Ryan Hamnett, PhD | 30th September 2024

Understanding the structure of an immunoglobulin is essential to understand how antibodies carry out their roles in the immune system. While antibodies are most commonly depicted as having a classic Y-shaped structure with well-defined functional domains, mammalian antibodies naturally occur in a number of different conformations termed isotypes, which fulfill distinct jobs in the immune system.

Scientists have engineered novel antibody conformations comprising specific domains to alter their properties such as their size, the number of different targets they recognize, stability, and pharmacokinetics. These different antibody formats are adapted for specific applications in medicine and research.

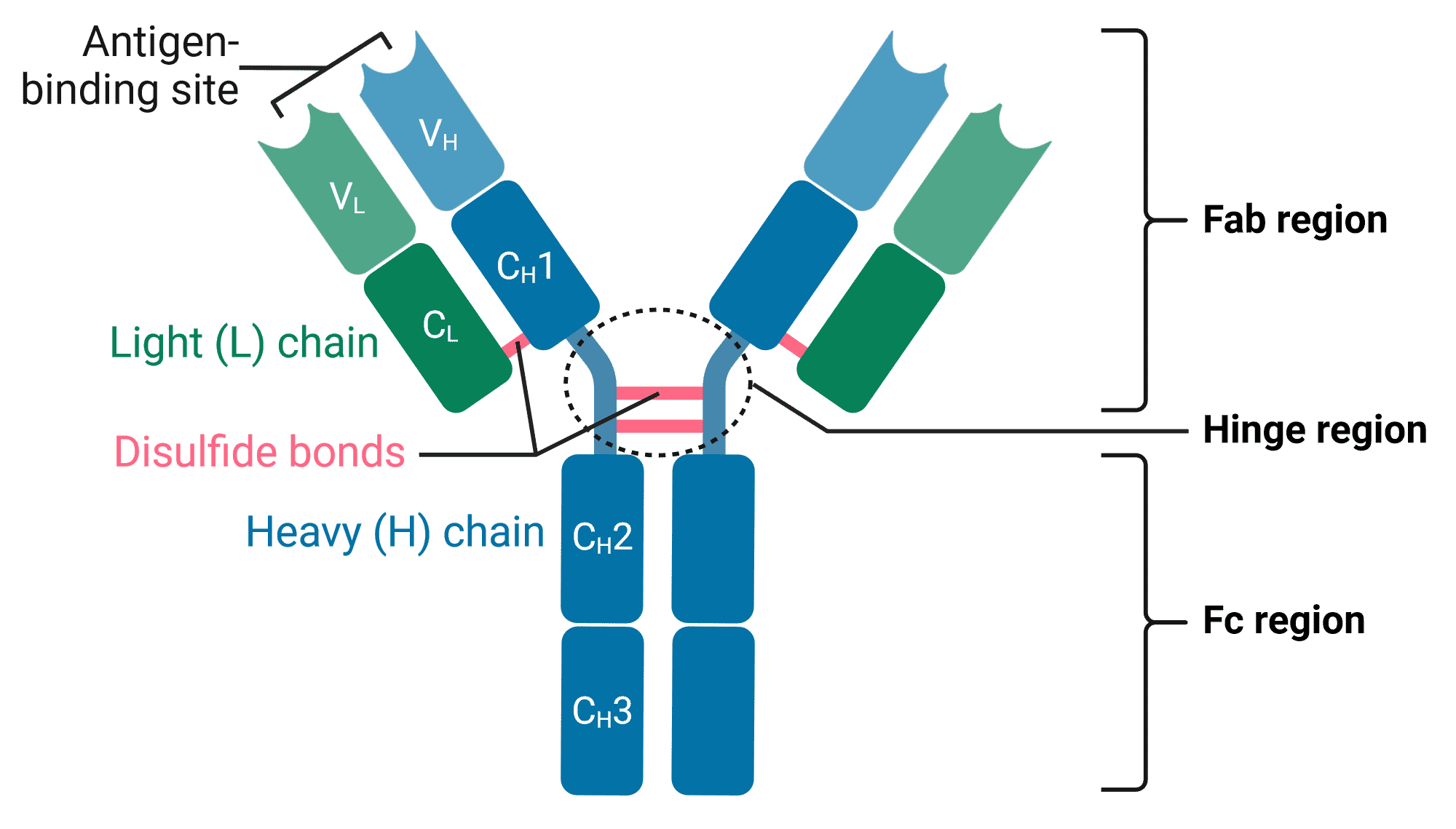

Antibodies are Y-shaped proteins comprising four polypeptide chains: two identical heavy (H) chains and two identical light (L) chains (Figure 1). The arms of the Y end in the variable (V) region, which is responsible for binding to antigens, hence the arms are also referred to as the fragment antigen-binding (Fab) region. In contrast, the stem of the Y is called the constant (C) region or fragment crystallizable (Fc) region, which can be bound by immune cells.

Figure 1: Structure of an antibody (IgG).C: Constant region; V: Variable region. Created using BioRender.

Heavy Chain

Heavy chains define the antibody isotype. In mammals, there are five different types of heavy chain: α, δ, ε, γ and μ, which define IgA, IgD, IgE, IgG, and IgM isotypes respectively. These different chains have different amino acid compositions and lengths, resulting in different antibody structures and ultimately distinct functions.

The heavy chains of an antibody form the Fc region, and are linked with light chains to form the Fab regions. Heavy chains have constant (CH) regions at their C-terminus, and variable (VH) regions at their N-terminus. This constant region is identical across antibodies of the same isotype.

Light Chain

There are only two types of light chain in mammals: lambda (λ) and kappa (κ). These chains have minor differences in amino acid sequences, as well as slightly different structural and biophysical properties.

Light chains are only found in the Fab regions, and the two light chains in any given antibody are identical to each other. As in heavy chains, there are constant (CL) and variable (VL) regions in light chains at the C- and N-termini, respectively.

Camelids are unique among mammals in being able to form antibodies that lack light chains. The N-terminal domain of these heavy chain antibodies can be used in isolation and are called nanobodies.

