Mark F Rosenberg, PhD | 15th April 2025

Cardiomyocytes propagate electrical impulses and mechanical contraction in the heart through a network of structural and regulatory proteins.1 While they occupy 70-85% of heart volume, they represent only 30-40% of heart cell number, with the remainder being fibroblasts, endothelial, and immune cells.2 This diversity of cardiac cell types emphasizes the need for specific markers to identify cardiomyocytes in mixed populations.

Cardiomyocytes form various subtypes with distinct functions. Atrial cardiomyocytes are smaller and have fewer myofibrils, while ventricular cardiomyocytes have a more mature contractile architecture. Specialized cardiomyocytes in the sinoatrial node are pacemaker cells, producing electrical signals for cardiac contraction.3 These different populations express specific marker proteins, which aid their identification and characterization.

Which marker to use for cardiomyocytes depends partially on the cardiomyocyte subpopulation that is being targeted. Table 1 outlines some key cardiomyocyte markers and their differential expression in distinct subsets. These markers, and more, are described in greater detail further down the page.

| Marker | Atrial Cardiomyocytes | Ventricular Cardiomyocytes | Pacemaker Cardiomyocytes | Early/Progenitor Cardiomyocytes | Non-Cardiomyocytes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALCAM (CD166) | * | * | * | +++ | - | 31 |

| ANP | +++ | + | * | * | - | 24 |

| BNP | + | +++ | * | * | - | 24,25 |

| Cardiac Troponins | +++ | +++ | * | * | - | 46 |

| CD34 | - | - | +++ | * | * | 28 |

| Connexin-43 | ++ | +++ | + | * | + | 20,23 |

| HCN4 | + | + | +++ | * | - | 28,29 |

| MYH6 (α-myosin) | +++ | + | * | * | - | 8 |

| MYH7 (β-myosin) | + | +++ | * | * | - | 8 |

| NKX2.5 | +++ | +++ | - | * | - | 28 |

Table 1: Cardiomyocyte marker expression across cellular subtypes. Expression key: (-) Not expressed; (+) Low; (++) Medium; (+++) High; *: Expression level not specifically addressed in the cited references.

Cardiac Troponins (cTnI and cTnT)

Cardiac troponins regulate muscle contraction and relaxation. They are characteristic of mature cardiomyocytes in tissues, as well as being “gold-standard” markers for detecting cardiac damage.4,5 The isoforms, cardiac troponin I (cTnI, encoded by TNNI3) and cardiac troponin T (cTnT, encoded by TNNT2), are cardiomyocyte-specific, differing from their skeletal muscle counterparts. Antibodies for these proteins can detect cardiomyocytes in tissues and cells by IHC and flow cytometry.5

Creatine Kinase-MB (CK-MB)

Creatine Kinase-MB (CK-MB) is located in cardiac muscle and found in the blood after cardiomyocyte damage. This enzyme can track cardiac damage because it appears hours after injury and normalizes within days.6 Although less specific than troponins, CK-MB is a valuable alternative marker for myocardial injury and is often used in parallel to troponins.

Myoglobin

Myoglobin stores oxygen in cardiomyocytes. After cardiac injury, this protein appears in the blood earlier than troponins or CK-MB, making it useful for early detection of myocardial damage.7 However, it is not cardiac-specific as it is also found in skeletal muscle, which limits its use as a cardiomyocyte marker. Myoglobin is, therefore, utilized in a multi-marker approach to quickly assess acute myocardial infarction.

