Ryan Hamnett, PhD | 30th September 2024

Antibodies are powerful tools for research and are used in a wide array of laboratory techniques. Each of these applications can answer distinct questions about the proteins within a biological sample, including how abundant a protein is, how it has been modified, where it can be found in a cell, and which other biomolecules interact with it.

In addition to the outlines below, Antibodies.com has written comprehensive guides on each of the following techniques, which can be found on our Applications page.

Prior to employing an antibody to answer a biological question, it is important to verify that the antibody binds to its intended target. There are various different types of antibody validation described below that can help to ensure reliable and reproducible results.

ELISA

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) uses antibodies to detect and quantify the amount of target antigen in a liquid sample such as serum (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Sandwich ELISA overview. A capture antibody immobilizes an antigen from a sample. The enzyme-conjugated detection antibody binds to a distinct epitope on the antigen, and catalyzes the production of a colored substrate. The amount of color produced is proportional to the amount of antigen. Created using BioRender.

ELISAs are usually performed using a multi-well plate, with each well containing immobilized antigen or antibody, depending on the format. A sample is added to each well, allowing specific interactions to form between antibodies and analyte, before unbound or loosely bound sample is washed away. A conjugated detection antibody provides the means to measure how much of the target was in each sample, by producing a colored, fluorescent or luminescent signal proportional to the amount of analyte.

The main types of ELISA are direct, indirect, sandwich and competitive. Each format offers different advantages, with sandwich usually being the most specific due to its use of two complementary antibodies.

ELISAs are useful not only for their quantifiability, but also because they are usually performed in a 96- or 384-well plate, making them amenable to running many samples at once. They are now commonplace in both research and diagnostic applications.

