Kai Boon Tan, PhD | 29th August 2025

Schwann cells are the major glial cells of the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Derived from neural crest cells (NCCs), Schwann cells are responsible for ensheathing and myelinating axons, and facilitating axon survival and regeneration, while exhibiting remarkable phenotypic plasticity upon injury.

The development, maturation, and functional states of Schwann cells in health and neuropathies can be characterized by using key molecular markers. Schwann cell markers can be used in neuroscience research to:

| Schwann Cell stages | Key Marker(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Pan-Schwann cell lineage progression | SOX9 and SOX10 | Transcription factors involved in Schwann cell development by specifying glial lineage identity throughout, from neural crest cells to myelinating and non-myelinating Schwann cells. |

| Neural crest cells (NCCs) | TFAP2A, ETV5, and PAX3 | Markers for NCCs committed to glial fate. |

| Schwann cell precursors (SCPs) | TFAP2A, PAX3, SOX2 and EGR1 | Markers that contribute to the regulatory network governing the differentiation from NCCs into SCPs. |

| Boundary-cap cells | EGR2, FOXD3, TFAP2A and PAX3 | Transcription factors that orchestrate boundary cap cell specification, multipotency maintenance, and spinal cord barrier integrity. |

| Immature Schwann cells (iSC) | TFAP2A | Transcription factor responsible for cell fate specification and lineage progression towards myelinating Schwann cells, while preventing premature differentiation. |

| Pro-myelinating Schwann cells | JUN, POU3F1 (or OCT6), and YY1 | Transcription factors that collectively poise myelination genes in the pro-myelinating stage to allow Schwann cells to prepare for myelination. |

| Myelinating Schwann cells | POU3F1, YY1, NFATC4, and EGR2 (or KROX20) | These transcription factors cooperatively orchestrate the activation of myelin genes and lipid synthesis, driving the formation and maintenance of the compact myelin sheath in Schwann cells. |

| Non-myelinating (Remak) Schwann cells | SOX2, JUN, PAX3 and EGR1 | SOX2, JUN, and PAX3 maintain the immature state, suppress myelination programs, and regulate structural organization of Remak bundles, while EGR1 contributes to plasticity and repair-related gene expression. |

| Repair Schwann cells | JUN, MKI67, NGFR (or p75NTR), GAP43 | JUN is the master transcription factor that initiates the Schwann cell regenerative program, which involves proliferation (marked by MKI67), environmental sensing and axonal communication (via NGFR/p75NTR), and cytoskeletal plasticity (supported by GAP43) to clear debris and guide axon regrowth. |

Figure 1: Schwann cell lineage progression and differentiation during development and after peripheral nerve injury. Key transcription factors expressed during the distinct Schwann cell development stages are annotated. During early embryonic development, migratory NCCs are committed to glial lineage and generate Schwann cell precursors (SCPs), which associate with axons. SCPs give rise to immature Schwann cells (iSCs), which in turn generate pro-myelinating Schwann cells close to birth. In postnatal development, pro-myelinating Schwann cells differentiate into mature myelinating or non-myelinating Schwann cells. Upon peripheral nerve injury, axons start to degenerate, resulting in axonal and myelin debris distal to the injury site. Schwann cells post-injury reprogram into repair Schwann cells to activate a regeneration program to remyelinate the regenerated axon. Reproduced under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 from Balakrishnan, A. et al.1

Schwann cells originate from NCCs, a transient multipotent embryonic cell, which we have described in the Neural Stem Cells marker page. NCCs emerge at the intersection between the neural and non-neural ectoderm and then undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition before embarking on distinct migratory paths, which essentially dictate their final cell fates. The SOX9+/10+ trunk NCC population migrates ventrally through specific pathways and gives rise to two positionally and temporally distinct progenitor populations, namely (1) boundary cap cells and (2) Schwann cell precursors (SCPs). These ultimately give rise to Schwann cells that populate the nerve roots and peripheral nerves, respectively (Figure 2 & 3).1,2

ERG2+ (or KROZ20+) boundary-cap cells are transient progenitors derived from the NCCs that migrate ventrally and colonize the CNS-PNS interface at the dorsal root entry zones (DREZ) and motor exit points (MEP) during embryonic development.3 Boundary-cap cells serve as “gatekeepers” that anatomically position where the spinal nerve axons enter and exit the cord to regulate the integrity of the entry and exit points, while serving as the progenitor pool that contributes to several PNS cell types.4 Among these cell types are a minor subset of the spinal root Schwann cells, dorsal root ganglia (DRG) satellite glial cells, DRG sensory neurons, and dermal nerve endings, terminal glial cells and skin vasculature mural cells.3–6

