Ryan Hamnett, PhD | 20th January 2025

Glutamatergic neurons communicate using glutamate, the most common excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain. Glutamate neurons can be characterized based on their expression of key protein markers, which can be detected using antibodies in techniques such as IHC and ICC/IF. The most established glutamatergic marker proteins are the vesicular glutamate transporter (VGLUT) family proteins VGLUT1 and VGLUT2. Other markers of glutamatergic circuitry include glutaminase, glutamine synthetase, and glutamate receptors such as NMDAR1 and NMDAR2B. This guide will cover the most commonly used glutamatergic neuron markers and illustrate what information they can provide in experiments.

![Immunofluorescence - Anti-NMDAR1 Antibody [ARC0684] (A308794)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/category/primaries/cell-markers/Glutamatergic_IHC_A308794_2_crop.jpg)

Glutamatergic communication is essential for a wide range of neural processes such as synaptic plasticity, learning and memory. Dysregulation of glutamatergic transmission is associated with neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's, as well as conditions such as epilepsy and schizophrenia. Using glutamatergic neuron markers is an ideal method for monitoring of glutamate neuron numbers during disease, and can also:

VGLUT proteins concentrate or load glutamate into synaptic vesicles for exocytotic release at the synapse, and therefore at least one of them is expressed in every glutamatergic neuron. There are three members of the VGLUT family: VGLUT1 (Slc7a7), VGLUT2 (Slc7a6) and VGLUT3 (Slc7a8). All three VGLUTs are multipass membrane proteins, likely with either 12 (VGLUT1 and 2) or 10 (VGLUT3) transmembrane domains.1–3

VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 are reliably expressed in glutamatergic neurons, and are therefore recommended as glutamatergic neuron markers. In contrast, VGLUT3 is often found in non-glutamatergic cell types, and so is not useful as a glutamatergic marker.4

Mouse monoclonal anti-VGluT1 Antibody [S28-9] (A304823) (red). Counterstained with NeuN.

Goat polyclonal anti-VGluT1 Antibody (A326310).

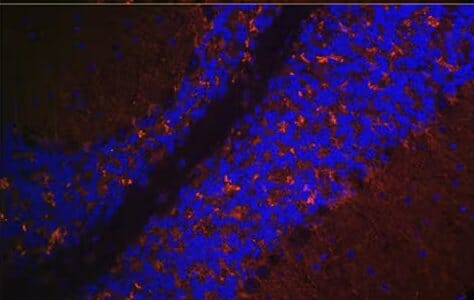

Rabbit polyclonal anti-VGLUT2 Antibody (A90888) (red). Counterstained with DAPI (blue)

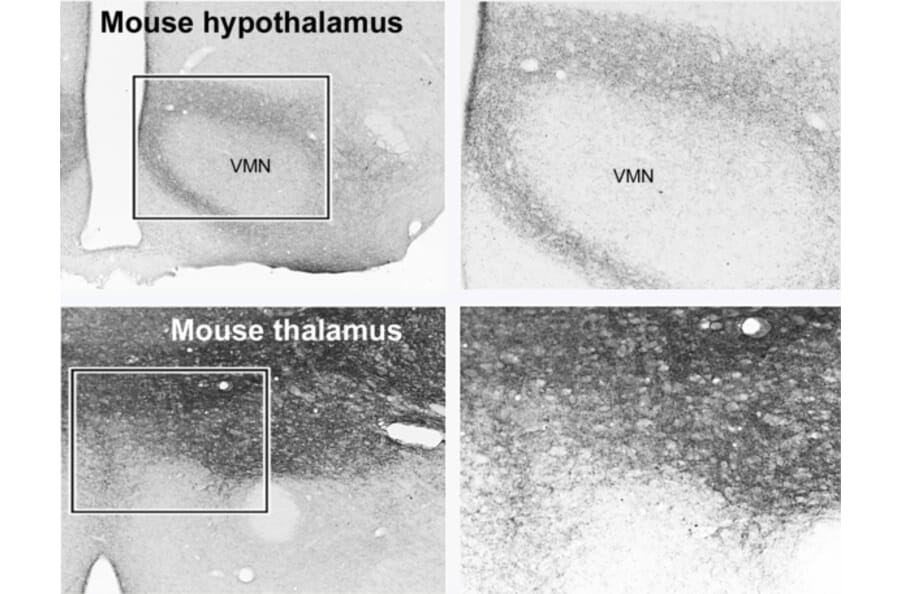

VGLUT Distribution in the Nervous System

Given how prevalent glutamatergic transmission is, VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 are widely expressed throughout the brain, often with complementary expression profiles.5,6 For example, VGLUT1 tends to be strongly expressed in the cerebral cortex, cerebellum and hippocampus, while VGLUT2 is found in the thalamus, hypothalamus and brainstem.5,7 Outside of the brain, VGLUT2 predominates in the spinal cord and enteric nervous system. Co-expression of both VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 is also seen in some cell types, including cerebellar mossy fiber terminals.8

In contrast to the wide distribution of VGLUT1 and 2, VGLUT3 is expressed in sparse neurons in the striatum, hippocampus, cerebral cortex, and raphe nuclei.