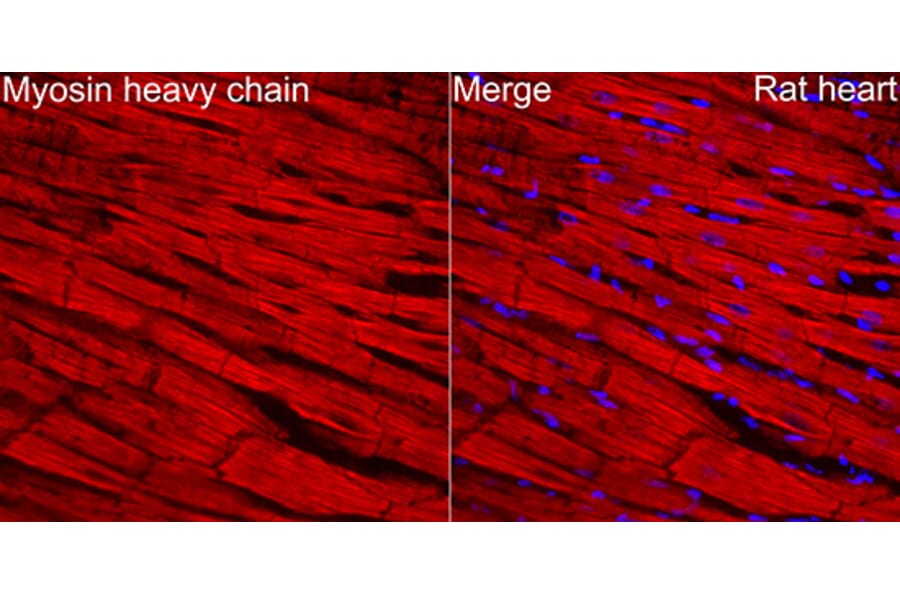

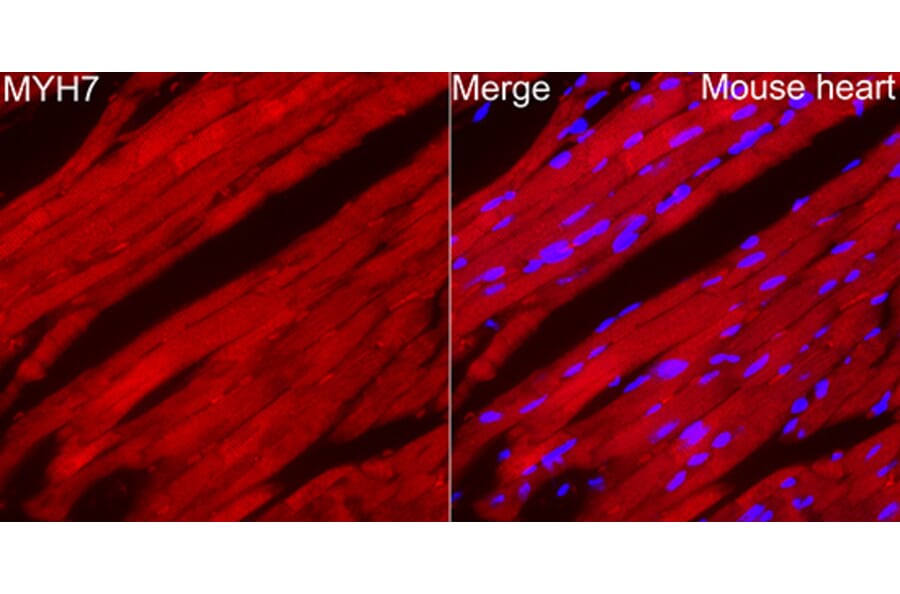

Myosin Heavy Chains (MYH6 and MYH7)

The heart makes two heavy chain myosin isoforms - α-myosin (MYH6) and β-myosin (MYH7). MYH6 predominates in atrial tissue and ventricles under physiological conditions, whereas MYH7 is mainly found in adult ventricles under mechanical stress or disease.8

These two proteins possess distinct contractile characteristics. MYH6 contracts faster than MYH7, and their expression varies during development and disease, enabling the identification of cardiomyocytes and characterizing cardiac conditions. Therefore, antibodies selective for these proteins can distinguish cardiomyocytes in different cardiac chambers and be used to evaluate disease status.