Flow Cytometry

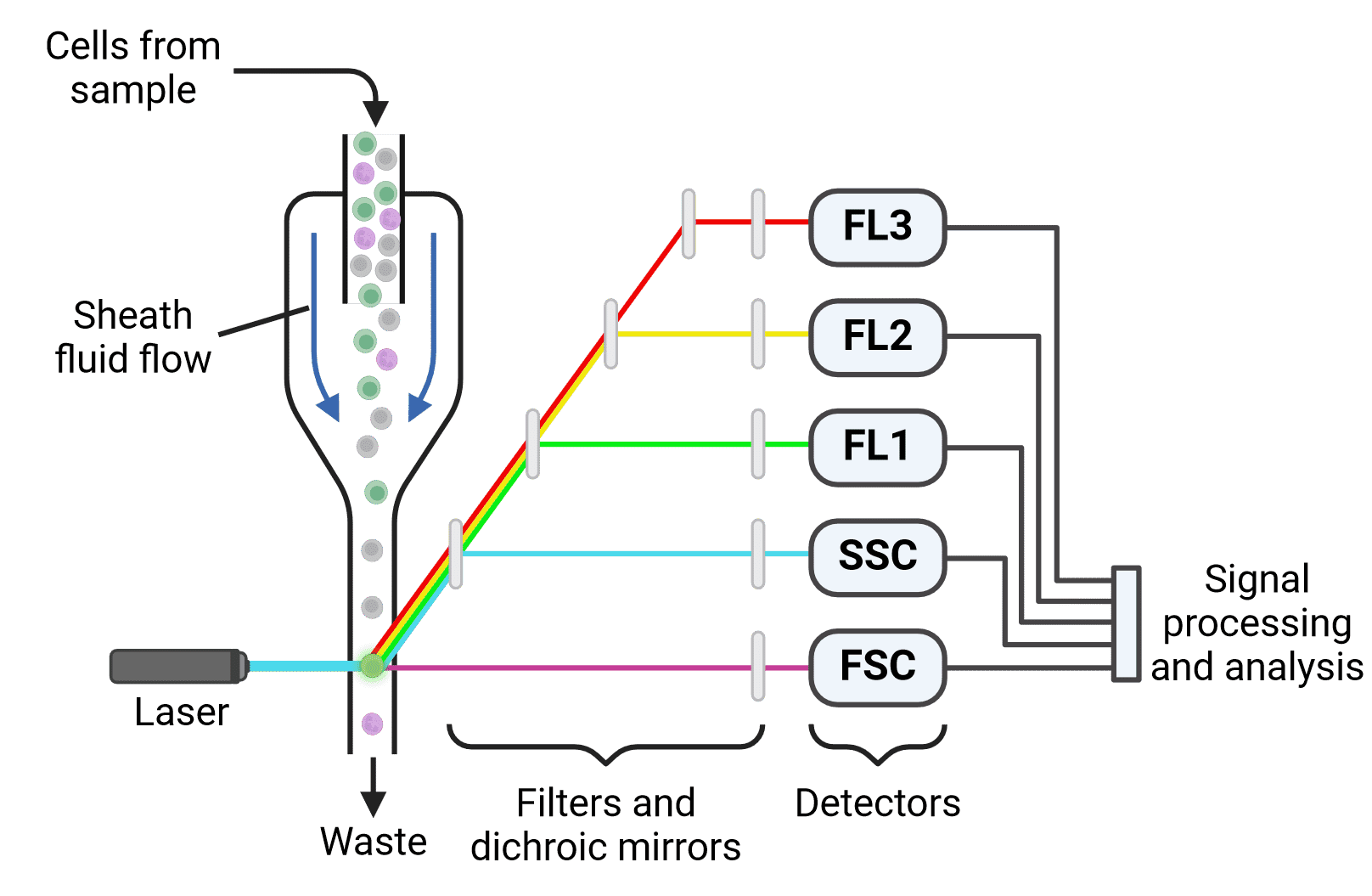

Flow cytometry uses light to characterize and measure heterogeneous suspensions of particles such as cells (Figure 2). While flow cytometry initially characterized cells based on their physical properties (e.g. size and granularity), it has evolved to make extensive use of antibodies and fluorophores. This enables the measurement of dozens of cellular characteristics and the identification of many cell subpopulations in modern flow cytometry experiments.

Figure 2: Flow cytometer set up. Cells pass through a laser beam one at a time. Fluorescence measurements (FL1-3), as well as forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC), are collected for each cell and analyzed to identify different cell populations. Created using BioRender.

Flow cytometry involves creating or collecting a suspension of cells (immune cells in blood, for example), and labeling them with fluorescently conjugated antibodies. Cell surface proteins are often labeled, but intracellular proteins can be studied with flow cytometry as well. The cells are then run through a flow cytometer, which passes thousands of cells per second past one or several lasers to analyze the fluorescent signal of each cell. Based on these fluorescence values (and careful controls), the numbers and percentages of specific cellular subtypes within a mixed population can be determined.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) is a special application of flow cytometry that sorts cells based on their characteristics by giving selected cells an electrostatic charge and then sorting them into different containers with a magnetic field. This is useful if the cells are needed for downstream applications such as RNA sequencing or cell culture.

Flow cytometry is high throughput and provides measurements of multiple parameters per cell, making it highly suitable for many research applications and diagnostic tests.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC), Immunocytochemistry (ICC), and Immunofluorescence (IF)

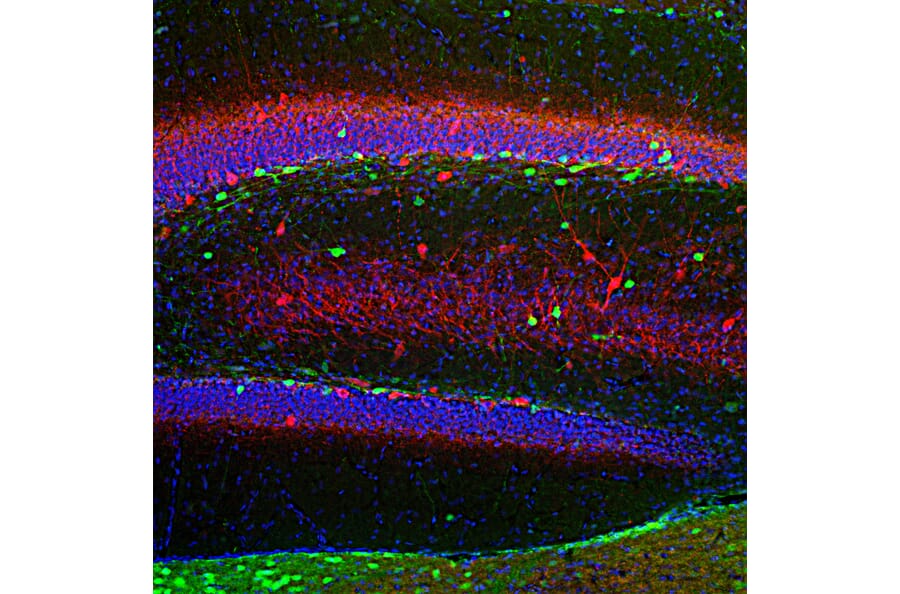

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunocytochemistry (ICC) describe related techniques for using antibodies to detect and visualize proteins in a biological sample (Figure 3). IHC refers to detection of proteins in tissue (e.g. sections or wholemount), whereas ICC looks at samples of cells.

