Heather van Epps, PhD | 17th September 2025

Microglial cells are a dynamic population of self-renewing, CNS-resident macrophages that are essential for the development and function of the mammalian brain and play fundamental roles in neurodevelopmental, neurological, and neurodegenerative diseases. Comprising roughly 10% of the cells in the brain,1 microglial cells are incredibly heterogeneous and can reside in an array of phenotypic, functional, and morphological states depending on both intrinsic factors, such as species, genetics, and ontogeny, and extrinsic factors, including age, spatial location, and environmental signals.1-3

Considered the brain’s first line of defense, microglial cells display a range of typical macrophage functions including phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and release of cytokines, neurotrophic factors, and other soluble mediators. They express a panoply of surface receptors that enable them to sense changes in the surrounding environment, including inflammation, neuronal damage, and the presence of pathogens.1 Via these receptors and release of soluble mediators, microglia engage in dialogue with other resident CNS cells, including astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes, as well as infiltrating peripheral cells such as macrophages and T cells.1,4

The heterogeneity of microglial cells and their exquisite sensitivity to their surroundings create challenges for the definitive identification and classification of these cells in situ. In addition, because of this acute reactivity, techniques used to study microglial cells—including in vivo imaging, RNA profiling, immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry and fluorescence-activated cell sorting—can themselves create phenotypic and functional artefacts.1

Microglial cells express a variety of surface and intracellular markers that facilitate their identification and isolation, although none is completely unique to these cells. Expression of many microglial markers is dynamic and reversible, changing in response to age, location, and perturbation/activation, while markers can also vary by species.5,6

The best microglia markers should identify microglia and distinguish them from other CNS cell types (including CNS-associated macrophages; CAMs) and infiltrating cells. The most commonly used microglia markers include:

The most specific microglia markers are the transmembrane protein TMEM119 and the nucleotide receptor P2RY12, which detects ATP released during injury.1,2 IBA1 , an actin-bundling protein involved in cytoskeletal reorganization and phagocytosis, is a common intracellular marker of activated microglia. Staining with anti-IBA1 antibodies is useful for visualising the microglial cell body and processes.

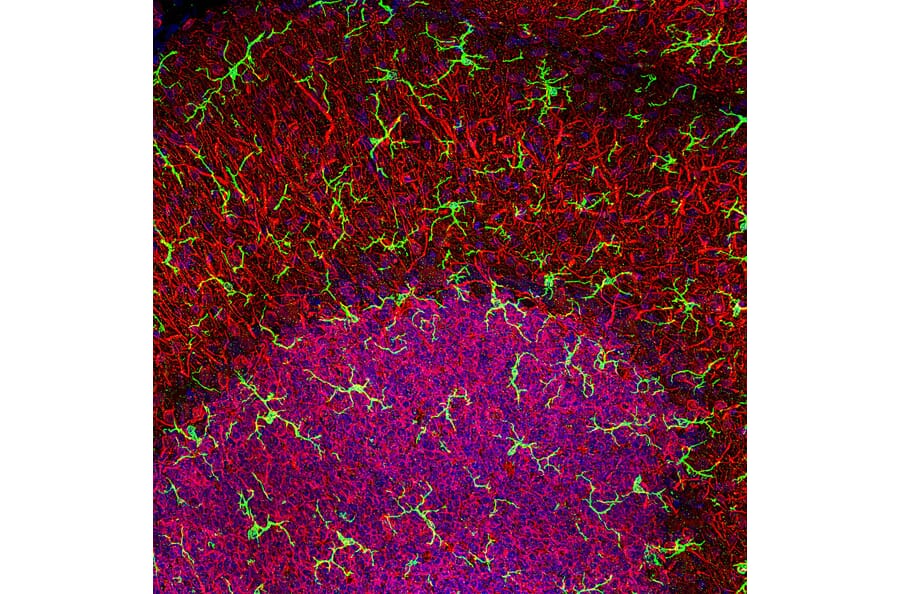

Figure 1: Confocal image of rat cerebellar. Anti-Iba1 Antibody (A104332) in green and anti-MAP2 (A85363) in red.

Figure 2: IHC of rat brain using Anti-Iba1 Antibody [ARC2301] (A307823).

Other microglial markers, including F4/80 (in mice) and CD11b, are also expressed by blood-derived macrophages in the CNS (Figure 3). Chemokine receptor CX3CR1 is another common (but non-specific) microglial marker that is fundamental in the communication between microglial cells and neurons expressing CX3CL1 (fractalkine). Both CX3CR1 and IBA1 have been used to tag microglia in vivo using CX3CR1-GFP and IBA-GFP reporter mice,7 although both molecules are also expressed by bone marrow-derived macrophages in the CNS.

