Ryan Hamnett, PhD | 30th September 2024

In addition to ensuring that an antibody has been sufficiently validated as being specific, there are a number of aspects that must be taken into account when choosing an antibody for an experiment. The following considerations are applicable to most if not all of the common antibody-based applications.

For information on how to choose a secondary antibody, see our dedicated Secondary Antibody Selection Guide .

Primary antibodies will recognize a protein only from certain species. Usually this will be the species that the immunizing antigen was originally from as well as closely related species. An antibody should be chosen that has been validated as working in specific species, which is always indicated on the product datasheet.

If a species is not listed, particularly for a non-model organism, an antibody may still work for it, it just has not been tested yet. The key determinant of this is how similar the epitope sequence is between species. Highly conserved proteins may be recognizable in organisms that are further away on the evolutionary tree.

Not all antibodies work with all applications. This is usually due to differences in sample processing between the techniques, resulting in the antigens being in different forms or having different levels of accessibility. For example, samples for IHC are fixed, meaning the proteins are held in their endogenous states, whereas samples for western blots are denatured, which will destroy some epitopes but make others accessible.

Fixation has its own issues, however. Overfixation can mask epitopes, preventing the antibody from recognizing them. Making the epitope accessible again may require antigen retrieval or use of an alternative fixative.

The effect of these considerations is that a chosen antibody should be validated to work in its intended application. Sometimes an antibody has not been tested for a particular application. In these instances, an antibody that has been validated for a similar application should be chosen for the highest chance of success. For instance, an antibody that has been validated for IHC or ELISA might work for co-IP, because all three techniques look at proteins in their native conformation.

Note that there can be application-specific considerations though. In the previous example, an antibody may be able to capture the target in co-IP, but it may bind to an important site that interferes with protein-protein interactions. Similarly, in sandwich ELISAs, at least two antibodies are needed that recognize different epitopes and do not interfere with each other’s binding.

As described earlier, the clonality of an antibody reflects how the antibody was produced and how many epitopes it targets (see Polyclonal and Monoclonal Antibodies: Production and Purification). Though both monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies will work for all applications, one may be more suited to a specific application or a specific antigen than the other.

Polyclonal antibodies are sometimes preferred when the target is known to be low abundance, because more epitopes targeted means more binding to the target and therefore greater signal amplification.

Monoclonal antibodies are more specific and their binding site is known. This makes them highly useful for techniques requiring multiple antibodies, such as sandwich ELISAs, which require a matched pair of antibodies that bind to different epitopes. Monoclonal antibodies also promise more consistency between lots, making them the preferred choice if the same experiment will be run repeatedly over a long period of time.

The region of the protein that an antibody binds to may be important for some experiments. For instance, when targeting a protein for live cell FACS, the antibody needs to target the extracellular domain because it will not be able to permeate the plasma membrane. Epitope location may also be relevant when investigating alternative splice forms or validating the success of a conditional knockout model. In both of these cases, sometimes only a single exon has been removed compared to the canonical protein. An antibody that binds to an unaffected region may therefore be uninformative.

The epitope is determined by the immunogen (the antigen used to immunize the host animal). Sometimes the immunogen is a full length protein, other times it is only part of the protein. Immunogen details can usually be found on the product datasheet.

Antibodies are usually stored in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), as well as carrier proteins such as bovine serum albumin (BSA), and preservatives such as glycerol and sodium azide. These additives help to maintain antibody stability and prevent bacterial growth, thereby preserving antibody activity.

However, additives can interfere with some experimental setups. BSA can compete with the antibody when conjugating it to fluorophores or enzymes, reducing the conjugation efficiency. Sodium azide is toxic to cells, which limits its use when cell viability is an important factor. Therefore, for experiments requiring primary antibody conjugation or live cells, antibodies without carriers or preservatives are preferred.

The optimal concentration for primary antibodies will depend on a number of factors, including the affinity and specificity of the antibody, the application, the tissue or cell sample, equipment sensitivity, and application-specific conditions such as fixative or buffer formulations.

Most antibody datasheets will provide a recommended dilution range, usually within 1 – 25 μg/ml. A datasheet may give recommended concentrations to use relative to a master stock, such as 1:500, instead of absolute concentrations in μg/mL. This is particularly common for polyclonal antibodies, where the exact antibody concentration is not known.

