Ryan Hamnett, PhD | 10th September 2024

The structure that DNA takes in the nucleus strongly influences numerous cellular processes, including gene expression, the DNA damage response, and cell division. This structure is primarily determined by histones. Histones are proteins that DNA wraps around to form chromatin, and they can be modified with epigenetic marks to dictate how loose or compact that DNA-histone interaction is. Histone modifications are tightly regulated and can respond to cellular stimuli and external cues as a dynamic method of controlling transcriptional activity.

This guide covers the basics of histone proteins, how histones are modified, and the consequences of those modifications, as well as techniques that researchers can use to study histone proteins.

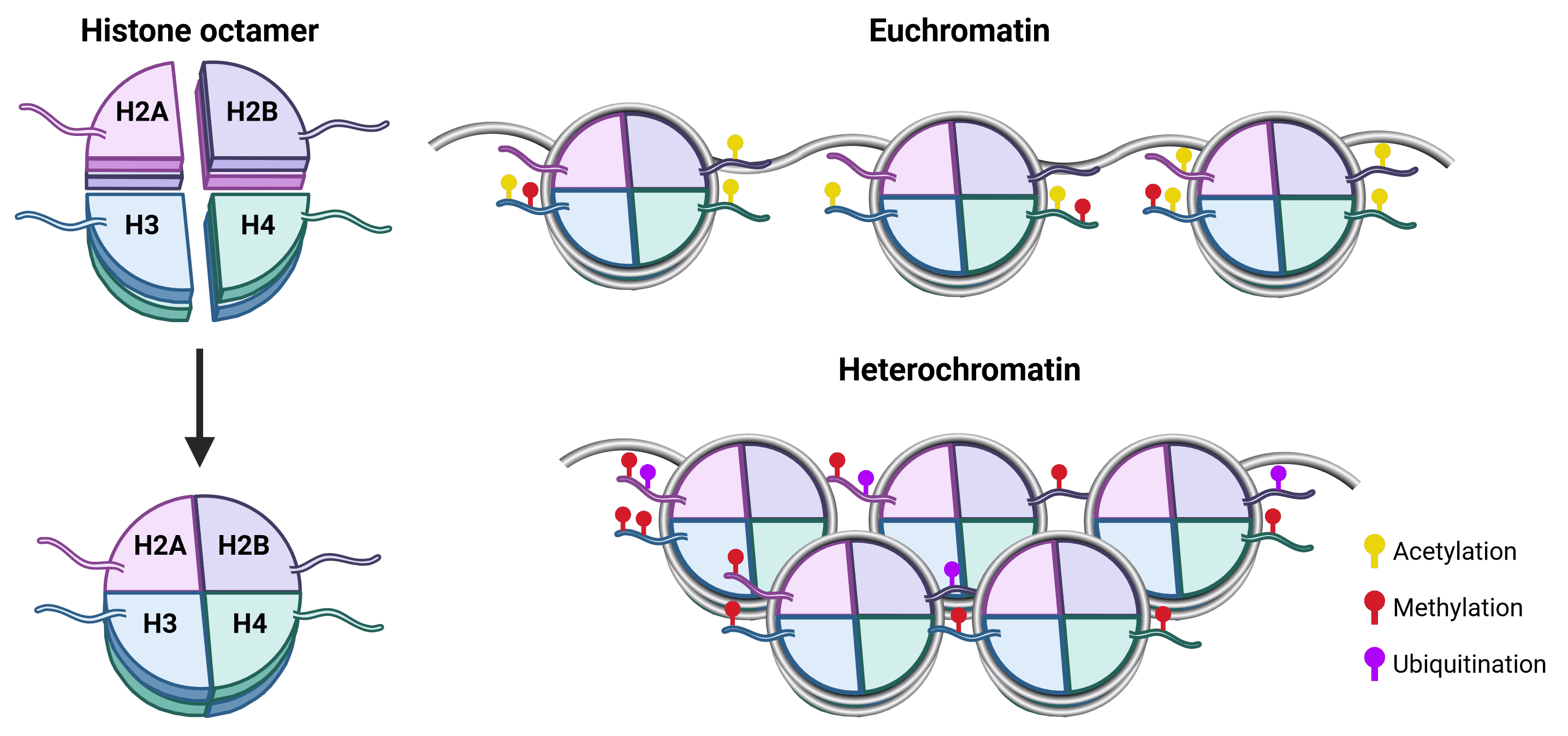

DNA in the nucleus exists as chromatin, which refers to DNA in a complex with evolutionarily conserved proteins called histones. The resulting DNA-protein complex is termed a nucleosome. Nucleosomes are the fundamental building block of chromatin, with nucleosomes strung on DNA like beads on a string then further packaged and coiled into higher order chromatin structures (Figure 1).

Figure 1: DNA complexes with histone proteins to form chromatin. Chromatin forms higher order structures to facilitate packaging in the nucleus.

The structure of chromatin facilitates the careful spatial organization of an organism’s genomic material in the nucleus, which is essential for transcriptional regulation, packaging DNA into a small volume to fit in nuclei, and protecting the DNA sequence from disruption. Chromatin structure also influences DNA replication, mitosis and meiosis, DNA repair and genetic recombination.

Histone Protein Expression

The transcription and translation of histone proteins themselves are tightly regulated, because excess accumulation of histones results in genomic instability, DNA damage, chromosome aggregation or loss, and cell death.1 Core histone genes have an unusual structure at both the DNA and RNA levels: the genes are found clustered together, do not contain introns and their RNA is not poly-adenylated.2

The core histone proteins are incorporated into chromatin during DNA replication in S phase of the cell cycle, which is why they are often referred to as replication-dependent histones.3 This deposition of histones is managed by histone chaperone proteins working alongside DNA polymerase;4 these chaperones, like histone mRNA, tend to be abundant only during S phase.