Fab Region

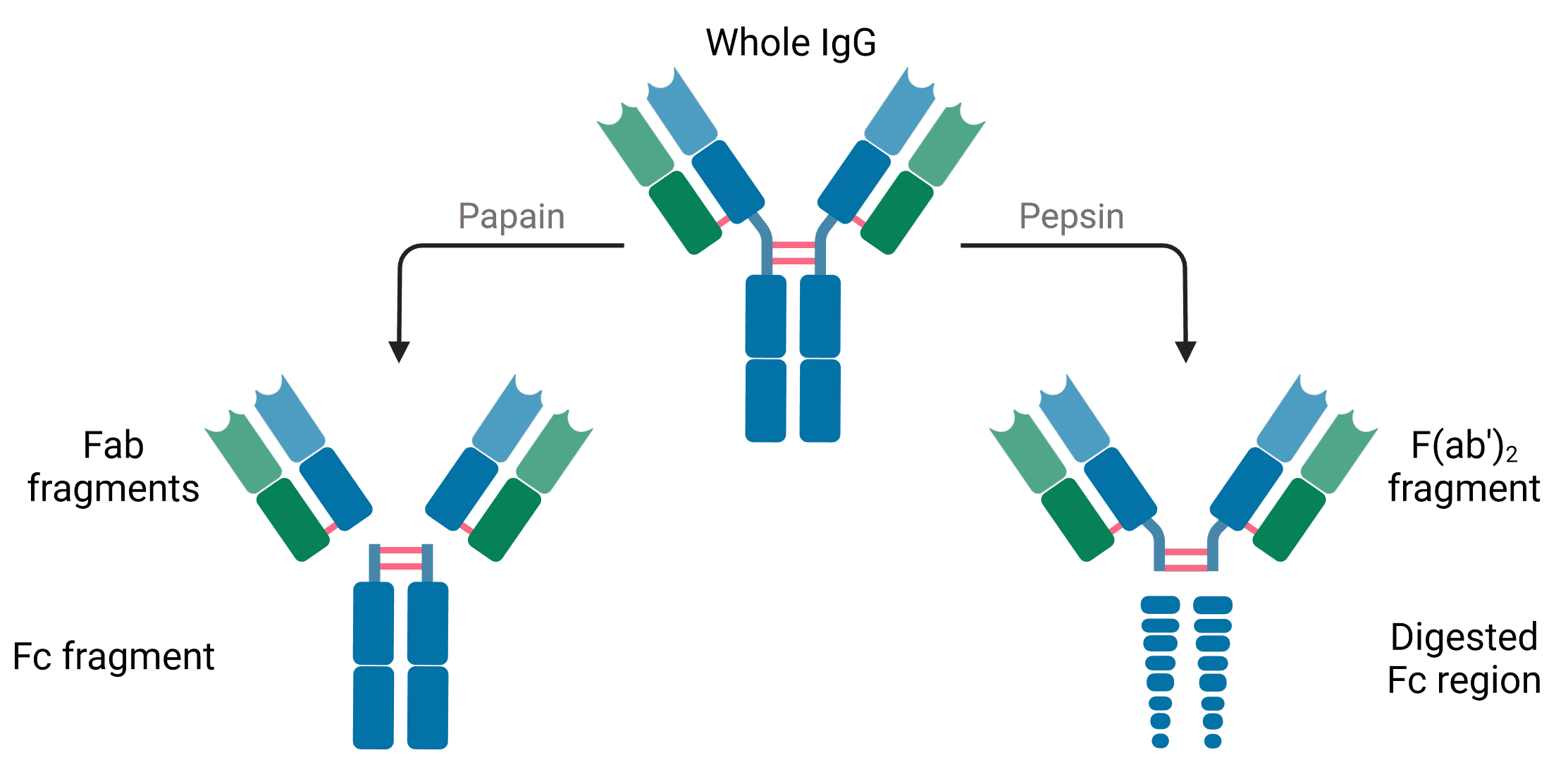

Antibodies subjected to treatment with the enzyme papain are cleaved into two fragments: the Fab and Fc regions (Figure 2). Papain cleaves antibodies above the disulfide bonds that hold the two heavy chains together in the hinge region, meaning a single antibody produces two Fab regions, each containing one light chain and part of one heavy chain. The N-terminal domains of the H and L chains are called the variable regions (V regions).

Figure 2: Antibody fragments generated by enzymatic digestion with papain or pepsin. Created using BioRender.

While the Fab regions contain the variable, antigen-binding region of the antibody, ‘Fab’ is not quite synonymous with ‘variable’. This is because some of the Fab domain also contains sequences that are constant across different antibodies of the same isotype. The variable domains represent only the tips of the Fab regions.

Digestion with pepsin cleaves at a slightly different position, leaving the hinge intact and the two Fab regions still attached in the center, hence the name F(ab’)2.

Fab fragments are useful in experiments because they are smaller, facilitating cell penetration, and because they will not be bound by immune cells, which usually recognize the Fc region (see Antibody Format).

Fc Region

The Fc region contains only the C-terminals of heavy chains, and is entirely constant across antibodies of the same isotype. Fc stands for “fragment crystallizable,” because its well-conserved amino acid sequence allows this fragment to crystallize after isolation with papain treatment (Figure 2). Many immune cells contain Fc receptors on their surface that allow them to bind to antibodies that are bound to pathogens or infected cells, stimulating their phagocytosis or destruction.

The Fc region of antibodies serves several useful purposes in experiments. Enzymes and fluorophores can be covalently linked to the Fc region for visualization in ELISA, immunohistochemistry, western blot and flow cytometry. In immunoprecipitation, the Fc region can be captured onto beads by Protein A or G, which specifically bind to the constant region of antibodies. Fc fragments are sometimes used as a blocking component to block the Fc receptors on immune cells, which can otherwise interfere in some experiments such as flow cytometry.

