recombinant Anti-alpha Smooth Muscle Actin Antibody [RM253] (A121400) - IHC](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/121/A121400_2.png?profile=product_image)

![Anti-Fibroblast Activation Protein alpha Antibody [FAP/4853] (A277595) - IHC](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/277/A277595_1.jpg?profile=product_image)