Nucleosome Structure

There are 5 different histone proteins (plus some variants5): H1, H2A, H2B, H3, H4. Two copies each of H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 bind together to form a histone core, around which 147 bp of DNA wraps 1.75 times (Figure 2). While H1 is not in the core nucleosome, it acts as a linker protein and is important for stabilizing DNA-histone interactions and the assembly of higher order chromatin.6

Figure 2: Nucleosome composition and chromatin architecture.The core histone octamer of the nucleosome is formed of an H3-H4 tetramer and two H2A-H2B dimers. Each histone protein has an unstructured N-terminal tail (as well as an unstructured C-terminal for H2A) that protrudes from the nucleosome core and are accessible to histone-modifying proteins. This makes histone tails, particularly of H3 and H4, the main site for posttranslational modifications (PTMs), which in turn influence chromatin state and can recruit transcription factors via reader proteins. Transcriptionally active euchromatin is marked by acetylation, while methylation can be associated with either euchromatin or heterochromatin depending on the methylated residue. Ubiquitination is also associated with transcriptional silencing, and tends to occur on residues of H2A and H2B.7

Chromatin State

Chromatin exists in two main states (Figure 2). Euchromatin is loosely packed, which makes it accessible to transcription machinery such as RNA polymerase complexes, as well as transcription factors and cofactors. It is therefore more permissive of gene transcription.8 In contrast, heterochromatin is tightly packed, preventing binding of transcription factors and so associated with reduced transcription. As well as providing a method for gene silencing, heterochromatin is also thought to be important for the maintenance of genomic stability.9

There are 4 core mechanisms of regulating the chromatin state that work in concert to control DNA accessibility and gene transcription:10

Histone Variants

There are several histone protein variants that perform specific functions, respond to defined stimuli, or are present in certain tissues such as the gametes. Some histone variants differ in residue identity by as much as 50% from their core histone counterpart, while others differ by only a few amino acids, but biophysical analyses indicate that even a few amino acid differences can substantially alter the DNA-protein interface.11,12 Substituting specific histone variants into the nucleosome can therefore alter the nucleosome structure and its interaction with DNA, resulting in changes to chromatin and higher order chromatin architecture. In this way, they represent an important tool in transcriptional regulation and have distinct functions in cell division, DNA repair, and differentiation.5

Some histone variants, such as the essential H3 variant H3.3, are found ubiquitously throughout the body, others are located within specific types of chromatin or DNA, such as CENP-A at the centromere, but many are specific to the DNA packaging requirements of gametes. Table 1 illustrates many of the histone variants found in mammals, where they are found in the body, and unique features of their function or expression.

| Canonical Histone | Histone Variant | Function and Features |

|---|---|---|

| H2A | H2A.X | Distributed throughout the genome, accumulates at sites of DNA damage to recruit DNA repair proteins. DNA repair, remodeling sex chromosomes |

| H2A.Z.1 | Transcriptional regulation, transcription initiation heterochromatin organization, chromosome segregation, genome stability, cellular proliferation | |

| H2A.Z.2 | Transcriptional regulation | |

| macroH2A | Restricted to vertebrates. Enriched in transcriptionally silenced regions of the genome. Suppresses transcription by inhibiting recruitment of transcription machinery and chromatin remodelers. | |

| H2A.J | Conserved in mammals. Accumulates in senescent cells and upregulates inflammatory gene pathways | |

| H2A.Bbd (H2A.B) | Short H2A variant. Restricted to vertebrates. Found in high levels in testis and brain. Increases transcriptional activity by reducing chromatin compaction. | |

| H2A.L.2 | Short H2A variant. Facilitates histone-to-protamine transition during spermatogenesis | |

| H2A.P, H2A.Q | Short H2A variants. Found in the testis | |

| TH2A (H2A.1) | Found in the gametes, where it dimerizes with TH2B. Enhances reprogramming to pluripotent state. | |

| H2B | TH2B (H2B.1) | Found in the gametes, where it dimerizes with TH2A. Enhances reprogramming to pluripotent state. |

| H2B.E | Found in odour-sensing neurons of mice, associated with cell longevity | |

| H2B.K | Found in ovaries, oocytes and zygotes | |

| H2B.L | Not found in chromatin; localizes to the subacrosome in sperm | |

| H2B.N | Found in ovaries, oocytes and zygotes | |

| H2B.W | Testis-specific, localized to telomeres | |

| H2B.3 | Enriched in mature leaves and in nucleosomes containing H3.3 and/or H2A.Z | |

| H3 | H3.3 | Found at both active and silenced regions, mediated by distinct chaperones. Nucleosomes containing H3.3 are deposited at sites that have lost nucleosomes during transcription: active genes, promoters, etc. Also found at telomeres, imprinted genes and heterochromatin to maintain heterochromatin state. |

| H3T (H3.4) | Found in testis, and developing spermatozoa. Essential for spermatogenesis, ensures entry into meiosis, granting an open chromatin state. | |

| H3.5 | Found in testis in immature gametes, seminiferous tubules. Associated with actively transcribed regions | |

| H3.6 | Weakly expressed in various tissues, forms unstable nucleosomes | |

| H3.7 | Weakly expressed in various tissues, forms unstable nucleosomes | |

| H3.8 | Weakly expressed in various tissues, forms unstable nucleosomes | |

| H3.X | Primate-specific. Accumulates at transcriptional start sites of actively transcribed genes, open chromatin state. | |

| H3.Y | Primate-specific. Accumulates at transcriptional start sites and coding region of actively transcribed genes, open chromatin state. H3.Y nucleosomes tend to exclude H1. | |

| CENP-A (CenH3) | Indicates centromere location, required for kinetochore attachment and chromosome segregation during mitosis | |

| H3mm6-18 | Mouse specific H3.3 variants. H3mm7 is expressed in skeletal muscle satellite cells. Some form stable nucleosomes, while others are more labile. | |

| H4 | H4.7 (H4.G) | Found in nucleolus. Produces less compact chromatin on ribosomal DNA, promoting rDNA transcription |

| H1 | H1.0 | Enriched in nucleolus. May replace H1 in terminally differentiated cells. |

| H1.1 | Widely expressed, peaks in S phase. | |

| H1.2 | Widely expressed, peaks in S phase. Important for chromatin compaction | |

| H1.3 | Widely expressed, peaks in S phase. | |

| H1.4 | Widely expressed, peaks in S phase. | |

| H1.5 | Widely expressed, peaks in S phase. | |

| H1.6 | Found in testis | |

| H1.7 (H1T2) | Found in testis | |

| H1.8 (H1oo) | Enriched in oocytes. | |

| H1.9 (HILS1) | Found in testis | |

| H1.10 (H1X) | Enriched in nucleolus |

Table 1:Histone variants and their tissue expression and associated functions. Information sourced from references 5,11,13–17.