Figure 3: Fluorescent immunohistochemistry. Rat hippocampus section was stained with Anti-Calretinin Antibody (A85366), at 1:2,000, in green, and and co-stained with Anti-Parvalbumin Antibody (A85316), at 1:1,000, in red. Nuclear DNA is stained by DAPI (blue).

Visualization can be either colorimetric/chromogenic or fluorescent, in which case it can also be referred to as immunofluorescence (IF) (Figure 4). IF involves directly visualizing fluorophores that have been conjugated to antibodies, while colorimetric detection involves conjugating antibodies to enzymes that catalyze a chemical reaction to produce a colored product. Colorimetric detection is still frequently used in IHC, but IF has almost completely superseded colorimetric methods in ICC. Hence, ICC and IF are sometimes used interchangeably. Greater multiplexing, or simultaneous detection of multiple colors, is generally easier in IF than colorimetric. This is because the nature of fluorescence makes it possible to visualize just one color at a time with excitation lights and emission filters of appropriate wavelengths.

All methods begin with fixing the biological sample to preserve proteins in their native state. Primary antibodies are then incubated with the sample to allow binding to the target. A blocking buffer can be used before antibody addition if necessary to reduce non-specific interactions between the antibody and tissue components. The primary antibody may be directly conjugated to a fluorophore or colorimetric enzyme, or a secondary antibody that binds to the primary antibody may be needed (see Direct or Indirect?). Visualization is then performed on a microscope.

IHC is commonly used in pathology laboratories to check for signs or markers of disease. IHC can be used as both a diagnostic and prognostic tool for conditions such as cancer, and bacterial, viral and fungal infections.