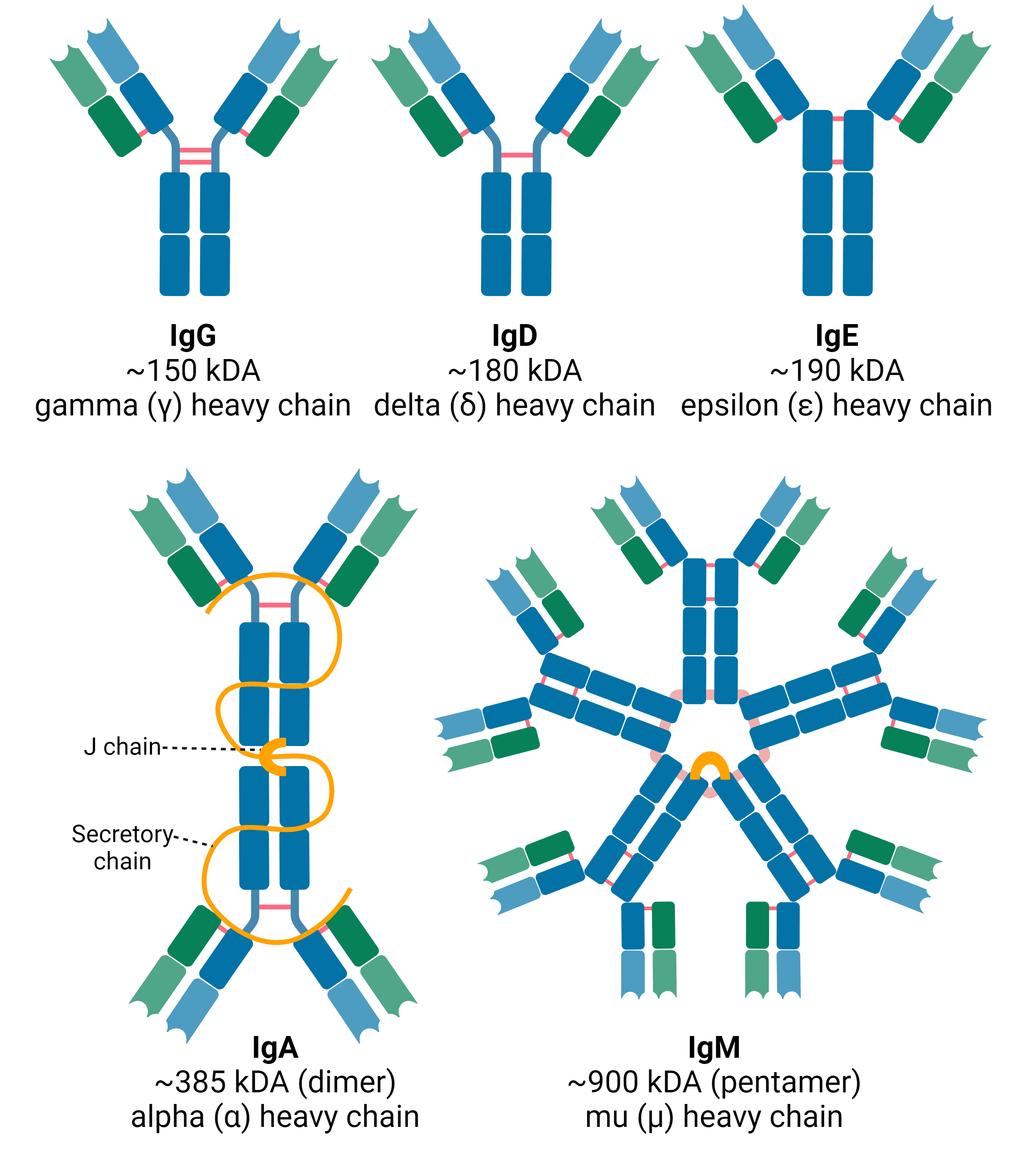

The isotype of an immunoglobulin molecule refers to its structure and the identity of its heavy chain (Figure 3). In mammals, there are five different isotypes: IgA, IgD, IgE, IgG and IgM, defined by the presence of the α, δ, ε, γ and μ heavy chains, respectively.

