Ryan Hamnett, PhD | 30th September 2024

The clonality and purity of an antibody preparation are key determinants of what the antibody can be used for, though both polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies are used extensively in biomedical research. While polyclonal antibodies more accurately reflect the endogenous response to an immune threat, the development of monoclonal antibodies in the 1970s has made it possible to produce near-infinite stocks of reliable antibodies, allowing them to be used as effective therapeutics of human disease. Antibody technologies continue to be developed, with recombinant antibodies opening up more options for intentionally engineering antibodies with precise binding sites and structures.

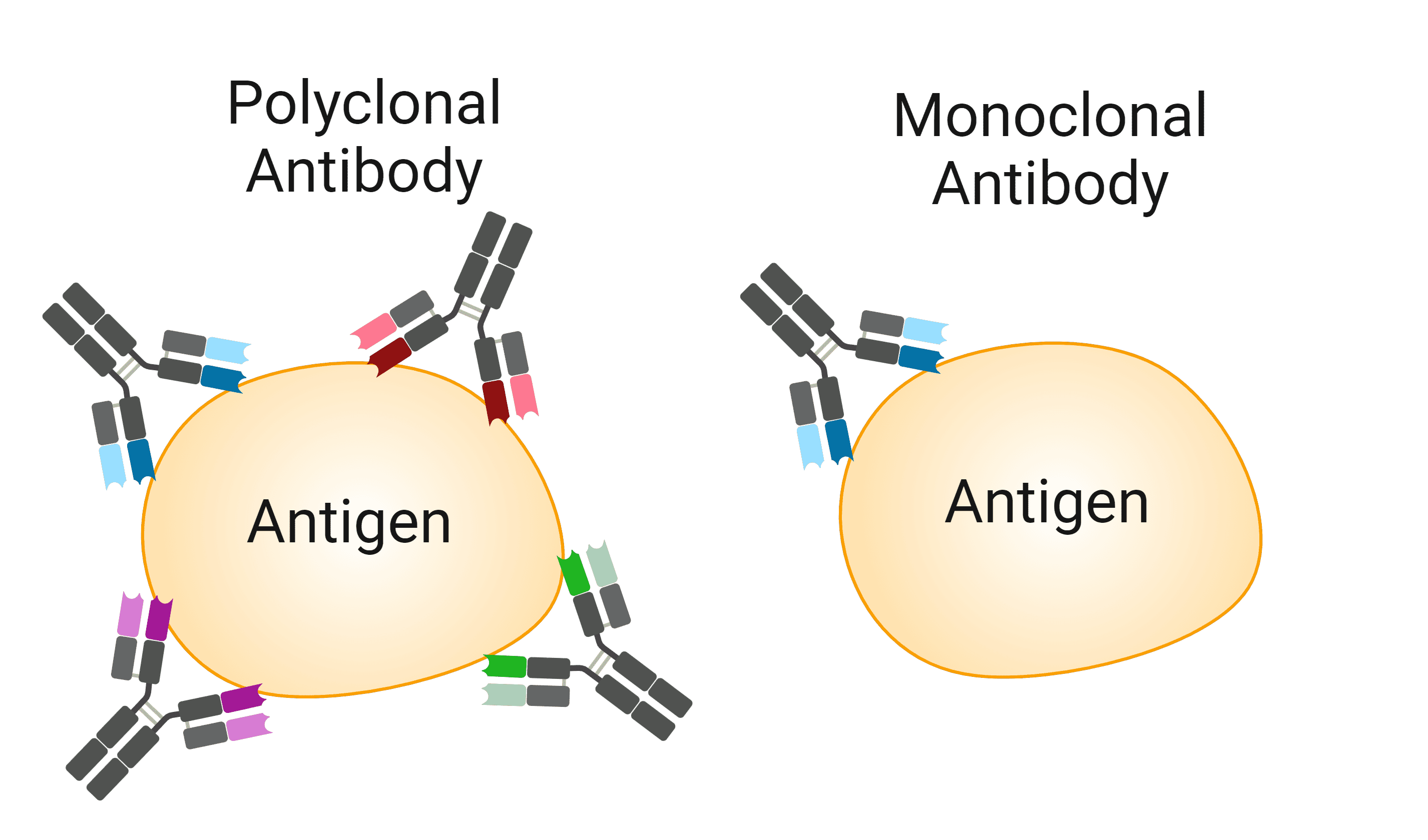

The clonality of an antibody preparation ultimately refers to whether it was derived from a single plasma B cell or multiple. This will determine how many epitopes it binds to (Figure 1), and, for antibodies used in research, how the antibody was produced.