A higher concentration will give stronger signal, but more background due to non-specific binding, while a lower concentration will result in lower signal and background. The important factor is the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which will also vary with different concentrations.

The optimal antibody concentration can be determined for a given application by performing a dilution series or antibody titration. Essentially this involves testing the antibody over several different concentrations on multiple sections from a single sample to determine which concentration gives the best SNR. For example, if a datasheet recommends using an antibody at 1:1000, a dilution series may test concentrations of 1:500, 1:1000, 1:2000, 1:4000 and 1:8000.

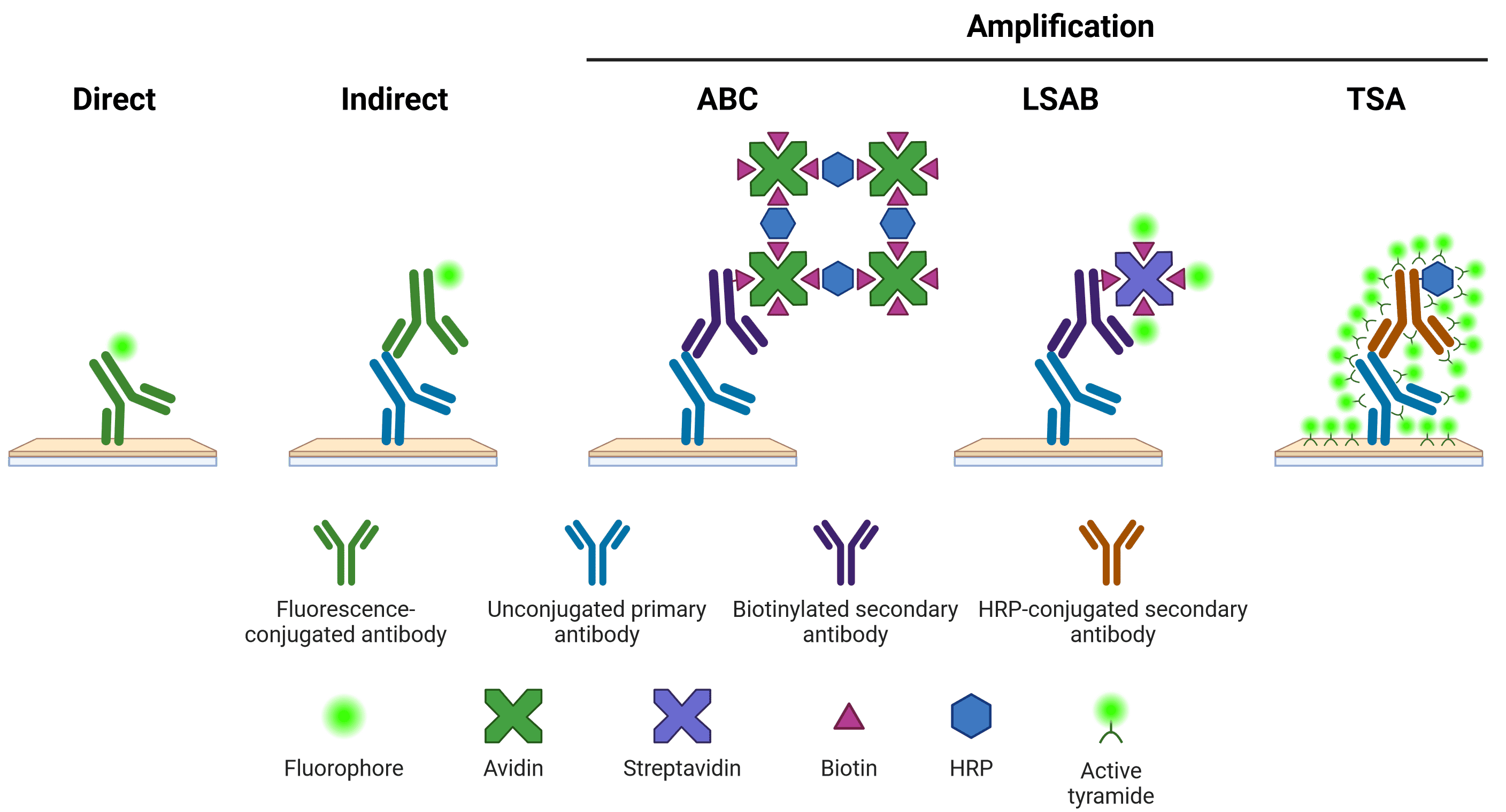

Once an antibody has bound to its target protein, it needs to be detected in some way. This detection can be either direct or indirect (Figure 1). For direct detection, the antibody that binds to the antigen is conjugated to a fluorophore or enzyme. For indirect detection, the antibody that binds to the antigen (the primary antibody) is in turn bound by another antibody (the secondary antibody), which has been conjugated to a fluorophore or enzyme. The secondary antibody has been raised against the primary antibody's host species.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of different methods of target detection Methods of amplification include the avidin-biotin complex (ABC), labeled streptavidin-biotin (LSAB) and tyramide signal amplification (TSA) systems. Created using BioRender.