Figure 1: IHC of rat heart tissue stained with Anti-MYH6 Antibody (A329655) in red. Nuclei ar emarked with DAPI in blue.

Figure 2: IHC of mouse heart tissue stained with Anti-MYH7 Antibody (A329656) in red. Nuclei are marked with DAPI in blue.

Sarcomeric α-Actinin

The sarcomeric α-Actinin fixes actin filaments to the Z-disc. This protein-rich structure is inside the heart muscle's sarcomere whilst the α-Actinin engages mechanotransduction inside cardiomyocytes.9 Antibodies for this protein show a cardiac muscle striped pattern, aiding in seeing cardiomyocyte structure by immunofluorescence.

H-FABP

H-FABP (Heart-type Fatty Acid Binding Protein) transports fatty acids and is quickly released during injury. This cytosolic protein can identify cardiomyocytes and detect early myocardial damage.10

Transcription factors regulate cardiac gene expression during development and maturity, typically marking the nuclei of precursor and mature cardiomyocytes.

GATA4, NKX2.5, and TBX5

GATA4 advances heart morphogenesis.11 This zinc finger transcription factor coordinates embryonic cardiac development and cardiomyocyte differentiation, and so can be used to help identify cardio myocyte precursors as well as mature cells. It also protects postnatal cardiomyocytes by activating anti-apoptotic genes.

NKX2.5 (cardiac homeobox protein) regulates gene expression, cooperating with GATA4 and other transcription factors12 – mutations in NKX2.5 elicit congenital heart defects, highlighting its importance in cardiac development. NKX2.5 appears before structural proteins like troponins and identifies cardiomyocyte lineages from early development through adulthood.13 All cardiomyocytes express this marker, making it essential for antibody-based identification.

TBX5 interacts with NKX2.5 and GATA4 to regulate cardiac gene expression and heart chamber formation.12,14 Mutations in TBX5 cause Holt-Oram syndrome, associated with cardiac septal defects and upper limb defects.15

Figure 3: IHC of mouse pancreas stained with Anti-GATA4 Antibody [ARC51718] (A305425).

Figure 4: IHC of human heart tissue stained with Anti-Nkx2.5 Antibody (A83026).

MEF2C and HAND Factors

MEF2C (Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2C) facilitates cardiac myogenesis and morphogenesis.16 This MADS-box transcription factor enables cardiomyoblast differentiation into cardiomyocytes and regulates cardiac contractility and metabolism genes.17 MEF2C expression can be used to mark cardiomyocyte lineage.18

HAND1 and HAND2 (eHAND and dHAND) regulate cardiomyocyte gene expression by interacting with GATA4 and NKX2.5.19 These helix-loop-helix transcription factors assist heart chamber development and cardiac morphogenesis.

Cardiomyocytes also express structural and functional markers, including proteins involved in gap junctions, scaffold proteins, and hormones.

Connexin-43

Connexin-43 forms gap junction channels between cardiomyocytes, enabling small molecule transport, electrical signaling, and contraction.20 This protein is found in the intercalated discs, which also house desmosomes, and facilitates cardioprotection in mitochondrial membranes. Connexin-43 antibodies reveal the three-dimensional architecture of gap junctions and cardiomyocyte connectivity changes during disease.

