Ryan Hamnett, PhD | 4th February 2025

Cholinergic neurons communicate using acetylcholine (ACh), the first compound proposed as a neurotransmitter in synapses of the central nervous system.1 Cholinergic neurons are diverse in their functional roles, molecular profiles, and associated circuitry (see Cholinergic Neuron Diversity and Functions below).2 Establishing a cell population as cholinergic therefore relies on visualization or detection of ACh itself, or a small number of protein markers that are essential to cholinergic neurotransmission, particularly ChAT, vAChT, and AChE. This guide will cover the primary protein markers of cholinergic neurons that can be detected by techniques such as IHC and ICC/IF.

Marking a cell population as cholinergic enables researchers to:

Decreases in cholinergic neuron numbers, cholinergic neurotransmission or cholinergic markers are associated with cognitive decline in neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease.3,4

Detection of protein markers is generally preferred to direct detection of ACh due to difficulties relating to its rapid hydrolysis and poor fixation, although recent developments in fluorescent reporters mean that observing ACh dynamics is now feasible.5

ACh was first identified as a neurotransmitter in the 1920s,6 and since then a wide range of cholinergic neuron functions have been established across the central and peripheral nervous systems.2

In the brain, cholinergic neurons and are known for fine-tuning brain function and maintaining balance between excitation and inhibition,7,8 which in mammals are primarily mediated by glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons. Cholinergic neurons are distributed throughout the brain, particularly in the striatum, basal forebrain and brainstem, and two main types of cholinergic neuron exist: interneurons and projection neurons. Cholinergic interneurons, such as those in the cortex and the striatum, tend to project locally within a specific brain region. In contrast, cholinergic projection neurons, such as those found in the basal forebrain and brainstem, project over longer distances to other regions of the brain.9

ACh is one of the dominant neurotransmitters in the periphery, mediating transmission from preganglionic and postganglionic neurons in the parasympathetic nervous system, preganglionic neurons in the sympathetic nervous system, and stimulating intestinal contractility in the enteric nervous system.10,11 Motor neurons of the somatic nervous system are all cholinergic, using ACh to directly stimulate muscle activity via muscarinic ACh receptors (mAChRs) at the neuromuscular junction.

The functional diversity of cholinergic neurons is reflected at the cellular and molecular levels: cholinergic neurons can be distinguished from each other by their morphology, localization, developmental origin, transcription factor expression, and electrical activity patterns.2 Given their molecular diversity, only a handful of markers are common across all cholinergic neurons that can be used as protein markers, discussed below.

Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) is the enzyme responsible for synthesizing ACh from choline, a substance taken up from food, and an acetyl group from acetyl Coenzyme A, a product of oxidative metabolism within the mitochondria. ChAT is the most commonly used marker of cholinergic neurons, functioning as a marker even in C. elegans.12

Though ChAT, and therefore ACh biosynthesis, are localized mainly in nerve terminals at synapses, immunohistochemical staining of ChAT can be seen throughout the cytoplasm and cell body.13 ChAT tends to stain peripheral cholinergic neurons more weakly than in the central nervous system, leading to the discovery of a ChAT spliceoform in the peripheral nervous system that misses 4 consecutive exons. This was termed pChAT.14

Figure 1: ChAT expression in the spinal cord. IHC of a mouse spinal cord section showing ChAT-positive motor pools (blue), alongside pan-neuronal marker NeuN (green). Copyright © 2025, Jen Shadrach, PhD.

Vesicular ACh transporter (vAChT) is a protein that uses a proton gradient to transport ACh into synaptic vesicles for storage and subsequent release at the synaptic terminal.15 vAChT is a reliable alternative to ChAT, and it has been noted that vAChT immunostaining can more clearly mark cholinergic axon terminals than ChAT, which can make it the preferred marker when investigating colocalization with other synaptic proteins or with ACh receptors on cholinoceptive terminals.1,16

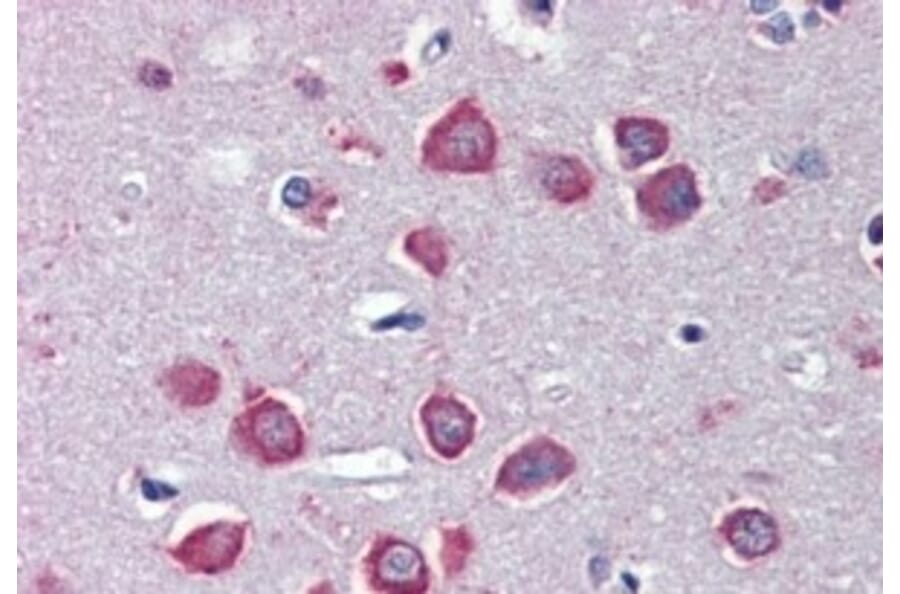

Figure 2: IHC of mouse brain stained with rabbit anti-vAChT (A91949) in red. Nuclei were stained by DAPI in blue.

