Ryan Hamnett, PhD | 4th February 2025

Astrocytes, also known as astroglia, are a type of glial cell found within the central nervous system. Named for their star-like appearance first observed by Ramón y Cajal and others using the Golgi stain, astrocytes are key components of neural networks, essential for maintaining neuronal homeostasis and function.

Astrocytes are frequently defined by molecular markers using antibodies in techniques such as immunohistochemistry. Using protein markers to highlight astrocytes allows researchers to establish if a protein of interest is expressed in astrocytes, and monitor changes to astrocyte populations in disease. The most commonly used astrocyte markers are GFAP, S100β and ALDH1L1, though most markers show heterogeneous expression patterns or fail to mark at least some astrocytes, meaning that multiple may need to be used to cover all astrocytes.1,2

This guide will explore the most commonly used markers of astrocytes, suitable for the majority of experiments. For an extensive review of astrocyte markers, see Jurga et al., 2021,3 as well as single cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) papers, which can reveal markers of astrocytic subpopulations.1

While astrocytes are recognized as a diverse and heterogeneous population,4 some common criteria can be applied to distinguish them from neurons and other glia.5 Among others, these include: non-excitability, negative membrane potential determined by the transmembrane K+ gradient, uptake of the neurotransmitters GABA and glutamate by specific transporters, processes surrounding synapses and blood vessels, and gap junctions to connect multiple cells together.5 Many of these features enable astrocytes to fulfill numerous functions in the CNS, including:

Astrocytes have a well-established role at the tripartite synapse, which consists of pre- and post-synaptic terminals and an astrocytic process (Figure 1). Here they are typically involved in taking in excess neurotransmitter to prevent overstimulation of the recipient neuron, and recycling components back to the pre-synaptic neuron to prepare for synaptic release. Membrane receptors on the astrocyte plasma membrane can be activated by neurotransmitters released into the synaptic cleft, meaning they can sense neuronal activity and respond with appropriate modulation.6 Disruption of astrocytic activity at the synapse, such as by loss of the growth factor Norrin, results in significant neural network dysfunction.10

The ability of astrocytes to mediate inflammatory responses, repair neuronal architecture and ultimately influence the overall health of neurons means that they play active roles in the etiology and severity of numerous neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, schizophrenia, and brain injuries.9 Astrocytes can proliferate and employ common responses to diverse central nervous system (CNS) insults, making them attractive targets for therapeutics of neurodegenerative diseases and other disorders.9

Reactive Gliosis

Astrocytes are also the key mediators of reactive gliosis, also known as astrogliosis, characterized by remodeling of astrocyte morphology, altered gene expression, and functional changes in response to CNS insults (inflammation, infection, neurodegeneration, traumatic injuries). Reactive astrocytes are highly heterogeneous and can take on several different ‘activated’ states, such as A1 and A2 states, contributing to both pathology and repair. However, many have cautioned that the hypothesis of distinct activated phenotypes is overly simplistic, and that markers of cytotoxic or cytoprotective states are poorly developed and understood.3,11 Nevertheless, GFAP and other structural proteins such as vimentin and nestin are reliably increased in many pathological conditions.12

Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) is an intermediate filament found in astrocytes, the function of which is to provide mechanical support to astrocytes and the BBB.13 The most commonly used astrocyte marker, GFAP is also a reliable marker of reactive gliosis.14

As a marker, GFAP strongly labels astrocytic processes and, to a lesser extent, the cell body. This makes it ideal for studying astrocyte morphology and interactions with other cell types, but not as useful for monitoring astrocyte numbers, for which a nuclear or soma-restricted marker would be preferred. It is also worth noting that GFAP is not entirely exclusive to astrocytes. Other glia, such as Bergmann glia in the cerebellum and Müller glia in the retina, as well as tanycytes near the third ventricle, can also express GFAP, although these cell types are similar to astroglia.15

Other structural markers that can be used to identify astrocytes include vimentin, which is also found in fibroblasts, endothelial cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes; and nestin, which is common in progenitor cells and developing astrocytes but only weakly expressed in mature astrocytes.