In the immune system, antibody isotypes have different functions and are prominent at different stages of the immune response.

Figure 3: Antibody isotypes in mammals. IgG, IgD and IgE have only minor differences in structure and tend to exist as monomers. IgA can exist as both monomer and dimer. As a dimer found in secretions, it has two additional protein chains, termed the joining (J) chain and the secretory chain. IgM also contains the J chain, and usually occurs as a pentamer. Created using BioRender.

IgG

IgG is the most abundant antibody in the blood of mammals, representing 70-85% of the total Ig pool, though it can also be found in tissues. It is the primary component of the secondary immune response, which occurs when the immune system is exposed to an antigen that it has already encountered at least once. The long half-life of IgG means that it can mediate immunity to pathogens for months or years.

IgG has several important functions, including:

IgM

IgM represents 5-10% of the total Ig pool. It is important for the primary immune response that occurs when encountering an antigen for the first time, and can also activate the classical pathway of the complement system by binding C1. Its large, pentameric structure means that it tends to be restricted to the blood.

IgA

IgA accounts for 5-15% of the total Ig pool and is present as either a monomer or a dimer. As a dimer it contains additional polypeptide chains that are important to its structure and function: the joining (J) chain and the secretory chain (found only in secretions). IgA is found in both serum and mucosal secretions such as saliva, tears, milk and mucus, from which it protects mucosal membranes.

IgE

IgE is synthesized within plasma B cells and interacts with basophils and mast cells, with very little IgE found in circulation. Though IgE is thought to be involved in the immune response to parasites, it is best known for its role in hypersensitivity to allergens, such as in asthma, sinusitis, food allergies, and anaphylaxis in response to drugs.

IgD

IgD is only approximately 1% of the total Ig pool, typically found on the surface of B-lymphocytes alongside IgM. IgD is the least well characterized of the mammalian isotypes, but it is highly evolutionarily conserved and appears to be a marker of B cell activation.

IgY

IgY is the major antibody isotype in birds and reptile serum as well as egg yolk. It is analogous to the mammalian IgG and performs similar functions, though it does not activate the complement system. It is structurally distinct from IgG and is not recognized by antibodies raised against IgG.

Isotype Controls

When staining tissue or cells with an antibody, the antibody may bind to molecules other than the target molecule, such as Fc receptors on immune cells. This non-specific binding or off-target binding will produce a background signal that can reduce the signal-to-noise ratio and interfere with interpretation of results. To identify what portion of the signal is due to specific vs non-specific binding, an isotype control antibody is used.

Isotype control antibodies differ from the primary antibodies only in the specificity for the antigen. This means they will otherwise bear all of the same properties as the primary antibody, such as: host species, isotype, and conjugation. Typically isotype controls do not bind to any antigen in the sample, meaning that any observed signal is due to non-specific interactions and can be excluded from analysis.

Isotype controls are particularly important when performing techniques that involve cells with endogenous Fc receptors and the risk of background signal is high, such as flow cytometry.

More information can be found on our Isotype Controls page.