Histone Variant Regulation

Histone variants are not variants in the sense of splice isoforms. Instead they are separate genes, located outside of the replication-dependent histone gene clusters. While some variants, such as some H1 variants, are regulated in a similar manner to the core histones, the transcriptional and translational regulation of most variants is more typical of other genes in the genome. Their mRNA is poly-adenylated, expression is not tied to the cell cycle, and their genes contain introns, making alternative splicing a possibility for some variant genes.

Distinct chaperones tend to be involved in depositing and removing histone variants compared to the core histone proteins, and the identity of those chaperones can determine the role of the variant in gene regulation. For instance, H3.3 is incorporated into active genes by the chaperone Hira, but deposited into heterochromatin and telomeres by the chaperone dimer Atrx/Daxx.5

Posttranslational Modifications of Histones

While histone variants represent one way to modify chromatin state, a more common, faster and more responsive approach is to modify the core histone proteins that are already present within nucleosomes. Posttranslational modifications (PTMs), particularly of lysine residues, are major determinants of chromatin state by influencing how tightly packed together nucleosomes are. PTMs typically occur on residues of N-terminal histone tails and include phosphorylation, methylation, acetylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, ADP ribosylation and more.

Some PTMs are strongly associated with one type of chromatin state, for example acetylation of histone tails typically results in euchromatin. Other PTMs, such as methylation, are more context dependent, with the resultant chromatin state being determined by the specific amino acids in the histones that are modified, and the combination of PTMs on neighboring histones.

Histones are modified by specific enzymes known as writers and erasers, and interpreted by proteins known as readers, which can recruit transcription factors and chromatin remodeling proteins.18 Readers, writers and erasers therefore directly influence chromatin state and transcriptional activity at specific genomic loci through their addition, removal and recognition of histone PTMs.19

Histones and Epigenetics

The “histone code hypothesis” posits that histone modifications are the driving force behind transcriptional regulation, with specific combinations of PTMs conferring specific biological functions to the associated region of the genome.

Through histone PTMs, an organism’s phenotype can change without changes to the underlying genetic sequence, leading to histone PTMs being referred to as epigenetic marks. Epigenetics refers to heritable alterations to chromatin that regulate gene expression but do not alter the base sequence of DNA. Methods of transcriptional regulation such as DNA methylation, chromatin remodeling, and non-coding RNA signaling are also considered epigenetic. Epigenetic marks can be influenced by the environment, allowing for dynamic alterations to gene expression that can be passed on to subsequent generations.

Not all histone modifications are epigenetic marks. Histone modifications are often highly dynamic, with acetylation and phosphorylation events appearing and disappearing on chromatin in response to a stimulus within minutes.20,21 For PTMs to be heritable, they must be stable.22 Histone methylation has a much longer half-life and so is more likely to be passed on during cell division.23

Different histone modifications confer different biological functions to regions of DNA, such as making it more or less transcriptionally active, or being involved in specific cellular processes. Acetylation, methylation and phosphorylation are the best understood histone PTMs, but there are now at least 18 histone modifications known, and our knowledge of how they are involved in cellular function continues to expand.24

Figure 3 illustrates the diversity of histone modifications possible on the core histone proteins and the linker H1. Descriptions of the main types of histone modification can be found below, along with tables of their commonly associated biological functions. For a more comprehensive list, we recommend the review by Zhao and Garcia, 2015.24

Figure 3: Schematic of histone modifications sites on the four core histone proteins and the linker H1. Note that histone variants such as H2A.X, H3.3 and CENP-A may have distinct and unique modifications. Distance between amino acid residues is not to scale.

Naming Conventions

A system for naming histone modifications has been devised to enable researchers to describe them with high precision. This is necessary due the number of different histone modifications that there are (and continue to be discovered), and the importance of the identities of both the histone protein and the modified residue. Note that this is not the “histone code” that you might have heard about (see Histones and Epigenetics)! There are 4 components of this convention; we shall use trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27, or H3K27me3, as an example.

| Modification | Abbreviation | Residues |

|---|---|---|

| 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation | hib | K |

| Acetylation | ac | K, sometimes S, T, Y |

| ADP-ribosylation | ar(n) | K, E |

| Biotinylation | bio | K |

| Butyrlyation | bu(t) | K |

| Citrullination (deimination) | cit | R |

| Crotonylation | cr | K |

| Formylation | fo(r) | K |

| Glutathionylation | gt | C |

| Hydroxylation | oh | Y |

| Malonylation | ma | K |

| Methylation | me1, me2, me3 | K, R, sometimes Q, G |

| O-GlcNAcylation | og | K, S, T, Y |

| Phosphorylation | ph | S, T, Y |

| Proline isomerization | iso | P |

| Proprionylation | pr | K |

| Succinylation | suc | K |

| SUMOylation | su | K |

| Ubiquitination | ub | K |

Table 2:Different types of histone modifications. For more information see references 24–26.