Figure 1: Polyclonal vs monoclonal antibodies. Polyclonal antibodies are heterogeneous populations of antibodies that bind to multiple epitopes on an antigen. Monoclonal antibodies will only recognize a single epitope on an antigen. Created using BioRender.

When an antigen is detected by the immune system, many different B-cells are likely to respond to it, proliferate, and generate antibodies against it, potentially recognizing different epitopes on the antigen. Isolating all of the antibodies made against a given antigen will produce a polyclonal antibody. Polyclonal antibodies are therefore heterogenous mixes of antibodies, capable of binding to multiple epitopes on an antigen.

In contrast, monoclonal antibodies consist of identical copies of just one type of antibody, produced by cells of a clonal (i.e. derived from a single parent) B-cell population. This means that monoclonal antibodies will only bind to a single epitope on the antigen.

Polyclonal Antibodies

Polyclonal antibodies recognize multiple epitopes on an antigen because they are derived from multiple antibody-producing B-cells. As a result, polyclonal antibodies have both advantages and disadvantages for the end user over monoclonal antibodies, listed in Table 2 below.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| More epitopes being recognized means they are less likely to be affected by conformational changes to proteins, such as denaturation | May be more likely to bind to off-target proteins due to more epitopes being recognized, which could lead to higher background signal |

| May give stronger signal | Finite supply of a given antibody lot |

| Less expensive and faster to produce | Lot-to lot variability due to method of production |

| Produced in a greater variety of organisms, including goat, guinea pig and chicken, giving more flexibility for multiplexing |

Table 2:Key features of polyclonal antibodies

The features in Table 2 can make polyclonal antibodies the preferred choice for some applications. For example, polyclonals are often preferred for immunoprecipitation because they tend to have a higher chance of capturing the target protein. Their availability from multiple host animals also makes them suitable for multiplexed IHC and ICC.

Monoclonal Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies correspond to one epitope for a given antigen because they are derived from a clonal population of B-cells. Advantages and disadvantages of monoclonal antibodies are outlined in Table 3.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| One epitope being recognized gives them greater specificity | Longer development and more expensive to produce |

| Binding site is known, which is often not the case with polyclonals | Less robust to conformational changes of the antigen during biochemical processing |

| Less likely to exhibit off-target binding and therefore give lower background signal | Usually only available from mice or rabbits, which can limit multiplexing |

| Constant supply with little lot-to-lot variability | Using mouse antibodies with mouse tissue (mouse-on-mouse) can produce significant non-specific interactions, which is an issue given how prevalent mice are as a model organism |

Table 3:Key features of monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies are often the preferred choice in laboratories requiring large amounts of identical antibody or performing the same procedure repeatedly over time due to the consistency in monoclonal production. They are also ideal for designing matched pairs of antibodies in sandwich ELISAs, because known binding sites makes it easier to find two complementary antibodies.

Clone number

Monoclonal antibodies are always given a clone number, which represents the specific cell line that the antibodies were produced from. All antibodies with the same clone number are derived from the same clonal population. This means that all antibodies with the same clone number will have the same structure, affinity and specificity as each other. Because multiple monoclonal antibodies may exist for a single target, clone numbers are used to identify antibodies to ensure that exactly the same antibody is being used as in previous experiments.

Mouse vs Rabbit Monoclonal Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies tend to be made in either mouse or rabbit host cells. The availability of only two hosts can limit multiplexing in application such as immunohistochemistry, forcing researchers to consider a sequential labelling and stripping strategy, or directly conjugated primary antibodies.

For many researchers, the choice between mouse and rabbit will mostly come down to cost and availability of antibodies against their target of interest. However, there are some differences to be aware of.

A significant implication of monoclonal antibodies being produced in mouse is that using mouse antibodies with mouse tissue (mouse-on-mouse) can produce significant non-specific interactions. This is an important issue given how prevalent mice are as a model organism in some areas of research and as disease models.

Rabbit can also be preferred because rabbits are able to mount an immune response against a wider range of antigens, including small peptides or other molecules. This means that an antibody against a small molecule is more likely to be available from rabbit. Rabbit antibodies can also exhibit higher affinities for their targets, producing a stronger signal for end users.

Rabbit monoclonals are more expensive to produce, however. Mouse monoclonal technology has been used for much longer than rabbit, meaning that there is more likely to be a mouse monoclonal antibody against a given target than rabbit.

The ability to engineer class switching is therefore more established in mice as well. Class switching refers to when the cells producing the antibodies switch the constant region of the antibody, and therefore its isotype, while retaining the variable region and its specificity against the epitope. Using multiple isotypes can be one solution to the issue with multiplexing mentioned earlier, and can be easier in mice because they have multiple IgG subclasses (IgG1, IgG2a/2c, IgG2b, and IgG3) whereas rabbits only have one.