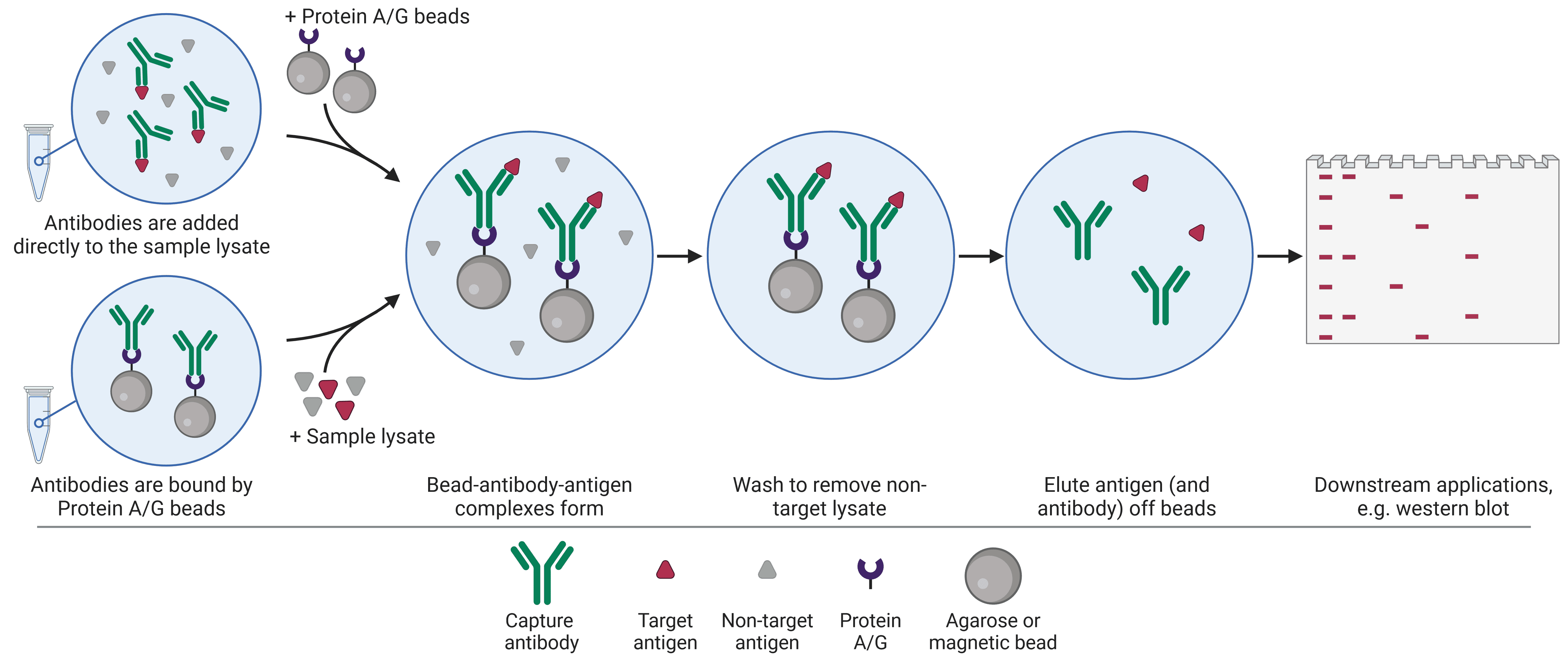

Immunoprecipitation (IP) and Co-IP

Immunoprecipitation (IP) uses antibodies attached to beads to isolate proteins of interest from a complex sample (Figure 5). Once a protein of interest has been captured by the antibody-bead complex, all other cellular components are washed away and the protein can be eluted. Proteins that have been purified by IP can then be further investigated using another technique such as ELISA, western bot or mass spectrometry.

Figure 5: Overview of the immunoprecipitation procedure. Created using BioRender.

Co-IP is an extension of IP that purifies not only the protein that is specifically bound by the antibody, but also other proteins that interact with the protein targeted by the antibody. These can include activators, inhibitors, kinases or other mediators of post-translational modifications (PTMs), ligands, and so on. Co-IP is therefore a powerful technique for investigating protein-protein interactions. Co-IP follows broadly the same procedure as IP, though lysis and wash conditions tend to be milder in order to preserve fragile protein-protein interactions.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