Indirect detection systems offer superior signal intensity, as multiple secondary antibodies can bind to one primary antibody. Secondary antibodies also offer greater flexibility, able to recognize many different primary antibodies from the same host, which may not be available pre-conjugated from commercial sources. However, secondary antibodies can also result in a higher background signal and therefore require optimization.

On top of indirect detection, an additional amplification step can be performed (Figure 1). Amplification steps often use secondary antibodies that have been conjugated to biotin, which in turn is bound by multiple avidin or streptavidin molecules. Avidin and streptavidin can be conjugated to multiple fluorophores or enzymes, greatly increasing the amount of signal emanating from a single secondary antibody.

The tyramide signal amplification (TSA) system is another way of increasing signal that relies on the enzyme horseradish peroxidase (HRP). HRP catalyzes the conversion of inactive, fluorescently labeled tyramide to a reactive radical, which then binds nearby tyrosine residues, illuminating the area near to the antibody binding site.

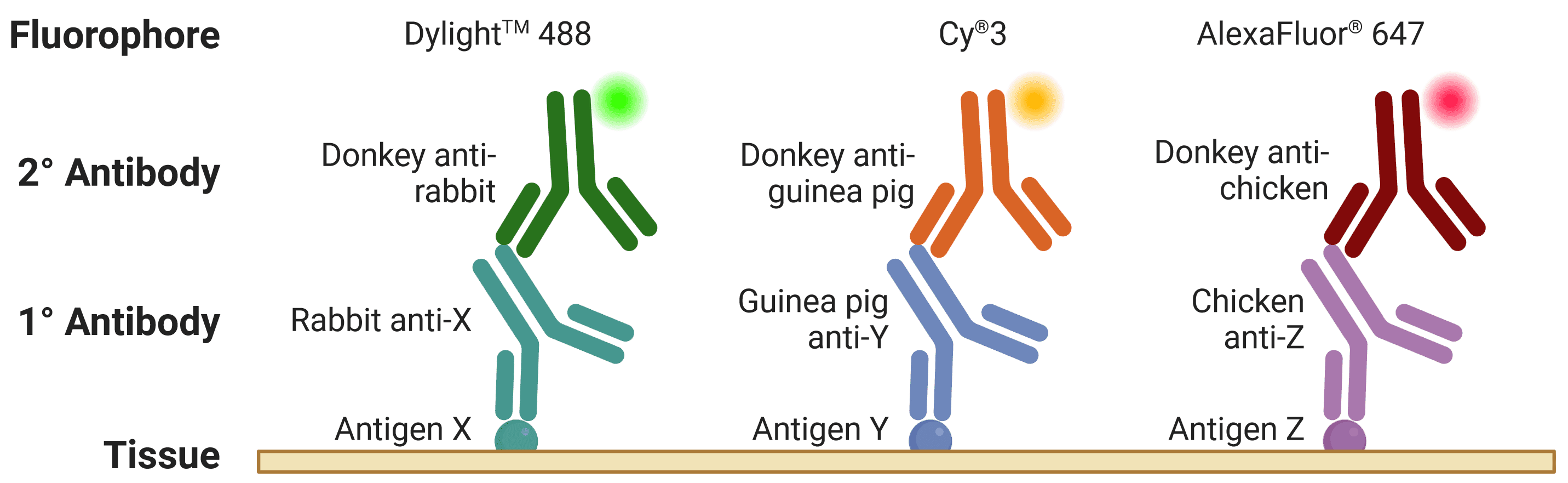

The host is the species of animal an antibody was raised in. This is particularly important to know when using indirect detection methods, because secondary antibodies are directed against the host species of primary antibodies, as illustrated in Figure 2. Where possible, primary antibodies should not be from the same host species as the sample under investigation, such as using mouse primary antibodies on mouse tissue, because secondary antibodies (e.g. goat anti-mouse) will recognize not only the primary antibody but other endogenous proteins too.