Finally, the technology for producing recombinant antibodies is also more established in mice.

See our comprehensive guide on Rabbit Monoclonal Antibodies for more information on their advantages and uses.

Recombinant Antibodies

Recombinant antibodies are monoclonal antibodies that are generated using recombinant DNA technology, meaning the exact DNA sequence needed to produce an antibody with a given target specificity is known and can be expressed in cell lines. This is in contrast to the hybridoma technology usually used to produced monoclonal antibodies (see Antibody Production).

In general, recombinant antibodies retain all of the benefits of monoclonal antibodies, but provide a greater deal of control over their production. For example, while traditional monoclonal antibodies exhibit little lot-to-lot variability when compared to polyclonal antibodies, some genetic drift can occur leading to slight variation due to acquired mutations. Knowing the DNA sequence avoids this drift. Recombinant antibodies can also be easily modified, such as to different isotypes or formats.

More information can be found on our Recombinant Antibodies page.

Multiclonal Antibodies

Multiclonal antibodies address the issue of monoclonal antibodies targeting only one epitope. While this is often seen as an advantage, targeting a single epitope does make monoclonals less robust to conformational changes in the antigen, and can limit the strength of signal produced on binding.

Monoclonal antibodies are produced as normal, and then combined together into a tube to produce multiclonal antibodies. This gives the beneficial property of polyclonals of being able to bind to multiple epitopes to produce a stronger signal, while retaining the known binding sites and high specificity of monoclonal antibodies.

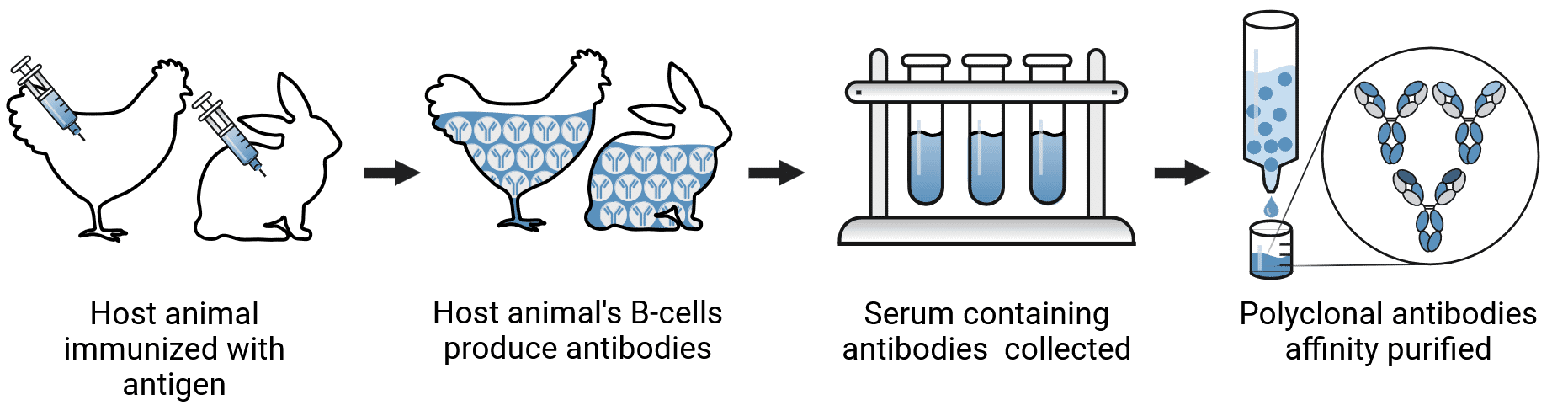

Polyclonal Antibody Production

Polyclonal antibody production (Figure 2) tends to be easier than for monoclonal antibodies. The general steps involved in their production are as follows:

Figure 2: Polyclonal antibody production.