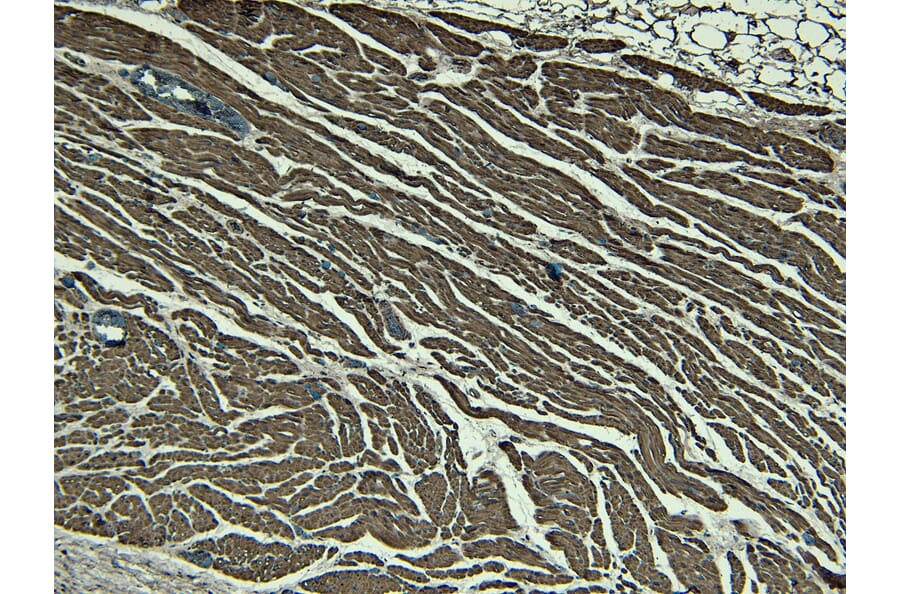

Desmin and Intermediate Filaments

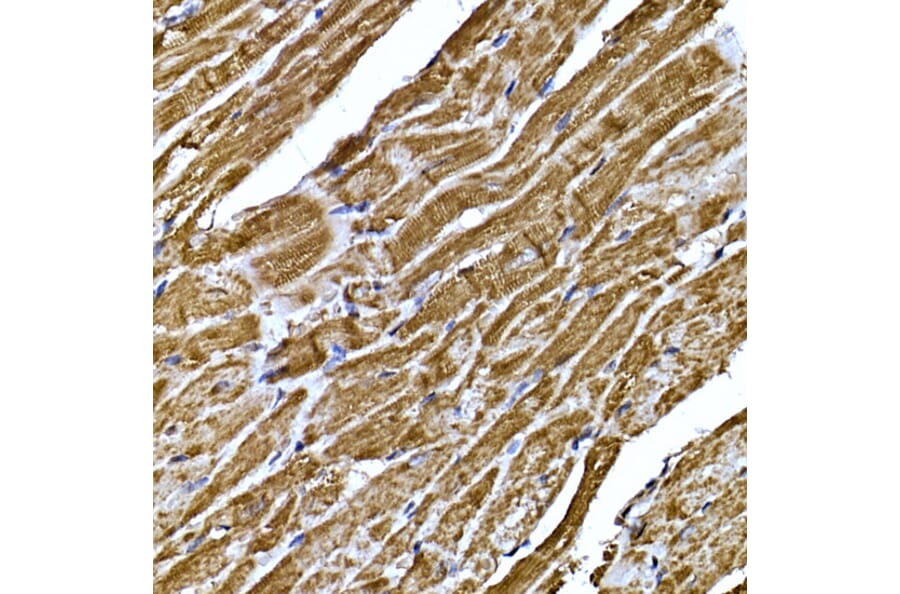

Desmin forms a scaffold around a protein-rich structure called the Z-disc, which surrounds sarcomeres.21 This intermediate filament connects the contractile components to cellular organelles, including the nucleus and mitochondria. Desmin antibodies show cardiomyocyte cytoskeletal architecture, while changes in desmin organization suggest cellular stress or disease.