Figure 3: Distinct ontogeny and markers of microglial cells and peripheral macrophage (common markers shown in green box). Reproduced and edited under CC BY 4.0 from Jurga, 2020. Front Cell Neurosci 14, 198 (2020).

Cell Surface Markers of Microglia

Cell surface markers are proteins enriched in microglia that tend to be important in sensation, cell-cell communication or migratory functions. They are particularly useful for isolating microglia by flow cytometry. Common cell surface microglia markers are described in Table 1.

| Microglia Marker | Functions |

|---|---|

| CD11b | Adhesion processes, uptake of complement-coated molecules |

| CD14 | Co-receptor with TLR4 for LPS and other pathogenic molecules |

| CD16 | Fc receptor detecting IgG, phagocytosis and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) |

| CD40 | Costimulatory receptor; indicates activation and antigen-presenting function |

| CD45 | Transmembrane protein tyrosine phosphatase that tunes immune complex signaling; distinguishes microglia from infiltrating leukocytes |

| CD68 | Lysosomal glycoprotein; phagocytic activity marker; strongly upregulated during inflammation. |

| CD80 | Together with CD86, CD28, and ICAM1, generates the co-stimulatory signals after MHCII activation; marks pro-inflammatory microglial activation |

| CD115 | Receptor for CSF1 and IL-34; required for microglial survival and proliferation |

| CX3CR1 | Fractalkine receptor; mediates neuron–microglia chemotaxis and surveillance |

| TMEM119 | Implicated in maintaining microglial identity, homeostatic transcriptional networks; exact function unknown |

| F4/80 | Cell surface glycoprotein influencing tissue residency; expressed in mice, not confirmed in humans |

| FCER1G | Fc receptor gamma chain; transduces phagocytic, ADCC and pro-inflammatory signaling in microglia |

| FCRLS | Fc receptor-like scavenger protein involved in microglial maintenance; exact function unknown |

| Sirpα | Inhibitory receptor; interacts with the broadly expressed CD47; “do not eat me” signal |

| Siglec | Family of proteins that (mostly) inhibit pro-inflammatory immune responses and phagocytosis |

| Glut5 | Microglia-enriched fructose transporter |

| P2Y12 | ADP receptor; marks homeostatic surveillant microglia |

Table 1: Membrane markers of microglial cells and their function. Information adapted from Jurga et al, 2020 1.

Figure 4: THP-1 cell line surface stained with Anti-SIRP alpha Antibody [DM8] - BSA and Azide free (A318677).

Figure 5: Immunofluorescence of THP-1 using Anti-CD11b Antibody (A13522). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue).

Intracellular Markers of Microglia

Intracellular microglial markers are commonly applied with IHC and ICC/IF; markers in the cytoplasm are particularly useful for assessments of morphology, while markers within the nucleus are useful for cell counting. Examples include IBA1, described above, as well as the transcription factors PU.1, which is essential for microglial cell development and identity, and SALL1, which is a master regulator of microglial homeostasis. Other intracellular markers are listed in Table 2.

| Microglia Marker | Function |

|---|---|

| PU.1 | Lineage-determining transcription factor essential for microglial development; regulates microglia-specific enhancer accessibility |

| IBA1 | Reorganization of microglial cytoskeleton; upregulated during microglial activation |

| HEXB | Responsible for the degradation of GM2 gangliosides and other molecules containing terminal N-acetyl hexosamines |

| Vimentin | Intermediate filament; maintains cell integrity; upregulated in microglia activation |

| Ferritin | Responsible for iron storage and its homeostasis, which is typically downregulated in inflammation |

| Sall1 | Transcriptional repressor; maintenance of microglia homeostasis, suppresses pro-inflammatory gene expression |

Table 2: Intracellular proteins and their function in microglial cells. Information adapted from Jurga et al, 2020 1.

Figure 6: IHC of human Hodgkin's lymphoma with Anti-PU.1 Antibody [PU1/2146] (A250023).

Figure 7: Immunofluorescence of mixed neuron/glial cultures stained with Anti-Vimentin Antibody (A85421) in green and Anti-GFAP (A85419) in red. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue).

Microglial cells in mice arise from yolk sac-derived primitive macrophages that begin to populate the brain rudiment around embryonic day E8-9, at which stage they are highly motile, amoeboid cells that express CD45 and high levels of CX3CR1 and F4/80. In humans, yolk sac-derived microglial progenitors appear around gestational week 2.5, which give rise to microglial cells expressing CXCR3, P2RY12, and SALL1 by gestational week 9.3,6,8–10

The arrival of microglial progenitors in the developing brain precedes the establishment of the blood-brain barrier and the onset of neurogenesis.3,10–12 Fate mapping studies in mice have shown evidence for a later influx of monocytic progenitors expressing the transcription factor Hbox813 or the chemokine receptor CCR214, which take an indirect route from the yolk sac to the brain via the aorta–gonad–mesonephros (AGM) and fetal liver, arriving in the CNS around E12.5 (Figure 8).12,15

Figure 8: Model of microglial ontogeny in mice. Reproduced and edited under CC BY 4.0 from Sharma et al. Front Cell Dev Biol 9, 65274 (2021).