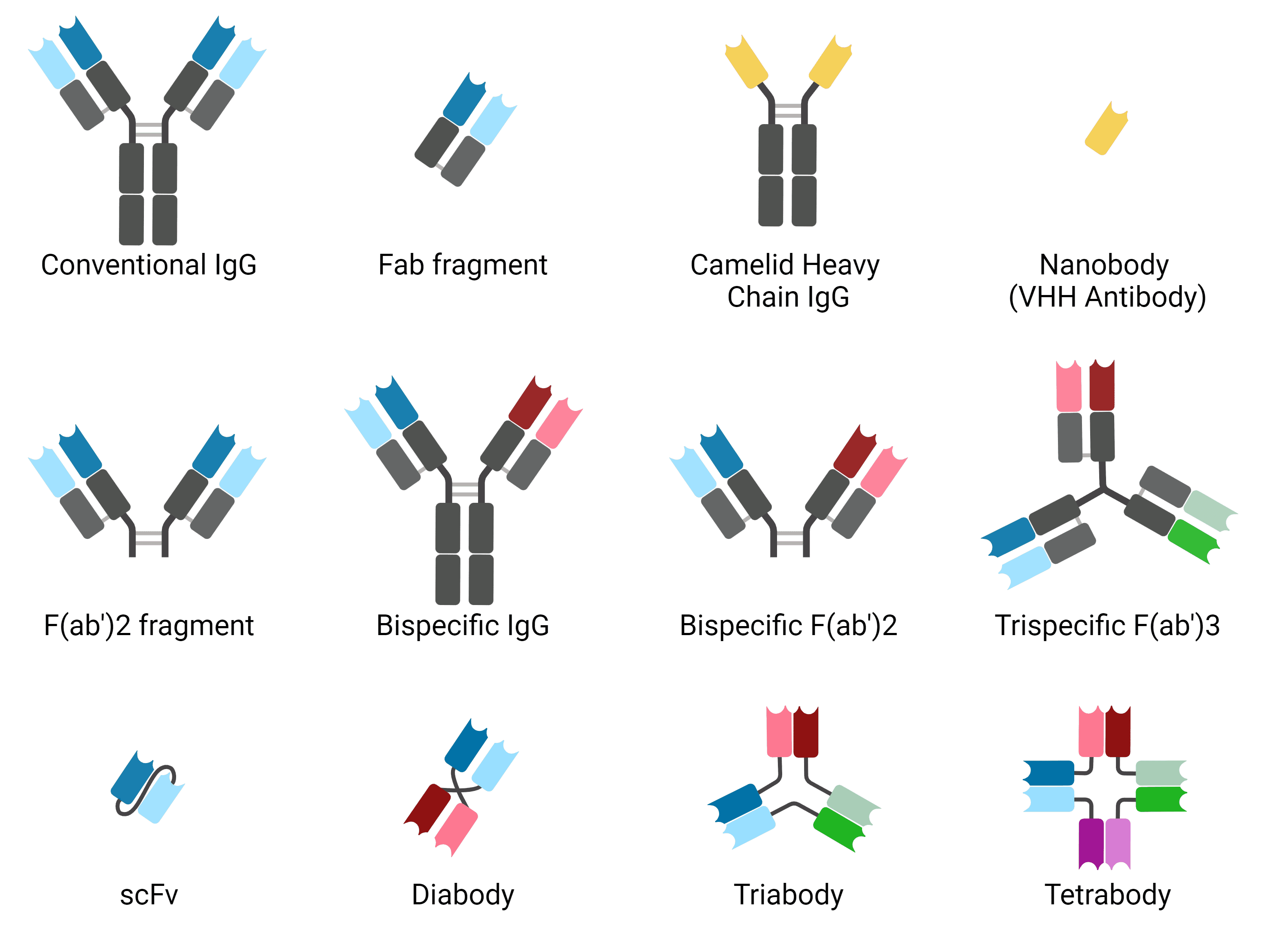

The antibody format refers to the different structural configuration of antibodies. The classic Y-shaped IgG is one antibody format, but several others have been engineered by scientists to increase tissue penetration, reduce non-specific binding, alter clearance times from circulation, and be more amenable to different methods of production. Some, such as nanobodies, exhibit some advantages of engineered antibody formats but occur naturally. Figure 4 and the following list describes the most common antibody formats.

Figure 4: Common antibody formats. Created using BioRender.

Full-Length Antibodies

These are conventional Y-shaped antibodies, consisting of two full length heavy and light chains. They have two binding sites and can be bound in their constant region by immune cells.

Fragment Antigen-Binding (Fab)

Fab fragments represent one arm of a full-length antibody. They have one constant and one variable domain of heavy and light chains, and a single antigen-binding site. They can be made recombinantly or by enzymatic cleavage with papain. Their small size means that they penetrate tissue more effectively. They lack the Fc region, and so do not activate immune cells or the complement system.

F(ab')2 Fragments

F(ab')2 fragments are made by enzymatic cleavage with the enzyme pepsin, which cleaves below the hinge region and so leaves the two arms of the antibody still connected. The still lack the Fc region but have two antigen-binding sites.