On the other hand, the Schwann cells that populate the peripheral nerves are derived from NCCs that first migrate along outgrowing peripheral nerves and later give rise to the TFAP2A+/PAX3+/SOX2+/EGR1+ SCP population located near the growing nerve tip to promote nerve compaction and guide axons to their targets.2,7 As development proceeds, SCPs give rise to TFAP2A+ immature Schwann cells (iSCs), a cell type that persists up until birth in mice.8 Just before birth, individual iSCs contact a single axon. Those that contact larger-diameter axons receive high levels of neuregulin 1 (NRG1), which is essential for the survival of iSCs and development into myelinating Schwann cells.9 The process by which iSCs select a single axon for myelination is called ‘‘radial sorting” and results in the conversion of iSCs to JUN+/POU3F+/YY1+ pro-myelinating Schwann cells, a transient population that ultimately becomes myelinating Schwann cells.9 In contrast, iSCs that pair with smaller diameter axon bundles, which release lower levels of NRG1, become non-myelinating (or Remak) Schwann cells.10,11

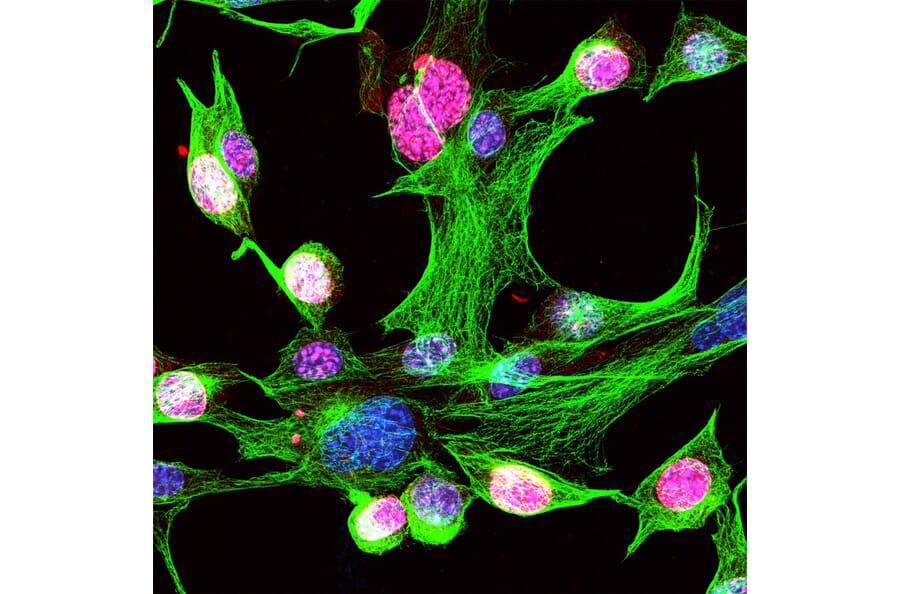

Figure 2: IHC analysis of mouse NCCs at E10.5 using anti-SOX10 antibody in green, anti-SOX9 antibody in red, and DAPI in blue. Reproduced under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 from Balakrishnan, A. et al.12

Figure 3: IHC analysis of mouse NCC at E10.5 using anti-SOX10 antibody in green, anti-EGR1 antibody in red, and DAPI in blue. Reproduced under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 from Balakrishnan, A. et al.12

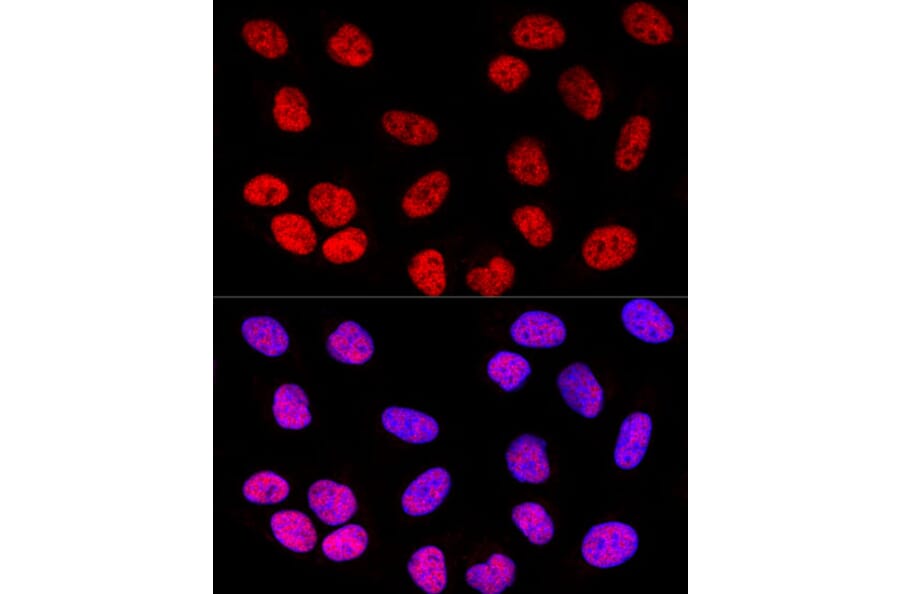

Figure 4: IHC analysis of U-2 OS cells using rabbit anti-SOX2 polyclonal antibody (A81052) in red and DAPI in blue.