Acetylation

Acetylation occurs on lysine residues in all of the core histone proteins, as well as histone H1.27,28 A highly dynamic process, acetylation can appear or disappear in response to a stimulus within minutes.29 Acetyl groups are transferred to the ε-amino group of lysine side chains by histone acetyltransferases (HATs; see Histone Modifying Enzymes – HATs and HDACs), which use acetyl CoA as a cofactor.19 This transfer effectively neutralizes the positive charge that lysine naturally carries, resulting in a weakened interaction between the positively charged histones and negatively charged DNA.

Acetylation of histones is therefore associated with loosely packed euchromatin and increased transcriptional activity. Acetylation of lys9 and lys27 on histone H3 (H3K9ac and H3K27ac) are canonical, strong active marks, frequently associated with active gene promoter and enhancer regions of the genome.

While acetylation may also occur at non-lysine residues, including serine and threonine (e.g. H3T22ac), the role of these modifications in chromatin structure and function is currently unknown.30

| Histone | Site | Histone-modifying Enzyme(s) | Proposed Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2A | Lys5 | Tip60, p300/CBP | Transcriptional activation |

| H2B | Lys5 | p300, ATF2 | Transcriptional activation |

| Lys12 | p300/CBP, ATF2 | Transcriptional activation | |

| Lys15 | p300/CBP, ATF2 | Transcriptional activation | |

| Lys20 | p300 | Transcriptional activation | |

| H3 | Lys9 | Unknown | Histone deposition |

| Gcn5, SRC-1 | Transcriptional activation | ||

| Lys14 | Unknown | Histone deposition | |

| Gcn5, PCAF, Esa1, Tip60, SRC-1, p300 | Transcriptional activation | ||

| Elp3, Sas3 | Transcriptional elongation | ||

| Esa1, Tip60 | DNA repair | ||

| hTFIIIC90 | RNA polymerase III transcription | ||

| TAF1 | RNA polymerase II transcription | ||

| Sas2 | Euchromatin | ||

| Lys18 | Gcn5 | Transcriptional activation, DNA repair | |

| p300/CBP | DNA replication, transcriptional activation | ||

| Lys23 | Unknown | Histone deposition | |

| Gcn5 | Transcriptional activation, DNA repair | ||

| p300/CBP | Transcriptional activation | ||

| Sas3 | Transcriptional elongation | ||

| Lys27 | p300/CBP, Gcn5 | Enhancer function, gene expression | |

| Lys36 | Gcn5 | Marker of active promoters | |

| Lys64 | p300 | Nucleosome dynamics and transcription | |

| H4 | Lys5 | Hat1 | Histone deposition |

| ATF2, p300 | Transcriptional activation | ||

| Esa1, Tip60 | DNA repair | ||

| Lys8 | Gcn5, PCAF, Esa1, Tip60, ATF2, p300 | Transcriptional activation | |

| Elp3 | Transcriptional elongation | ||

| Esa1, Tip60 | DNA repair | ||

| Lys12 | Hat1 | Histone deposition, telomeric silencing | |

| Esa1, Tip60, p300 | Transcriptional activation | ||

| Esa1, Tip60 | DNA repair | ||

| Lys16 | Gcn15, Esa1, Tip60, ATF2 | Transcriptional activation | |

| Esa1, Tip60 | DNA repair | ||

| Sas2 | Euchromatin |

Table 3:Acetylation of histones

Methylation

Methylation primarily occurs on lysine and arginine residues of histones H3 and H4, though methylation of H1, H2A, H2B and various histone variants have been observed, including on glutamine and glycine residues.24,31–33 The overall effects of methylation can result in either increased or decreased transcriptional activity, depending on the specific modifications and the context in which they occur.

Unlike acetylation, methylation of histones does not alter DNA-histone interactions by modifying charge, which may explain its more diverse effects compared to acetylation. Instead, histone methylation acts as recruitment sites for chromatin remodeling proteins, such as those containing chromodomains (see Histone Modification Readers). These remodeling proteins modify chromatin state to be more open (euchromatin) or closed (heterochromatin), depending on the context and the specific epigenetic mark. Methylation can also render histones bulkier and more hydrophobic, affecting nucleosome stability and how tightly DNA is wound around histones.

Multi-methylation

To further complicate the landscape of histone methylation, residues can be methylated to different extents. Lysines can be mono-, di-, or tri-methylated, while arginines can be monomethylated and asymmetrically or symmetrically demethylated.

The extent of methylation has important functional consequences. For example, monomethylation of H3K27, H3K9 and H3K79 are associated with gene activation, whereas trimethylation of those residues is linked to gene repression.34 Different amounts of methylation on a given residue may indicate the same effect on transcriptional activity, but mark different genetic elements. For instance, H3K4 methylation marks active genes, but H3K4me1 typically marks transcriptional enhancers, while H3K4me3 marks gene promoters.

Methylation of H3K9 and H3K27

Some of the best-studied histone modifications are those on H3K9 and H3K27. As mentioned above, acetylation of these marks active genes, whereas trimethylation of these same residues (H3K9me3 and H3K27me3) is a well-established signal for gene silencing. These repressive marks contain further nuanced functions. H3K27me3 tends to be a temporary signal in promoter regions, whereas H3K9me3 is a permanent mark in gene-poor genomic regions of heterochromatin, such as satellite repeat regions, telomeres, and certain transposable elements.