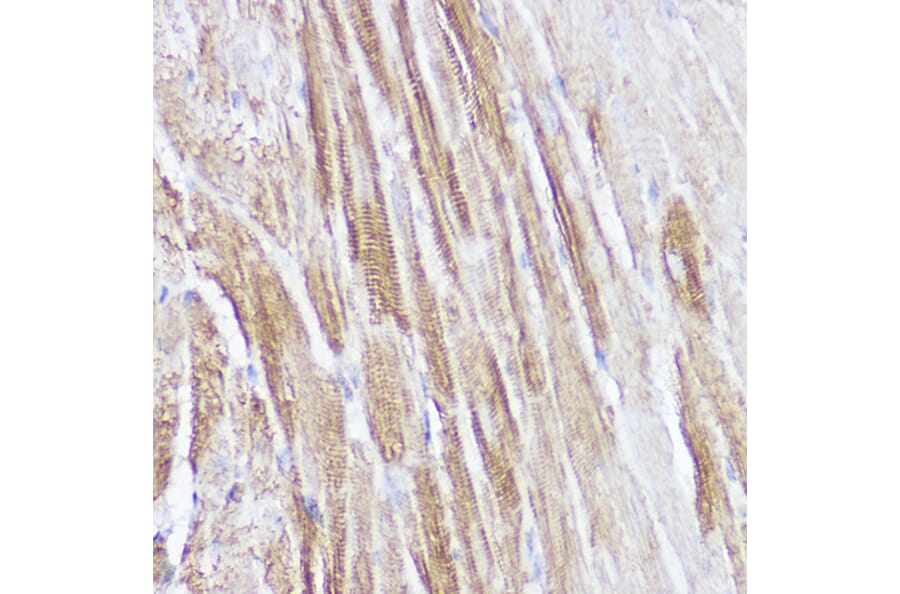

Caveolin-3 and Membrane Structures

Caveolin-3 forms caveolae - small plasma membrane invaginations involved in signal transduction.22 This muscle-specific protein organizes signaling molecules and makes T-tubules for excitation-contraction coupling. Antibodies for caveolin-3 identify cardiomyocyte membrane structures and show changes in cardiomyopathies.

Figure 5: IHC of human heart tissue stained with Recombinant Anti-Desmin Antibody [RM234] (A121399).

Figure 6: IHC of rat heart tissue stained with Anti-Caveolin-3 Antibody [ARC2473] (A307529).

Secreted Peptide Markers

Cardiomyocytes secrete peptides that regulate physiological processes and constitute markers for specific cardiomyocyte populations.23 These factors act in cell signaling mechanisms for cardiovascular homeostasis and disease responses, and are described in Table 2.

| Secreted Peptide | Expression | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Atrial Natriuretic Peptide (ANP) | Atrial cardiomyocytes | Regulates blood pressure, fluid levels, cardiomyocyte growth24 |

| Brain Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) | Ventricular cardiomyocytes | Regulates fluid and sodium levels in urine. Important marker of cardiac stress25 |

| C-type Natriuretic Peptide (CNP) | Mixed cardiomyocytes, as well as endothelial cells and fibroblasts | Controls systemic blood pressure. Prevents myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injuries while improving cardiac remodeling after infarction26 |

Table 2: Peptides secreted from cardiomyocytes

Figure 7: IHC of mouse heart tissue stained with Anti-Natriuretic peptides A Antibody (A88550).

Figure 8: IHC of mouse heart tissue stained with Anti-BNP Antibody (A11515).

Annexin Proteins in Cardiomyocyte Function

These calcium-binding proteins include Annexin A5, which regulates early apoptosis in cardiac disease. This is mainly found in non-myocyte cells within the heart. However, its appearance in the blood can make it useful as a marker for detecting pre-cardiac injury or stress. Annexin A6 (AnxA6) enables heart contractions with less force. Found in most mammalian tissues, including the heart, AnxA6 modulates calcium homeostasis and contractile abilities. Changes in AnxA6 can alter cardiomyocyte calcium processing and contractility, facilitating cardiac dysfunction.27

CD34 is an important marker for core sinoatrial node (SAN) pacemaker cardiomyocytes,28 enabling the identification and purification of pacemaker cells for studying cardiac conduction disorders. Other recently identified markers for this population include:

Figure 9: IHC of mouse fetal heart tissue stained with Anti-Islet 1 Antibody [ARC0511] (A309185).