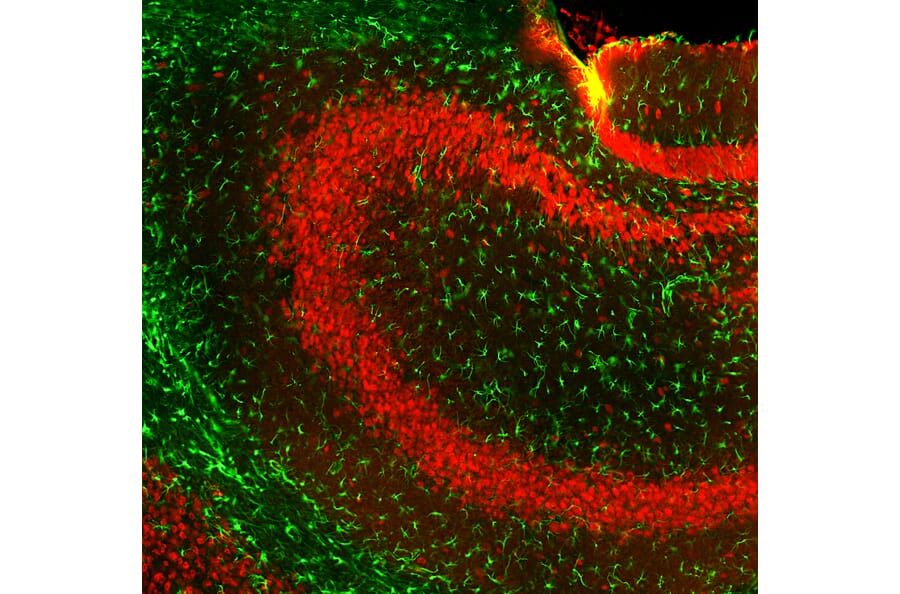

Figure 1: IHC of rat cerebellum co-stained with mouse anti-GFAP [5C10] (A85422) in green, and chicken anti-NF-L (A85451) in red.

Figure 2: IHC of mouse hippocampus co-stained with goat anti-GFAP (A270545) in green, and chicken anti-NeuN in red.

S100β is a Ca2+-binding protein involved in cell cycle regulation and cytoskeleton modification that has been extensively used as an astrocytic marker. S100β is found primarily in the cytoplasm and nucleus of astrocytes, showing strong co-expression with GFAP.16 Its nuclear localization makes it useful for counting astrocyte numbers,2 although S100β is not as restricted to astrocytes as other markers are: oligodendrocytes, NG2 glia and some neuron populations also express S100β.3,17

Figure 3: IHC of mouse brain stained with rabbit anti-S100 beta [ARC50351] (A307742) in red. Nuclei are marked with DAPI in blue.

Figure 4: IHC of FFPE human brain stained with monospecific mouse anti-S100 beta [S100B/4149] (A277782).

The folate enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member L1 (ALDH1L1) catalyzes the NADP+-dependent conversion of 10-formyltetrahydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate and NADPH in astrocytes, playing an important function in many cellular processes such as nucleotide biosynthesis.

ALDH1L1 has been shown to be a reliable marker of astrocytes, labeling the cytoplasm and co-expressing with other astrocyte markers such as GLT1, and showing upregulated expression in reactive astrocytes.17,18 ALDH1L1 labels the largest population of astrocytes in the human cortex and is now commonly used as a driver of genetic tools to manipulate astrocytes in mice.18,19

Figure 5: ICC/IF of E20 rat cortical neuron-glial cell cultures co-stained with mouse anti-ALDH1L1 [2E7] (A85314) in red and chicken anti-GFAP (A85307) in green. Nuclei are marked with DAPI in blue.

Figure 6: ICC/IF of E20 rat cortical neuron-glial cell cultures co-stained with mouse anti-ALDH1L1 [4A12] (A85315) in green and chicken anti-vimentin (A85421) in red. Nuclei are marked with DAPI in blue.

N-Myc downstream-regulated gene 2 (NDRG2) is a tumor suppressor gene and novel astrocytic marker, particularly for mature and non-reactive astrocytes.20 NDRG2 is found in the cytoplasm and processes of both protoplasmic and fibrous astrocytes, a classical division of astrocyte morphology, as well as Bergmann glia.20 NDRG2 has an advantage over GFAP as a marker of astrocytes because it is more uniformly expressed throughout the mammalian brain, marking astrocytes in some regions that have little GFAP immunoreactivity, though it is weaker than GFAP in white matter areas.2,20

While astrocytes mop up several neurotransmitters, including dopamine and norepinephrine, this functionality may be most important at glutamatergic synapses (Figure 7), given the risk of excitotoxicity if glutamate neurotransmission is insufficiently regulated. Regulation of glutamate is achieved through the excitatory amino acid transporters 1 and 2 (EAAT1 and EAAT2, also known as GLAST and GLT-1, respectively). These two Na+-dependent transporters are abundantly expressed in astrocytic processes, and show complementary expression profiles in astrocytes across the brain, including within specific regions such as the hippocampus.3,21 However, low levels of expression have been observed in multiple cell types in the CNS.21

Figure 7: Astrocytes at the tripartite synapse. Astrocytes take up excess glutamate from the synaptic cleft, convert it to glutamine, and recycle it to the presynaptic glutamatergic neuron terminal. Created using BioRender.