Limitations of VGLUT1 and 2 as Markers

While VGLUT1 and 2 are excellent markers of glutamatergic neurons, there are some limitations to their use.

Firstly, both VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 must be used to reliably mark all glutamatergic neurons. A protein of interest failing to colocalize with VGLUT1 could still be expressed in VGLUT2+ glutamatergic neurons.

Secondly, both VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 are localized at synapses, meaning they do not usually mark the cell body (soma) of glutamatergic neurons. While this makes them ideal for colocalizing with other pre-synaptic proteins, such as synapsin, or demonstrating close apposition with post-synaptic proteins, such as glutamate receptors, they will not colocalize with proteins restricted to the soma by immunofluorescence. One way around this is to instead stain for Vglut1 and Vglut2 mRNA with in situ hybridization, which is usually found in the cell body. Another is to use fluorescent reporter lines that will reflect VGLUT1 or VGLUT2 expression, such as using Cre recombinase (e.g. VGLUT2-Cre) and a Cre-dependent reporter.

Glutaminase and glutamine synthetase

While the biosynthesis of glutamate can be achieved in several ways, including from metabolic intermediates such as α-ketoglutarate, one of the most important in neurons is to generate it from glutamine, another common amino acid. The glutamate-glutamine cycle occurs between astrocytes and neurons (Figure 1): neurons release glutamate at synapses, which is mopped up by astrocytes. Astrocytes convert this glutamate to glutamine and return it to neurons, which convert it back to glutamate for synaptic loading.9

Figure 1: Glutamate-glutamine cycle. Glutamate is released at the synapse from VGLUT-loaded vesicles to bind to glutamate receptors. Other glutamate transporters, such as excitatory amino acid transporters (EAAT) recycle excess glutamate. In astrocytes, this is converted to glutamine and returned to neurons by amino acid transporters such as SN1 and SAT2. Diagram created with BioRender.

Enzymes that are involved in the glutamate-glutamine cycle can therefore be used as markers of glutamatergic neurons. Glutaminase, the enzyme in neurons that catalyzes the deamination of glutamine into glutamate, is most commonly used. The limitation for using glutaminase as a marker is that glutamate is used in non-glutamatergic neurons as a fuel source and precursor to other metabolites, such as GABA,10 meaning the presence of glutaminase does not guarantee that a neuron is glutamatergic.

Glutamine synthetase is the corresponding enzyme in the cycle, catalyzing amination of glutamate to glutamine. Glutamine synthetase is therefore mainly a marker for astrocytes associated with glutamatergic synapses, rather than glutamate neurons themselves, although neurons may begin to express it in neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.11–13

Rabbit polyclonal anti-Glutaminase Antibody (A11694) (red). Counterstained with DAPI (blue).

Rabbit polyclonal anti-Glutamine Synthetase Antibody (A307948) (red). Counterstained with DAPI (blue)

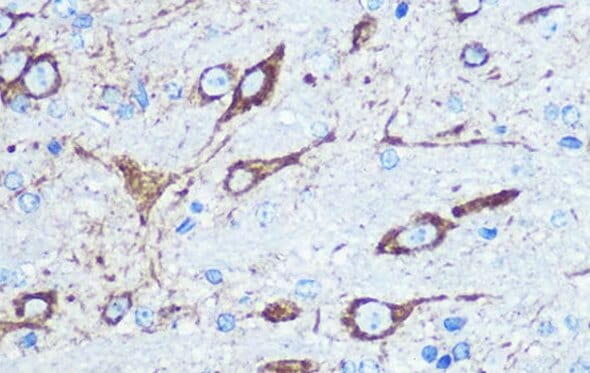

Rabbit polyclonal anti-NMDAR1 Antibody (A15836).

Glutamate Receptors

There are a plethora of glutamate receptors expressed throughout the nervous system, divided into 2 types: ionotropic receptors, which are ligand-gated ion channels, and metabotropic receptors, which have multiple transmembrane domains and tend to be more neuromodulatory in nature. Within each of these classifications, there are further subdivisions, such as NMDA, AMPA and kainate ionotropic receptors, named for pharmacological activators. In total there are 24 genes for glutamate receptors or receptor subunits.

Glutamate receptors can therefore be used to mark glutamate-receptive neurons. For example, NMDAR1 is a subunit that is essential for a functional NMDA receptor, and so will be found on almost all post-synaptic sites that receive glutamate input.

![IHC of mouse spinal cord using Anti-VGluT1 Antibody [S28-9] (A304823)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/category/primaries/cell-markers/Glutamatergic_IHC_A304823_3_crop.jpg)