As well as being present in SANs, HCN4 (Hyperpolarization-activated Cyclic Nucleotide-gated Channel 4) has been found to mark early cardiac lineages.29

Kir2.1

Kir2.1 (Inward Rectifier Potassium Channel 2.1) elicits electrical stability in ventricular cardiomyocytes between contractions and indicates mature ventricular or atrial-functioning cardiomyocytes. This channel establishes the resting membrane potential in live cardiomyocytes but is absent in pacemaker cells.30 This differential expression distinguishes contractile cardiomyocytes from pacemaker cells and is, therefore, a valued marker.

ALCAM (CD166)

ALCAM (Activated Leukocyte Cell Adhesion Molecule, CD166) is a marker used to detect early cardiomyocytes.31 This surface protein mediates cell-cell adhesion and acts in cardiac morphogenesis and tissue development. ALCAM antibodies help isolate early cardiomyocytes in differentiation and assess cardiac progenitor cells.

Chamber-Specific Markers

MLC2a and MLC2v (Atrial and Ventricular Myosin Light Chain 2) show chamber-specific expression.32 MLC2a is found mainly in atrial cardiomyocytes, while MLC2v appears in ventricular cells. These isoforms contribute to the contractile nature of atrial and ventricular muscle. In addition, Pnmt (Phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase) identifies cardiomyocyte subsets, mainly in atrial tissue.33 Traditionally associated with catecholamine synthesis, this enzyme marks a unique cardiomyocyte lineage for cardiac development and function.

N-Cadherin

N-cadherin is a calcium-dependent transmembrane adhesion protein marker for cardiomyocyte progenitors.34 N-cadherin concentrates in the intercalated discs in older cardiomyocytes, facilitating myofibril fixation at cell-cell contacts. The production of N-cadherin distinguishes cardiomyocytes from other cardiac cells and tracks lineage commitment during cardiac differentiation.

Specific markers can track and validate cardiomyocyte differentiation from pluripotent stem cells.35

Differentiation follows a typical expression sequence: early markers, including GATA4, NKX2.5, CD172a, CD106, and TBX5, appear first, followed by contractile proteins like α-actinin and troponins. Functional markers such as connexin-43 and ion channels develop later, indicating mature cardiomyocyte phenotypes.40

In addition to the transcription factors described above, other early markers include SIRPA (Signal Regulatory Protein Alpha, CD172a) and VCAM1 (Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1, CD106).36-39 These cell-surface proteins facilitate cell-cell interactions and can identify cardiomyocyte precursors in mixed progenitor populations during early differentiation.

Growth Factors in Cardiomyocyte Biology

Important cardiomyocyte growth factors include:

Experimental Applications

| Technique | Marker Suggestions | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Flow cytometry | SIRPA/VCAM1 for cardiomyocyte progenitors and cTnT/α-actinin for mature cardiomyocytes | Isolation of cardiomyocytes from mixed populations for downstream applications28,42 |

| IHC and ICC/IF | Alpha-actinin and desmin for sarcomeric structure; connexin-43 for intercellular connections; Transcription factors (e.g. GATA4 and NKX2.5) identify cardiomyocyte nuclei. BNP can also be included for stress response | Cardiomyocyte architecture in cardiac tissue in health and disease43 |

| Single cell RNAseq | Identification of new markers or establishing how known markers change in different states | Revealing cardiomyocyte heterogeneity and correlating markers with location, development and function.44,45 |

Table 3: Cardiomyocyte markers in research

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications

Several cardiomyocyte markers are commonly used in diagnostic and therapeutic applications:

![Anti-GATA4 Antibody [ARC51718] (A305425) - IHC](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/305/A305425_3.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Recombinant Anti-Desmin Antibody [RM234] (A121399) - IHC](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/121/A121399_1.png?profile=product_image)

![Anti-Caveolin-3 Antibody [ARC2473] (A307529) IHC](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/307/A307529_2.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Anti-Islet 1 Antibody [ARC0511] (A309185)) - IHC](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/309/A309185_2.jpg?profile=product_image)