| Histone | Site | Histone-modifying Enzyme(s) | Proposed Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Lys26 | Ezh2 | Transcriptional silencing |

| H2A | Arg3 | PRMT1/6, PRMT5/7 | Transcriptional activation, transcriptional repression |

| Gln104 | Fibrillarin | Ribosomal gene expression | |

| H3 | Arg2 | PRMT5, PRMT6 | Transcriptional repression |

| Lys4 | SETD1A/B, MLL, ALL-1 | Transcriptional activation | |

| MLL3/4 | Enhancer function | ||

| Meisetz | Meiotic prophase progression | ||

| Arg8 | PRMT5 | Transcriptional repression | |

| Lys9 | Suv39h, Clr4 | Transcriptional silencing | |

| G9a | Transcriptional repression, genomic imprinting | ||

| SETDB1 | Transcriptional repression | ||

| Arg17 | CARM1 | Transcriptional activation | |

| Arg26 | CARM1 | Transcriptional activation | |

| Lys27 | Ezh2 | Transcriptional silencing, X inactivation | |

| G9a | Transcriptional silencing | ||

| Lys36 | Set2 | Transcriptional elongation | |

| Arg42 | CARM1 | Transcriptional activation | |

| Lys79 | Dot1 | Euchromatin, transcriptional elongation | |

| H4 | Arg3 | PRMT1/5/6/7 | Transcriptional activation |

| Lys8 | SET5 | Stress response | |

| Lys20 | SETD8, PR-Set7 | Transcriptional silencing, mitotic condensation | |

| Suv4-20h | Heterochromatin |

Table 4:Methylation of histones

Phosphorylation

Serine, threonine and tyrosine residues are phosphorylated in all of the core histone proteins and many variants, and are associated with many cellular processes including transcription regulation, DNA repair, mitosis and apoptosis.10 Histone phosphorylation primarily alters gene activity and chromatin structure by recruiting proteins to sites of interest, including chromatin remodeling proteins and writers or erasers of other histone modifications, introducing substantial crosstalk between modifications.

Phosphorylation in the DNA Damage Response

One of the best characterized cases of phosphorylation is the phosphorylation of H2A.X (or H2A in yeast), which plays a major role in the DNA damage response. Following a double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA, phosphorylation of H2AS129 near to the DSB occurs within 30 minutes.10 This modification then spreads over several kilobases or even megabases up- and down-stream of the DSB, creating a clear platform to recruit DNA repair proteins. One of these is the NuA4 acetyltransferase complex, leading to acetylation of histone H4 and an open chromatin state to facilitate DNA repair.

Phosphorylation in Transcription Regulation

Phosphorylation of histone H3S10, H3S28 and H2BS32 have all been associated with regulating gene activity, particularly for proliferation-related genes, such as in response to epidermal growth factor (EGF)-responsive genes, and the proto-oncogenes c-fos, c-jun and c-myc.

Phosphorylation is often linked with acetylation in the regulation of genes. For example, phosphorylation of H3S10, T11 and S28 result in Gcn5-dependent acetylation of H3.10 Similarly, in cells that have been stimulated with EGF, H3S10ph is strongly associated with H3K9 and H3K14 acetylation, which are indicators of gene activity. Interactions between phosphorylation have also been shown, such as H3S28ph resulting in demethylation of the neighboring H3K27, relieving the gene silencing imparted by that mark.

Phosphorylation in Chromatin Compaction

Histone phosphorylation is also involved in chromatin compaction and chromatid separation that are necessary for mitosis and meiosis, for which histone H3 residues T3, S10, T11, and S28 are known to be important.10

Chromatin condensation also occurs during apoptosis. H2BS14ph is important for this, again acting as a platform for acetylation of a nearby lysine residue. H2A.X phosphorylation also increases upon DNA fragmentation and apoptosis, with H2AXY142 appearing to recruit pro-apoptotic factor JNK1 instead of repair factors.10

| Histone | Site | Histone-modifying Enzyme(s) | Proposed Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Thr10 | Unknown | Mitosis |

| Ser17 | Unknown | Mitosis (interphase) | |

| Ser27 | Unknown | Transcriptional activation, chromatin decondensation | |

| Thr137 | Unknown | Mitosis | |

| Thr154 | Unknown | Mitosis | |

| Ser172 | Unknown | Mitosis (interphase) | |

| Ser188 | Unknown | Mitosis (interphase) | |

| H2A | Ser1 | Unknown | Mitosis, chromatin assembly |

| MSK1 | Transcriptional repression | ||

| Thr120 | Bub1, VprBP | Mitosis, transcriptional repression | |

| Ser139 (H2A.X) | ATR, ATM, DNA-PK | DNA repair | |

| Thr142 (H2A.X) | WSTF | Apoptosis, DNA repair | |

| H2B | Ser14 | Mst1 | Apoptosis |

| Unknown | DNA repair | ||

| Ser36 | AMPK | Transcriptional activation | |

| H3 | Thr3 | Haspin/Gsg2 | Centromere mitotic spindle function |

| Thr6 | PKCβ | Inhibits AR-dependent transcription | |

| Ser10 | Aurora-B kinase | Mitosis, meiosis | |

| Rsk2, MSK1, MSK2 | Immediate-early gene activation | ||

| IKKα | Transcriptional activation | ||

| Thr11 | Dlk/Zip | Mitosis | |

| Ser28 | Aurora-B kinase | Mitosis | |

| MSK1, MSK2 | Immediate-early activation | ||

| Tyr41 | JAK2 | Transcriptional activation | |

| Tyr45 | PKCδ | Apoptosis | |

| H4 | Ser1 | CK2 | DNA repair |

Table 5:Phosphorylation of histones

Ubiquitination

Histone ubiquitination, also known as ubiquitylation, involves attaching ubiquitin to lysine residues. Ubiquitin is an 8.6 kDa protein. While small for a protein, this makes it considerably larger than other histone modifications, with methyl, acetyl and phosphate groups all being under 100 Da. How ubiquitin achieves its effects may be due in part to its large size, sterically hindering the interaction between histones and DNA.35 It can also act as a binding site for chromatin remodelers.

Ubiquitination in the cell more generally is best known as a way of marking a protein for proteasome-dependent degradation. This is particularly true of polyubiquitination, in which lysines within ubiquitin itself are ubiquitinated to form long chains of ubiquitin. In contrast, histone ubiquitination mainly involves monoubiquitination.

All histone core proteins can be ubiquitinated, but the best studied ubiquitination events occur on H2A at lysine 119 and H2B at lysine 120.36 These two events have opposing impacts, with H2AK119ub resulting in transcriptional repression and H2BK120ub associated with transcriptional activation.