Nanobodies

Nanobodies are single domain antibodies derived from camelid antibodies consisting only of the variable domain of the heavy chain, and so are sometimes called VHH antibodies. They have similar binding affinities to conventional antibodies, but are ~90% smaller, aiding with tissue penetration. They are typically produced recombinantly and so are highly consistent. Single domain antibodies can also be produced from shark immunoglobulins (immunoglobulin new antigen receptor, IgNAR), called VNAR).

Bispecific Antibodies

Bispecific antibodies have been engineered so that the two antigen binding sites of a full-length antibody recognize and bind to distinct epitopes. These can be useful in cancer therapies, bringing together tumor cells and immune cells by binding to both.

Single-Chain Variable Fragment (scFv)

scFvs are even smaller than Fab fragments, comprising just the variable regions of the heavy and light chains. They are connected by a short peptide linker. scFvs can be more easily made in E. coli as recombinant proteins, and their small size gives them even better tissue penetration than Fab fragments, though they are less stable.

Multivalent Antibodies

Reducing the linker length in scFv can disturb the intramolecular interactions necessary to create an scFv, but by doing so allow scFvs to naturally mulimerize to create diabodies, triabodies and tetrabodies. These have valencies of two, three and four respectively, which can either be for the same target to increase affinity, or multiple targets. Other, more complex architectures for multivalent antibodies also exist.

Chimeric and Humanized Antibodies

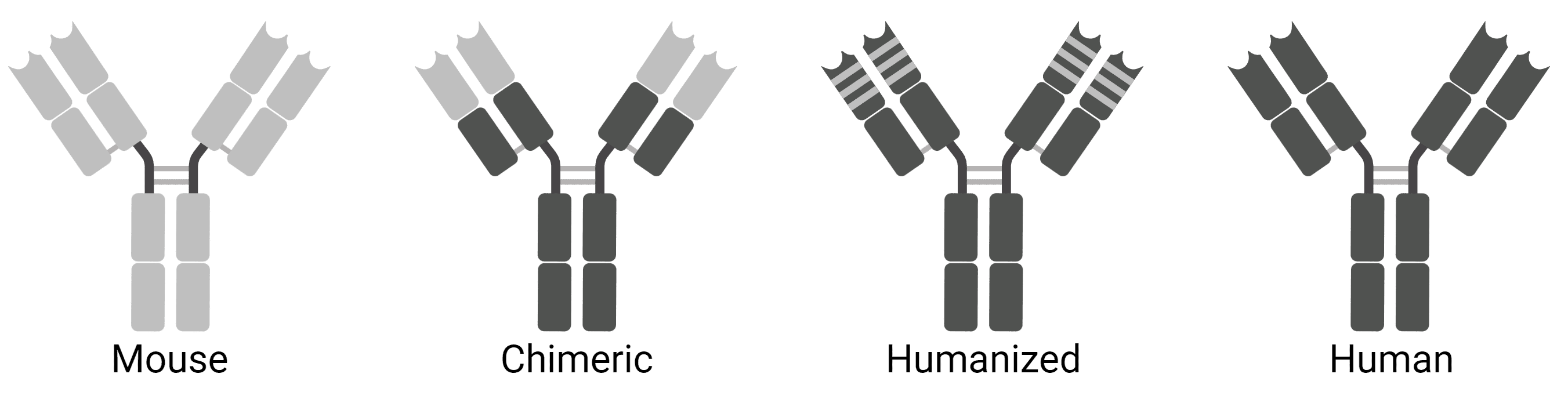

Chimeric antibodies are usually mouse antibodies that have been genetically engineered to replace the mouse constant region with a human constant region (Figure 5). Thus, the antibody binding site remains unaffected, but the antibody will be less likely to be recognized as a foreign protein by a human’s immune system. This is useful for using existing mouse antibodies as therapies. Humanized antibodies take this one step further, where most of the variable region also comes from human antibodies, retaining only the mouse antigen binding site.

Figure 5: Chimeric and humanized antibodies.