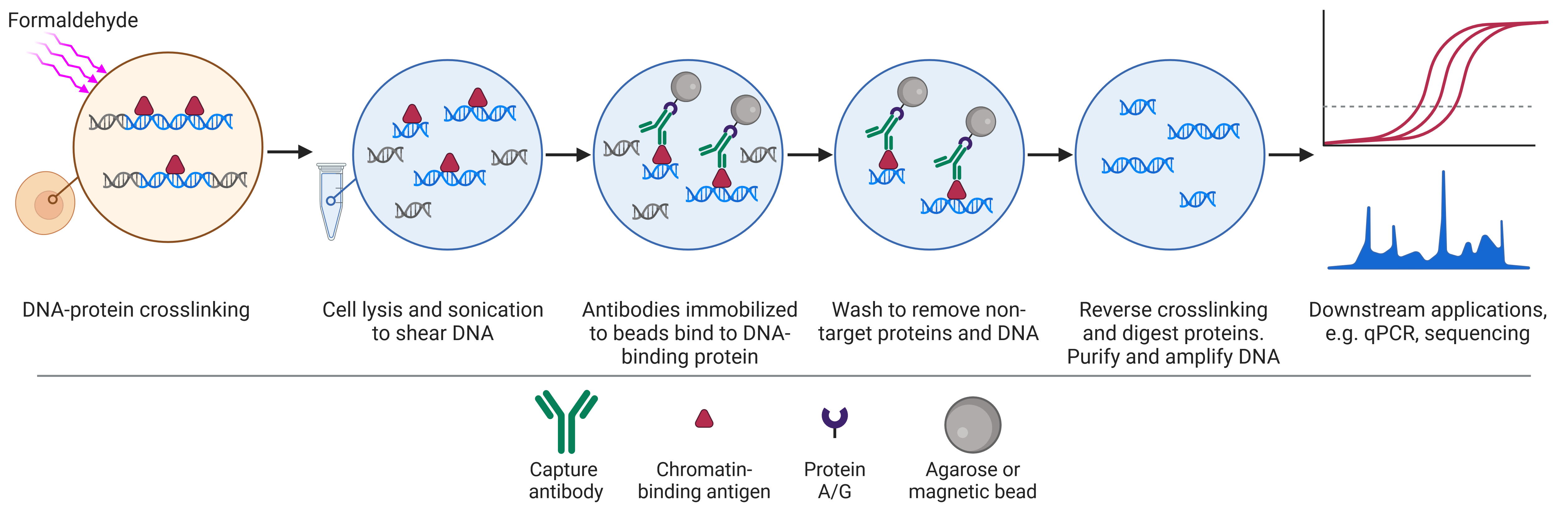

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) is a variant of the IP technique that uses antibodies on beads to purify proteins attached to DNA sequences (Figure 6). The DNA can then be recovered for PCR or sequencing and mapped to the genome. This allows researchers to determine what kinds of sequences the target protein binds to and how binding to specific sequences changes with experimental treatment.

Figure 6: Overview of the chromatin immunoprecipitation procedure. Created using BioRender.

If the target protein is a histone protein, one of the core components of chromatin itself, ChIP can be used to investigate chromatin structure and to identify active or silent regions of the genome based on histone modifications.

The ChIP procedure begins with crosslinking proteins and DNA to maintain protein-DNA interactions. Cells are then lysed and the DNA is sheared to produce small fragments of DNA attached to proteins. Antibodies attached to beads can then capture the protein-DNA complexes. Once captured, crosslinking is reversed and the proteins are removed to leave pure DNA for analysis.

A variant on ChIP, called RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP), looks at protein-RNA interactions instead of protein-DNA interactions.

Western Blot

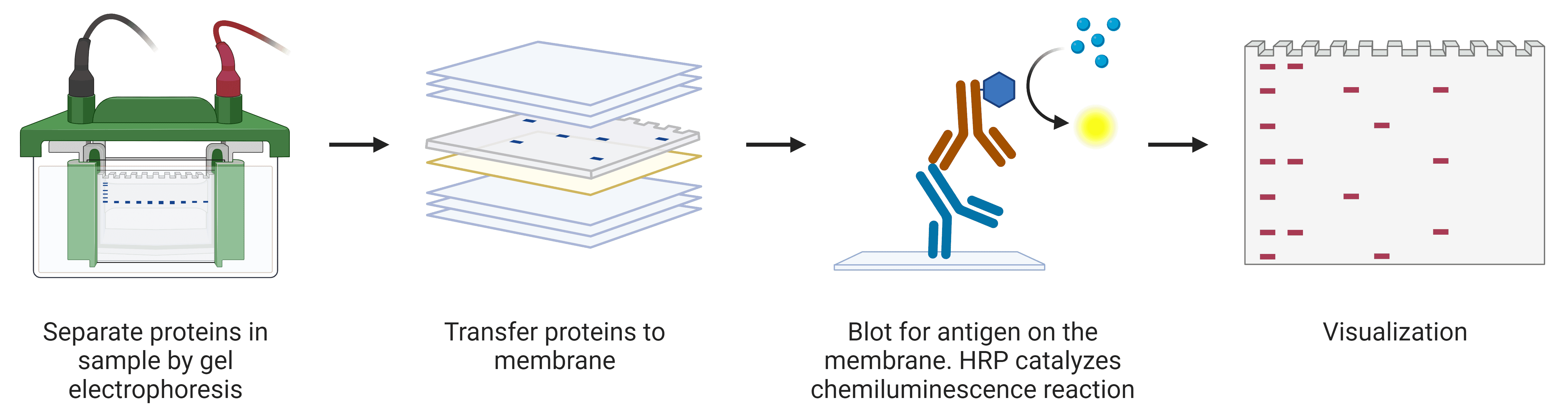

Western blot is a common biochemical technique that uses antibodies to detect specific proteins on a membrane that have been separated by weight by gel electrophoresis (Figure 7). This allows investigations into protein abundance and the molecular weight of proteins or protein complexes, which can shed light on post-translational modifications.

Figure 7: Overview of western blot procedure. Created using BioRender.

Western blots begin with lysing samples to free the cellular contents. The proteins are then denatured using sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and heat so that proteins can be reliably separated by molecular weight. Separation of proteins is achieved by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), where proteins separate according to size on the basis of their speed of migration through the gel. The proteins are then transferred to a membrane, which is incubated with antibodies for detection of the target.