Histone ubiquitination has important roles in transcription, chromatin architecture, stem cell plasticity, development, DNA replication, and DNA damage and repair.36–38 Monoubiquitination of H2A, H2A.X and H2B (e.g. H2AK13/15ub) are found at DNA double strand breaks, while polyubiquitination of H2AK63 is an important recognition site for DNA repair proteins.39 These occur in response to extensive histone phosphorylation.

Many of the functions of ubiquitination are achieved via crosstalk with other PTMs. For example, ubiquitination of H2A can recruit methyltransferases such as polycomb repressive complex 1 and 2 (PRC1 and 2), ultimately resulting in methylation of H3K9 and H3K27 for transcriptional repression.37 A similar mechanism exists for H2B ubiquitination, which results in H3K4 and H3K79 methylation, markers of transcriptional activity.37

| Histone | Site | Histone-modifying Enzyme(s) | Proposed Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2A | Lys13 | Rnf168 | DNA damage response |

| Lys15 | Rnf168 | DNA damage response | |

| Lys63 | Rnf18 | DNA damage response | |

| Lys119 | Ring2 | Spermatogenesis | |

| H2B | Lys120 | RNF20/40 | Cell cycle progression, meiosis, DNA damage response |

Table 6:Ubiquitination of histones

ADP-Ribosylation

ADP-ribosylation refers to the transfer of an ADP-ribose group from the co-factor nicotine-amide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) to amino acid residues in histones. While ADP-ribosylation can occur on lysine, arginine, glutamate, aspartate, cysteine, phospho-serine and asparagine residues, lysine and glutamate are the main acceptors in histone proteins.24,40 Proteins can be mono- or poly-ADP-ribosylated, with mono-ADP-ribosylation acting as an acceptor for further ADP-ribosylation.

All core histones can be ADP-ribosylated, and histone H1 in particular is a strong acceptor of poly-ADP ribosylation. Given the role of H1 in chromatin architecture, this suggested that ADP ribosylation may be involved in chromatin structure. Indeed, ADP-ribosylation can directly alter histone-DNA interactions to increase DNA accessibility for transcription factors to increase transcriptional activity, and for repair factors at sites of DNA damage.41,42 ADP ribosylation is also involved in DNA replication and the cell cycle, with poly-ADP-ribosylation being highest during cell proliferation.43

| Histone | Site | Histone-modifying Enzyme(s) | Proposed Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Glu2 | PARP-1 | Neurotrophic |

| Glu14 | PARP-1 | Neurotrophic | |

| Lys213 | PARP-1 | Neurotrophic |

Table 7:ADP-ribosylation of histones

SUMOylation

Histone lysines can be modified with the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) in a similar way to histone ubiquitination. SUMOylation has been observed on residues of all of the core histones in humans, as well as H1 and the variant H2A.X.44 SUMOylation tends to be associated with transcriptional repression, for example by recruiting histone deacetylases (HDACs), which reduce histone acetylation and result in condensed chromatin.44

Other Modifications

Beyond the well-established histone modifications described above, there are many additional modifications to regulate DNA accessibility, replication, repair and transcription. These include:

Many histone modifications are dynamically added or removed from histones in response to external factors or cellular state, such as growth factors, hormones, and cellular stress. This is achieved by enzymes referred to as histone writers and erasers. Writers and erasers therefore allow the environment to modulate chromatin architecture and DNA expression, via intracellular signaling cascades. The enzymes responsible for histone modification are specific to each type of modification, and sometimes specific to precise amino acid residues.

Because of their high specificity and their impact on chromatin structure and gene expression, imbalances between histone writers and erasers can result in in genomic instability and various diseases relating to epigenetic abnormalities, including cancer. Writers and erasers therefore make attractive targets for small molecule inhibitor therapeutics.18,48,49

Table 8 lists writers and erasers of the most common modifications, which will be discussed further below.

| Modification | Writers | Erasers |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylation | Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) | Histone deacetylases (HDACs) |

| Methylation | Histone methyltransferases (HMTs/KMTs) and protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) | Lysine demethylases (KDMs) |

| Phosphorylation | Histone kinases | Histone phosphatases |

| Ubiquitination | Ubiquitin E1 activation, E2 conjugation, E3 ligation enzymes | Deubiquitinases |

| ADP-ribosylation | ADP-ribosyltransferases | ADP-ribosyl glycohydrolases |

| SUMOylation | SUMO E1 activation, E2 conjugation, E3 ligation enzymes | DeSUMOylases |

Table 8:Writers and erasers of histone modifications

HATs and HDACs

Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) are enzymes that add acetyl groups to specific lysine residues on histones. By neutralizing the positive charge of these residues, acetylation promotes gene activation.

Two major classes of HATs exist: type-A and type-B. Type-A HATs tend to be categorized into GNAT, MYST and CBP/p300 families, and are often found in large, multi-protein transcriptional activator complexes. Despite limited sequence homology among type-A HAT families, a structural similarity in the core enzymatic region suggests a common requirement for Acetyl-CoA as a cofactor.50

In contrast, type-B HATs are highly conserved. They predominantly operate in the cytoplasm, acetylating free histones but not those already incorporated into chromatin in the nucleus. Acetylation of such newly synthesized histone H4 at K5 and K12 is important for their deposition into nucleosomes, after which the marks are removed.19

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) play a contrasting role by removing acetyl groups from lysine residues on histones. This deacetylation process effectively restores the positive charge of lysine residues, leading to chromatin condensation and gene repression. 18 mammalian HDACs have been identified and grouped into four classes. Classes I, II and IV are similar in sequence to yeast deacetylases and are zinc-dependent. Class III HDACs are sirtuin proteins and require nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) as a cofactor.