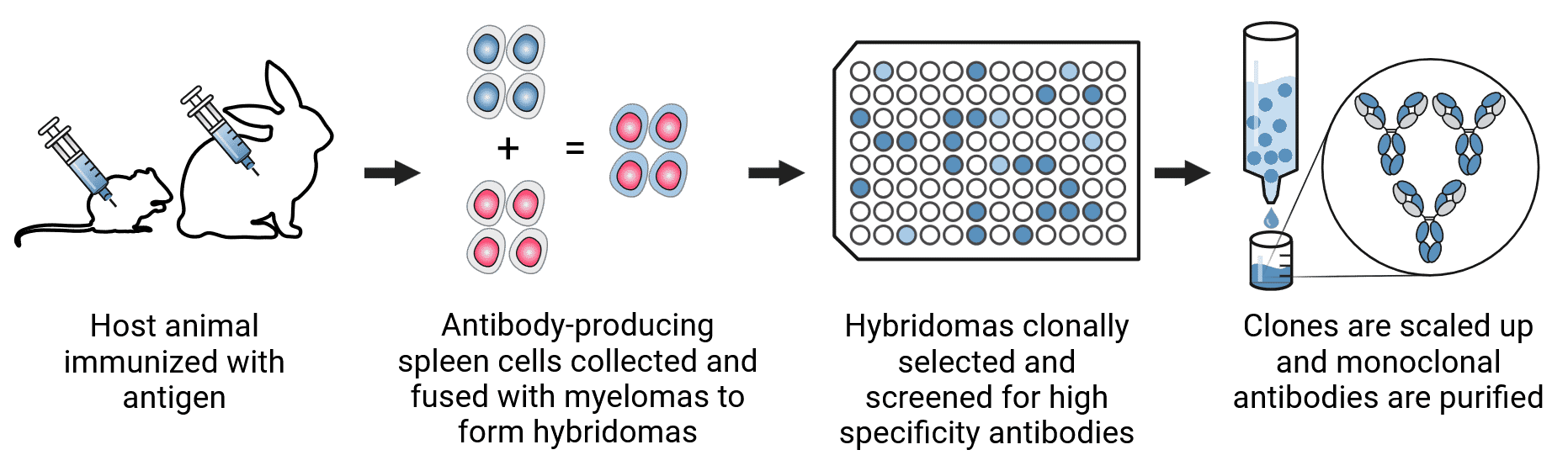

How Monoclonal Antibodies are Made

Monoclonal antibody production (Figure 3) usually begins with similar first steps as polyclonal production. Antigens are purified and immunized into a selected host (usually mouse or rabbit). The titer of antibodies in the serum is determined by collecting a small amount of blood from the immunized animal and determining antibody concentration by ELISA or other method. The production procedure then follows these steps:

Figure 3: Monoclonal antibody production.

Recombinant Antibody Production

Recombinant antibodies are not made by hybridomas, and do not require a live animal at any point. Instead, they are made using display technology, typically phage display for antibody fragments or display systems in higher organisms (yeast, insect, mammalian cells) for more complex antibodies.

Briefly, phage display involves creating a library of millions of bacteriophages where each phage expresses and presents a single antibody on its surface. These phages are then screened against an antigen that has been immobilized on a plate. Phages expressing antibodies that are specific for that antigen will remain bound, while others are washed away. The selected phages are eluted, amplified in E. coli, and can be subjected to screening again to find the highest affinity antibodies. Once the target-specific phages have been validated, the DNA sequence of highly specific antibodies, derived from selected phages, can be used for recombinant antibody production in an expression system of choice.

More details of recombinant antibody production can be found on our Recombinant Antibodies page.

Antibodies can be obtained at several different levels of purity. How pure an antibody needs to be depends on the intended application.

Antiserum

Antiserum is blood serum containing polyclonal antibodies of interest, as well as other serum proteins and immunoglobulins. This can be further enriched by isolating just the immunoglobulin fraction of the serum. Antiserum is more likely to show off-target activity due to contaminants.

Ascites

This is a historical method of producing monoclonal antibodies that has mostly been superseded by recombinant technology. Once hybridoma cells had been produced, they were injected into and grown within the peritoneal cavity of a mouse or rat. After proliferation, they produce a fluid called ascites, which contains a high antibody concentration and can be harvested. The ascites method can also produce cell lines that show enhanced antibody production at a later time.

Tissue Culture Supernatant

Supernatant from hybridoma cultures can be directly used in antibody applications, assuming the concentration of the antibody is high enough.

Purified

Most researchers use purified antibodies, particularly if purchasing a commercial antibody. Nonetheless, there are different degrees of purification.

Protein A and Protein G bind to the Fc region of antibodies with high affinity, and can therefore be used to isolate all immunoglobulins from antiserum. They will not show any selectivity for a target antibody, however, so there may still be off-target activity.

Affinity purification purifies proteins by making use of strong and specific interactions between the protein of interest and a resin coupled to a ligand. In the case of antibodies, the target antigen can be coupled to the resin on a column. The crude sample containing the antibody is then washed over the resin; antibodies will bind to the antigen and stay on the resin, while everything else will be washed through. The antigen-antibody interaction can then be disrupted to elute the pure antibody of interest.

Pre-adsorption is a final step to distinguish closely related antibodies, and is usually applied to secondary antibodies (e.g. antibodies that are specific for another type of antibody). A sample of secondary antibodies is washed across a column containing immobilized serum proteins from non-target species that are likely to be cross-reactive. Non-specific antibodies will bind to the proteins, leaving only the highly specific antibodies to flow through.