Glutamine synthetase catalyzes the amination of glutamate to glutamine (Figure 7). This is an important aspect of the glutamate-glutamine cycle: glutamate is released by glutamatergic neurons into the synaptic cleft to activate cognate receptors. Astrocytes take up excess glutamate and convert it to glutamine before transporting the glutamine back to the neurons for conversion to glutamate and loading into synaptic vesicles. Glutamine synthetase is therefore a reliable marker of astrocytes, and has even been suggested by some to be the most general astrocyte marker.22 However, some non-astrocytic glia express low levels of glutamine synthetase in their soma, while some neurons have been shown to express it during neurodegenerative conditions.

Aquaporin 4 (AQP4) maintains water homeostasis throughout the brain and is localized on the endfeet of astrocytic processes at the BBB. As a marker, AQP4 is expressed in the majority of astrocytes, and can be used to stain the plasma membrane.1,23 AQP4 is not expressed in oligodendrocytes, but is found in Bergmann glia.

Figure 8: IHC of mouse brain stained with rabbit anti-AQP4 [ARC54345] (A80530). Nuclei are marked with DAPI in blue.

Figure 9: IHC of rat brain stained with rabbit anti-AQP4 (A14238). Nuclei are marked with DAPI in blue.

SOX9 and Other Transcription Factors

Numerous transcription factors are involved in the development of astrocyte subpopulations. Despite astrocytic heterogeneity, SOX9 is a common transcription factor found in essentially all astrocytes, responsible for astrocyte specification.1,24 Having been identified and characterized during a search for a nuclear astrocyte marker, SOX9 was found to be restricted to astrocytes in all regions of the brain other than ependymal cells and in the neurogenic regions, because SOX9 is also expressed in neural progenitor cells.24 Like GFAP, SOX9 is upregulated in reactive astrocytes.24

The transcription factor Id3 has also been recently identified in determining astrocytic fate, though it is not yet established as a marker.1,25

Other transcription factors involved in defining specific subpopulations of astrocytes include Nkx2-1, which regulates the expression of GFAP, although it is also found in many neurons. Nkx3-1 and Nkx6-1 were also identified as marking regional populations of astrocytes within the olfactory bulb and brainstem, respectively.26

Metabolic Markers

Astrocytes are important regulators of energy stores and energy metabolism in the brain. To facilitate this role, astrocytes are uniquely positioned to synthesize glycogen from glucose thanks to the expression of glycogen phosphorylase (GP), glycogen synthase (GS) and the glucose transporter GLUT1. Glycogen in the CNS is used as an emergency energy reserve, though there is evidence for its use in normal physiology as well.

GLUT1 allows selective transport of glucose from the blood vessels that astrocytes are in close contact with, and so is found in astrocytes surrounding blood vessels, particularly in gray matter.27

GS endows astrocytes with the ability to generate glycogen from excess glucose to be used at a later time, while GP catalyzes glycogen degradation for use. Expression of GS and GP appears to be specific to astrocytes throughout the brain, although some dorsal root ganglion (DRG) and spinal cord neurons show weak expression of GP.28

![IHC of rat cerebellum using anti-GFAP [5C10] (A85422)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/85/A85422_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC of mouse brain stained with rabbit anti-S100 beta antibody [ARC50351] (A307742)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/307/A307742_4.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC of FFPE human brain using anti-S100 beta [S100B/4149] (A277782)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/277/A277782_2.jpg?profile=product_image)

![ICC/IF of E20 rat cortical neuron-glial cell cultures using anti-ALDH1L1 [2E7] Antibody (A91949)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/85/A85314_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![ICC/IF of E20 rat cortical neuron-glial cell cultures using anti-ALDH1L1 [4A12] Antibody (A85315)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/85/A85315_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC of mouse brain using anti-AQP4 [ARC54345] Antibody (A80530)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/80/A80530_5.jpg?profile=product_image)