In addition to cofactor requirements, some HDACs need to be in multi-protein corepressor complexes to achieve their full catalytic function.51 This is particularly true of HDACs 1, 2 and 3 in class I, which can join several different complexes depending on cell type, available partner proteins, and environmental context.51

Methyltransferases and Demethylases

Histone methyltransferases (HMTs) add methyl groups histone proteins to regulate gene transcription. Lysine methyltransferase (KMT) activity results in the mono-, di-, or tri-methylation of lysines, while arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) can monomethylate or dimethylate arginine residues. Dimethylation can be either asymmetrical, mediated by Type I PRMTs, or symmetrical, mediated by Type II PRMTs.

HMTs are highly substrate specific: many only methylate a specific histone residue (e.g. H3K4), though there can be several different enzymes capable of methylating a single residue.52 Such enzymatic redundancy can make methylation events highly context-specific.

Histone demethylases (KDMs) remove methyl groups. LSD1 was the first KDM to be identified, and the discovery of the Jumonji C (JmjC) domain being a signature of demethylases further broadened the number of known KDMs.53 Similar to HMTs, KDMs exhibit high specificity for particular methyllysine or methylarginine residues.

Kinases and Phosphatases

Histone kinases add phosphate groups to serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues. Some key kinases, such as aurora B kinase, act as master regulators, coordinating the activity of several histone kinases.54

Histone phosphorylation often defines large regions of chromatin, such as different regions of the centromere during mitosis, which can help to provide clear signals to chromatin remodeling factors. These large regions emerge as a result of positive feedback loops involving phosphorylation of both histones and kinases.54 For instance, the kinase Haspin phosphorylates H3T3, which recruits Aurora B kinase. Aurora B in turn phosphorylates Haspin to drive more modification of histones nearby.

Kinases such as MSK1/2 that are capable of phosphorylating both histones and transcription factors can also result in rapid upregulation of target genes by activating transcription factors and opening up chromatin, making them invaluable in fast responses to external signals.55

Histone phosphatases tend to be common cellular phosphatases that are capable of dephosphorylating a wide array of different phosphorylated proteins, including histones. PP1, PP2A and PP4 have all been identified has being able to dephosphorylate histones.54 To achieve specificity, targeting factors such as Repo-Man are required for recruitment to chromatin.

Histone readers are proteins that recognize different histone modifications and respond based on the modifications present. Such responses can include chromatin remodeling and recruitment of transcription factors. While histone writers and erasers are responsible for adding and removing different functional modifications, it is likely that histone reader proteins are the core determinants of the ultimate effects of the histone code present in a given location.

Histone modifications are read by specialized domains or modules. Specificity of these modules is determined by residues in close proximity to the module’s binding pocket. Even minor sequence changes can modify recognition, including between highly similar epigenetic marks such as mono-, di- or tri-methylation.56

Table 9 describes various histone recognition domains that are found in reader proteins, which histone modifications they recognize, and their likely roles in cellular activity.

| Histone-binding or Effector Domain | Proteins Containing Domain | Known Histone Marks | Suggested Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14-3-3 | 14-3-3 Family | H3S10ph H3S28ph | Recruit transcriptional machinery and enhance acetylation of neighboring lysine residues, promoting an open chromatin state and increasing gene activation at binding sites.57,58 |

| Bromodomain | BRD2, BRD4, BAZ1B, BRG1 | H3K9ac H3K14ac H4K5ac H4K8ac H4K12ac H4K16ac | Recognize acetylated lysine residues. Recruit transcriptional machinery and co-activators to acetylated regions to promote gene expression and facilitate chromatin remodeling.59 |

| BRCT | 53BP1, BRCA1, MDC1, NBS1 | H2A.XS139ph | BRCT domains bind phosphorylated serine and threonine residues. Recognize phosphorylated histones at sites of DNA damage to recruit DNA repair machinery. Can also recruit transcriptional regulators to promote transcription.60,61 |

| Chromodomain | CHD1, CDY, HP1, MPP8, MRG15 | H3K4me2/3 H3K9me2/3 H3K27me2/3 | Recognize methylated lysine residues and can be associated with either gene activation or repression via changes to chromatin state.62 |

| MBT | L3MBTL1, L3MBTL2, MBTD1 | H3K4me1 H4K20me1/2 H1K26me1 | MBT domains recognize and bind to methylated lysines. Involved in chromatin compaction and gene repression.63–65 |

| PHD Fingers | BPTF, ING, RAG2, BHC80, DNMT3L, PYGO1, JMJD2A, UHRF, PHF20 | H3K4me3 H3K9me3 H3K36me3 H3K14ac | Recruit transcription factors and chromatin remodeling proteins involved in gene activation or repression, depending on the specific mark. Play roles in chromatin remodeling and gene regulation.66 |

| Tudor Domains | TDRD3, TDRD7, 53BP1, SETDB1 | H3K4me3 H3K9me3 H3R17me2 H4K20me2 | Tudor domains bind to methylated lysines and arginines, particularly trimethylated lysines, resulting in either activation or repression of gene expression depending on the specific protein. Involved in various processes, including DNA damage response and gene regulation.67,68 |

| WD40 repeats | WDR5, EED, LRWD1, WDR77, RbBP4/7 | H3K4me2 H3R2me2 H3K9me3 H3K27me3 | Typically recognize methylated lysines, and they can recruit transcription factors and chromatin remodeling proteins involved in gene activation or repression, depending on the specific mark.69-71 |

Table 9: Histone reader domains and their cellular functions.