Figure 3: ICC/IF human neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5Y) stained with mouse anti-vAChT [S6-38] (A305008) in green. Counterstained with Hoechst (blue) and phalloidin (red).

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is an enzyme that breaks down ACh to choline and acetic acid following its release into the synapse, halting cholinergic neurotransmission. While AChE has historically been used as a marker and does genuinely mark cholinergic neurons, the presence of AChE alone cannot confirm cholinergic identity given that cholinoceptive cells also express AChE and AChE can even be released from cells.17 This contrasts to ChAT and vAChT, which are found exclusively in neurons that release ACh. Nonetheless, AChE has been extensively used as an immunohistochemical marker, and its expression indicates cholinergic circuitry.18

Choline transporter 1 (CHT1, encoded by the SLC5A7 gene) is a high affinity transporter of choline, responsible for moving choline into the neuron from the extracellular space for ACh synthesis. This is an essential component in ensuring that neurons have sufficient ACh for neurotransmission, given that choline provision is the rate limiting step in ACh biosynthesis. CHT1 expression and function are dynamic and respond to cholinergic neuron activity and local conditions: CHT1 enables coupling of choline reuptake with neuronal activity by being trafficked to the plasma membrane upon depolarization and synaptic release of ACh.19 CHT1 is even able to compensate in the case of reduced ChAT activity, ensuring normal cholinergic function.20

As a marker of cholinergic neurons, CHT1 is found predominantly in axon terminals and colocalizes well with ChAT and vAChT.21 CHT1 also provides a pharmacological means of manipulating cholinergic neuron activity via the competitive inhibitor hemicholinium-3 (HC3), to which it is highly sensitive.

Cholinergic Receptors

Markers such as ChAT and vAChT are pre-synaptic markers, enabling the identification of cholinergic neurons, but the identification of post-synaptic neurons, or cholinoceptive neurons, can allow the full elucidation of cholinergic circuitry. As well as AChE, key markers of receptive neurons include ACh receptors (AChRs). While these proteins are not ideal as markers because cholinoceptive neurons may express any of a large number of different receptors, the specific receptors present can indicate how ACh will influence the activity of the recipient cell.

AChR receptors are broadly divided into two classes. Ionotropic nicotinic AChRs (nAChRs) are ligand-gated ion channels that can directly depolarize cells, while metabotropic muscarinic AChRs (mAChRs) are G-protein-coupled receptors that modulate the excitability of recipient cells. They are named for their pharmacological sensitivity to nicotine and muscarine, respectively. There are 5 mAChRs (M1-M5), while 17 different subunits have been identified that combine to create functional nAChRs.

AChRs can be found on neurons as well as non-neurons, such as mAChRs on skeletal muscle fibers at the neuromuscular junction. Both classes of AChRs are found widely throughout the brain.22,23

Figure 4: IHC of human cortex stained with goat anti-nAChRα7 (A83507).

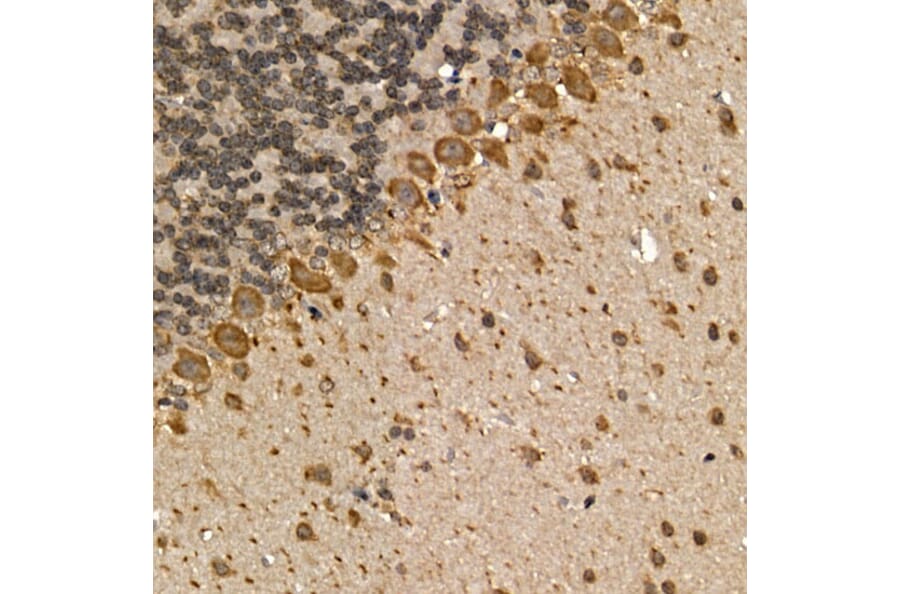

Figure 5: IHC of FFPE mouse brain stained with rabbit anti-mAChR1 (A13536).

Transcription Factors in Cholinergic Neurons

A diverse number of transcription factors are responsible for the fate and development of different cholinergic populations, such as Nkx2.1,24 Lhx8,25 Isl1,26 Fgf8 and Fgf1727. Knocking out these genes results in losses of specific cholinergic neuron subsets. While this means that no single transcription factor can be used to mark all cholinergic neurons, they can be used for more specific cholinergic populations within brain nuclei in particular. Single cell RNAseq studies continue to discover markers in an unbiased fashion, including transcription factors, allowing ever finer resolution of cholinergic subpopulations.28,29

![ICC/IF of SH-SY5Y cells using Anti-VAChT Antibody [S6-38] (A305008)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/305/A305008_3.png?profile=product_image)