Schwann cells support axons and modulate their electrical properties and are therefore indispensable for peripheral nerve functions. Myelinating and non-myelinating (Remak) Schwann cells provide two alternative modes of axon ensheathment, which are responsible for distinct action potential propagation modes: saltatory conduction versus continuous propagation, respectively13. Moreover, nerve fibers associated with myelinating versus non-myelinating Schwann cells have distinct physiological functions.13,14

Myelinating Schwann cells synthesize the multilayered myelin sheath around axons that are:14

The molecular profile of myelinating Schwann cells is characterized by the myelin structural proteins myelin protein zero (MPZ/P0), myelin basic protein (MBP), peripheral myelin protein 22 (PMP22), and periaxin (PRX), as well as the transcription factor EGR2 (or KROX20), which is the master regulator to drive myelin genes (Figure 7).15–17

In contrast, non-myelinating (Remak) Schwann cells ensheathe small-caliber (<1 μm diameter) fibers, which include:

Compared to myelinating Schwann cells, non-myelinating Schwann cells express EGR1, NGFR (or p75NTR), L1CAM, and GAP43, and lack high levels of compact myelin proteins.18 They provide trophic and metabolic support and regulate axonal conduction properties (Figure 7).19

Figure 5: IHC analysis of rat brain cerebellum using chicken anti-MBP polyclonal antibody (A85321) in red, mouse anti-calbindin monoclonal antibody [4H7] (A85360), and Hoechst in blue.

Firgutre 6:IHC analysis of HeLa cells using rabbit anti-L1CAM polyclonal antibody (A16229) in red and DAPI in blue.

Figure 7: IHC analysis of Schwann cells in the sciatic nerve of a dog. Left; anti-NGFR (p75NTR) antibody in red, anti-GAP43 antibody in green, and DAPI in blue. Right; anti-NGFR (p75NTR) antibody in red, anti-EGR2 antibody in green, and DAPI in blue. Edited and reproduced under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 from Kegler, K. et al.20

Upon peripheral nerve injury, Schwann cells respond in a timely and coordinated manner by undergoing a striking phenotypic conversion that is essential for axon survival and regeneration. During demyelination or axotomy (severing of the axon) due to injury or disease, mature Schwann cells activate a distinct repair program, rather than simply de-differentiating.21 Repair Schwann cells downregulate myelin genes such as MPZ, MBP, and PMP22, while upregulating JUN, MKI67, NGFR (or p75NTR), GAP43, OLIG1, SHH, cytokines, and other neurotrophic factors (Figure 10).22–24 This conversion reprograms Schwann cells into a phenotype that promotes proliferation, myelin clearance, macrophage recruitment, and formation of longitudinal Bungner bands that guide regrowing axons.21

Schwann cell dynamics and gene expression are significantly affected in inherited demyelinating neuropathies such as Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (CMT) and Hereditary Neuropathy with Liability to Pressure Palsies (HNPP), as many of the mutated genes encode myelin proteins.25

In CMT, different genetic subtypes disrupt distinct molecules involved in Schwann cell myelination.26 In the CMT1A subtype, PMP22 duplication leads to its overexpression and mislocalization, which in turn causes dysmyelination and onion-bulb formations.27 In contrast, MPZ mutations in the CMT1B subtype result in misfolded or ER-retained protein with reduced compact myelin staining.28 Loss-of-function PRX mutations in the CMT4F subtype impair non-compact myelin stability,29 whereas mutations in EGR2 (KROX20) reduce transcription of downstream myelin proteins. EGR2 mutations not only perturb myelin protein expression but also drive Schwann cells into repeated cycles of demyelination and remyelination, during which repair-associated markers such as NGFR (or p75NTR) and JUN are upregulated.30,31

On the other hand, HNPP is caused by a heterozygous deletion of PMP22.32 Reduced PMP22 expression by Schwann cells makes the peripheral myelin become fragile and prone to focal demyelination at compression sites.33,34 In this case, immunostaining typically shows decreased PMP22 with relative preservation of other myelin proteins, but areas of pathology display elevated NGFR (or p75NTR).35

Figure 8: IHC analysis of mouse NIH-3T3 cells using rabbit anti-MKI67 polyclonal antibody (A104333) in red, anti-beta Tubulin antibody [1B12], and Hoechst in blue.

Figure 10: IHC analysis of sciatic nerve from P7 mice using anti-OLIG1 in green, anti-MBP in cyan, and anti-NF in red. Reproduced under Creative Commons CC-BY 3.0 from Schmid, D., Zeis, T. & Schaeren-Wiemers.24