Multivalent Histone Modifications

Combinations of histone modifications can be recognized by histone readers that contain multiple histone-binding modules within them, either as individual effector proteins or as complexes.56 Such multivalent interactions greatly expand the nuance and complexity of the histone code, whereby histone modifications are read together rather than in isolation. Modifications to be read simultaneously can be on the same histone tail, but they can also be further apart on the same nucleosome, on neighboring nucleosomes, or on nucleosomes that are not close on a contiguous stretch of DNA but are spatially located in common chromatin territory.56 How combinatorial modifications are read can depend on nucleosomal context.72

This mechanism reinforces common markers of chromatin states, enabling histone readers to form stable interactions with modified regions of chromatin despite relatively weak binding affinity for individual modifications.73

One well known multivalent modification is H3K4me3 and H3K27me3, which is present together almost exclusively in pluripotent stem cells and is thought to help maintain the pluripotency of the cell population.74 Others have been recognized as being involved in gene silencing, X-chromosome inactivation, and responses to external signals.56

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

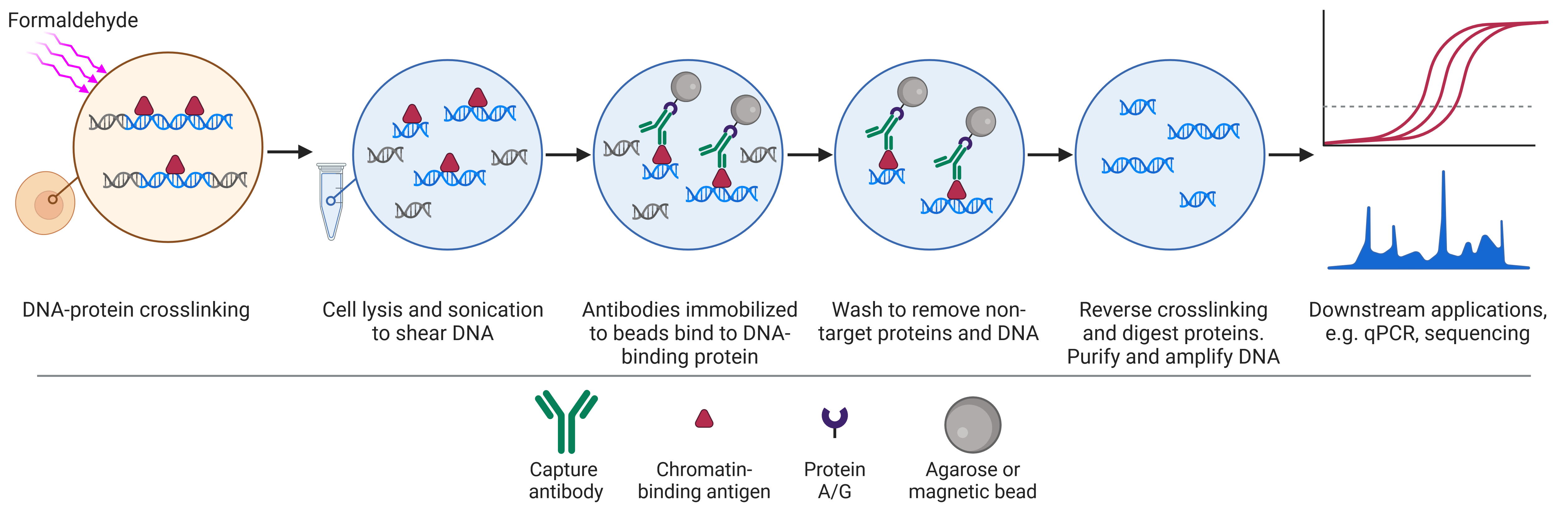

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) is a biochemical technique that uses antibodies to bind to and isolate proteins of interest alongside any DNA it is bound to (Figure 4). The DNA can then be purified, sequenced, and mapped to the genome to determine where the protein of interest was bound in the genome and its abundance at different sites.

Figure 4: Schematic of chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) workflow.

The experimental aims and outcomes vary depending on the identity of the protein of interest. Antibodies against histone proteins or even specific histone modifications can be used in ChIP for a number of questions, including:

Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) provides a comprehensive view of the histone modification landscape in an unbiased manner. For MS, histones are enzymatically digested into peptides, which are then ionized and separated within the spectrometer based on their mass-to-charge ratio. The resultant spectra can then be analyzed to determine the presence and abundance of specific histone modifications.

MS has several advantages over ChIP. It is highly quantitative, providing precise measures of abundance. MS is not limited to a specific region of the genome or to specific types of modifications as antibodies would be, meaning it is unbiased and can provide a complete picture of all modifications that change during an experimental treatment. This makes it ideal for investigating combinatorial changes, such as if both acetylation and methylation are altered. Novel PTMs can also be identified by MS.

Western Blot

Western blots use antibodies to detect proteins on a membrane that have been separated based on their size by gel electrophoresis. They are useful for gaining an understanding of the relative abundance of specific histones (e.g. histone variants) or histone modifications, which can then be compared across different experimental conditions. They are more targeted than MS, capable of investigating only a few modifications at a time with specific antibodies. However, they are still capable of investigating combinatorial modifications by sequential or parallel blotting.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) uses antibodies to detect and visualize histones and their modifications in tissue samples. This allows researchers to observe the spatial distribution of histone modifications in the cell, such as in different types of chromatin or different cellular structures. IHC is particularly useful for studying the localization of modifications during stages of the cell cycle. It can also be used to investigate combinatorial modifications, with complementary antibodies targeting specific modifications and techniques such as Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) or proximity ligation assay (Figure 5).75

Figure 5: Using immunohistochemistry to detect histone modifications in mouse embryonic stem cells.A-D, Individual antibodies against specific modifications can be used to reveal the localization of histone modifications within the nucleus and suggest colocalization (A-C) or not (D). E-H, Proximity ligation assay will only generate a fluorescent signal when targeted proteins or modifications are within ~30 nm of each other (E-G). No signal is seen if they are not in close proximity (H). Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI.

Edited and reproduced under Creative Commons 4.0 CC-BY from Hattori, N., Niwa, T., Kimura, K., Helin, K. & Ushijima, T. Visualization of multivalent histone modification in a single cell reveals highly concerted epigenetic changes on differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 7231–7239 (2013).

Diagrams created with BioRender.com.