Antibodies are generated by the immune system to be highly specific for a particular foreign substance and to bind with high affinity. However, antibodies can cross-react with off-target proteins if similar epitopes are present, which can confound experimental interpretation when using antibodies in a research setting. This is why it is important to validate the specificity of antibodies, to ensure that they are binding to the target protein with as few non-specific interactions as possible.

Methods used by Antibodies.com to validate our antibodies can be found on our Product Validation page.

Knockout (KO) Validation

Knockout (KO) validation is the gold standard method for determining how specific an antibody is for its target antigen. In this approach, the expression of the protein in a wild-type sample is compared to a sample that has been genetically modified to lack the protein of interest. If the antibody is highly specific, there should be no signal in the KO condition (Figure 8). Any signal in the KO condition indicates that the antibody is binding non-specifically.

Figure 8: Example of knockout validation performed by western blot. The lack of any signal in the EGFR KO lane indicates that the EGFR antibody is specific.

Genetic KO cells or organisms can be made by several different techniques, such as homologous recombination, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9. CRISPR-Cas9 has become the method of choice due to its greater flexibility, efficiency, and specificity compared to other gene editing technologies.

KO validation can be performed using multiple techniques, but is most commonly done by ICC or western blot.

More information on KO validation can be found on our Knockout Validation page.

Protein Array Validation

Genome-wide protein arrays assess the specificity and selectivity of antibodies against 19,000+ full-length proteins. These confirm whether an antibody binds to only one target, as well as the number, identity and affinity for off-target proteins.

Protein arrays work by spotting proteins onto an array, and then incubating the antibody being tested with the array. After allowing it to bind to its target and any cross-reactants, a fluorescent secondary antibody allows visualization of all binding spots, which can be quantified, with more binding producing a stronger signal.

Biophysical Validation

New forms of biophysical validation are providing extra levels of assurance that an antibody preparation is as pure and specific as possible. For example, traditional assessments of purity and monodispersity relied on SDS-PAGE analysis. Size-exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography (SEC-HPLC), a gold-standard biophysical test that uses porous beads to separate molecules by size, now enables easy visualization of any aggregates present in a sample (Figure 9). All biosimilar antibodies sold by Antibodies.com are assessed by SEC-HPLC, as well as extensive functional testing.

Figure 9: Purity assessment by SDS-PAGE (left) and SEC-HPLC (right) of Bemarituzumab Biosimilar - Anti-FGFR2 Antibody. In SDS-PAGE, one band is observed in non-reducing (NR) conditions, while reducing (R) conditions shows two bands that represent the heavy and light chains of the antibody. In SEC-HPLC, a quantification of the percentage area under a given peak is precisely determined.

Other Methods of Validation

In addition to KO validation, the International Working Group for Antibody Validation also identified four other pillars of antibody validation following knockout validation:

Controls

Controls allow interpretation of the results of antibody validation tests.

A positive control is a cell or tissue sample that strongly expresses the target of interest. An antibody being tested should give a strong signal when binding to this control sample.

A negative control is a cell or tissue sample that does not express the target of interest. A specific antibody should not produce any signal in a negative control.

Controls can be cell or tissue samples that naturally express the protein of interest in high or low abundance. Databases such as UniProt or Protein Atlas, as well as the scientific literature, are useful sources of information on which cells do and do not express proteins and could be suitable as control samples. For tissues in particular, controls may be part of the same sample as the experimental sample, such as an area of the brain known to strongly express a target protein in a brain section. In many ways this is ideal, because experimental processing and treatments will have been identical between the two areas.

If it is not possible to find a cell line or tissue that expresses the target protein at the desired level, controls can be engineered. For a positive control, this may involve overexpressing the protein via plasmid transfection or viral transduction, or by treating the cell with something known to induce strong expression. For negative controls, a KO sample is ideal, such as one created by CRISPR. If a protein is essential to basic cellular functioning, KOs may not be viable, in which case a knockdown (e.g. by siRNA/shRNA) might be preferable.

Though the general controls described above are relevant to all applications, there are also technique-specific controls that should be included to ensure that a protocol is working as expected. Detailed explanations of these controls can be found in each of our Applications Guides.