Figure 2: Multiplexed staining with IHC. Multiple antigens can be detected simultaneously by using primary antibodies raised in different species. Secondary antibodies will then recognize primary antibodies from a given species, and can be resolved under a fluorescence microscope through conjugation to spectrally distinct fluorophores. Created using BioRender.

When multiplexing, such as detecting multiple proteins in IHC, if two primary antibodies are used from the same host species, the secondary antibodies will recognize both primary antibodies, making them impossible to distinguish during visualization. This is referred to as cross-reactivity.

This is further complicated by secondary antibodies recognizing other secondary antibodies, which is a risk when using primary antibodies raised in goat (e.g. donkey anti-goat secondary antibodies will bind both primary and secondary antibodies raised in goat).

As outlined in Antibody Formats, antibodies can take numerous different forms depending on how they were engineered. Most commercial antibodies will be available in the conventional IgG or IgM format, particularly polyclonals. For recombinant antibodies, the choice of format will depend on the number of targets (e.g. if multivalency is necessary), tissue penetration, stability, and pharmacokinetic properties.

Using a conjugated primary antibody removes the need for a secondary antibody step. It is therefore quicker, usually results in less background signal, and minimizes cross-reactivity where secondary antibodies, allowing for multiplexed experiments using multiple primary antibodies from the same host. However, they do not provide any method of signal amplification, meaning the target must be relatively abundant.

We offer a large number of antibody conjugation kits to conjugate antibodies to one of a range of fluorophores and enzymes.

Most antibodies should retain their binding activity for years if handled and stored properly, instructions for which can be found on the datasheet.

Generally, antibodies are shipped on ice if they are already in solution, but can be shipped at room temperature if they are lyophilized (freeze-dried). If it is lyophilized, it will need to be reconstituted before use, usually in the volume of water or PBS indicated on the datasheet.

Freezing Antibodies

Storing an antibody at 4°C is acceptable for 1 to 2 weeks, but it should be aliquoted into single-use low-protein-binding tubes and frozen for long term storage. Freezing at -20°C or -80°C is will adequately preserve the antibody; there is no major advantage to storing them at -80°C. Frost-free freezers should be avoided, as these cycle through thawing and freezing to prevent frost accumulation, which will damage the antibody.

Aliquoting reduces the potential for contamination of stocks and reduces the need for repeated freezing and thawing, which would otherwise damage the integrity of the antibody or cause it to aggregate. Aliquot size should be matched to the amount of antibody typically used in an experiment – a 50 μl aliquot will not be fully used if each experiment only requires 10 μl. Nonetheless, aliquots should not be less than 10 μl, because smaller aliquots suffer from evaporation and adsorption of the antibody to the vial.

Conjugated Antibodies

Conjugated antibodies can have more complex storage conditions due to the nature of their conjugates, and datasheet instructions should be followed carefully.

Conjugates, particularly fluorophores, are sensitive to light, and so vials should be kept in the dark (e.g. wrapped in foil) to protect them.

Enzyme conjugates should generally not be frozen as this will reduce enzymatic activity. Some antibody conjugates contain a cryoprotectant and been validated for long term storage at -20°C, which will be indicated on the datasheet. Otherwise, they should be kept at 4°C.

Conjugated antibodies are often secondary antibodies, which can often be kept at 4°C for many months while retaining their activity.

Additives

Sodium azide can be added to antibodies at a concentration of 0.02% (w/v) to prevent bacterial contamination. The datasheet will indicate whether sodium azide has already been added to an antibody.

However, sodium azide should be avoided when an antibody is intended for us with live cells, as azide is toxic to cells. Sodium azide also inhibits HRP activity, so it should not be added to HRP-conjugates.

Glycerol is a cryoprotectant that lowers the freezing temperature to below -20°C, meaning antibodies can be stored in the freezer without freezing. This retains the benefits of inhibiting bacterial growth and activity, but avoids the potential for freeze-thaw damage. Glycerol will still freeze at -80°C though, so glycerol stocks should be kept at -20°C. Glycerol should be added to a final concentration of 50%, but some antibodies may not be stable in these conditions, so the product datasheet should be consulted.