When microglia progenitors enter the CNS, they are highly proliferative and motile, but as the brain develops and the brain-resident microglial cell population is established, they become increasingly (but not completely) sessile. This marks the transition from amoeboid morphology to the ramified morphology characteristic of mature microglial cells.

Unlike many peripheral immune cell types, microglial cells are generally not classified into subsets by expression of single or combinations of protein markers. Microglial cells have traditionally been dichotomised into homeostatic and activated cell states, but although these terms are still used frequently, single-cell transcriptomic data suggest that microglial states are more fluid, fluctuating in response to the physiological environment, and are also largely reversible.6

Single-cell RNA-seq studies have identified a multitude of microglial transcriptional states, which have been described using various terms. As noted, these are more likely to reflect the dynamic, highly plastic nature of the cells than to represent discrete functional subpopulations.6,16 Identifying functionally discrete populations of microglial cells is also difficult in view of the rarity with which transcriptomic data is combined with studies of protein expression and function.6

The most commonly recognized microglial cell states include homeostatic, disease associated (DAM), major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class-II-expressing, interferon-responsive, and proliferating.6,16

Disease-associated Microglia (DAM) Markers

Disease-associated microglia (DAM) are a recently identified population of microglia that are activated in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, as well as other neurological insults resulting in neuronal apoptosis.17,18 Identified by single cell transcriptomics studies of mouse models and human patient samples of Alzheimer’s disease, DAM are characterized by their phagocytic and lipid-metabolising phenotypes that allow them to contribute to the clearance of pathological amyloids such as β-amyloid, near which they are typically observed.18

DAM show downregulation of homeostatic microglial genes such as TMEM119, P2RY12, P2RY13 and CX3CR1, while retaining expression of typical microglial markers such as IBA1, CST3 and HEXB. Their activation is marked by upregulation of genes linked to lysosomal, phagocytic and lipid metabolism pathways as well as several Alzheimer’s risk factors,18–20 including:

Research on DAM has primarily focused on their involvement in Alzheimer’s disease, with the Alzheimer’s risk factor TREM2, a receptor for amyloid-β, being a major mediator of the transition from homeostatic microglia to DAM. While some transcriptomic markers in DAM associated with other neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease are consistent with those in Alzheimer’s disease, the mechanism by which the transition occurs and disease-specific markers remain to be fully elucidated.21

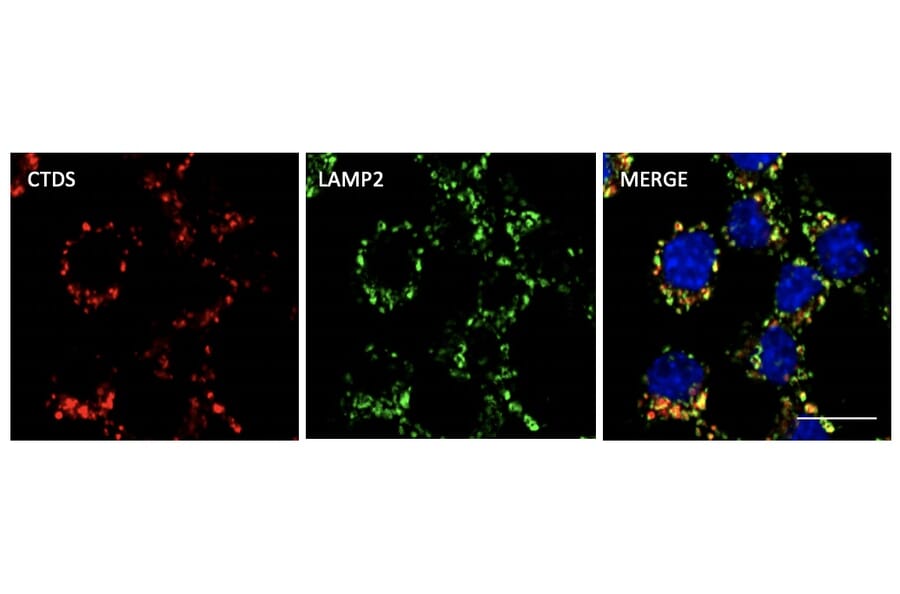

Figure 9: Immunofluorescence of RAW264.7 cells fixed with PFA and permeabilized with 0.05% Saponin, stained withAnti-Cathepsin D Antibody (A121574) at a 1:1000 dilution.

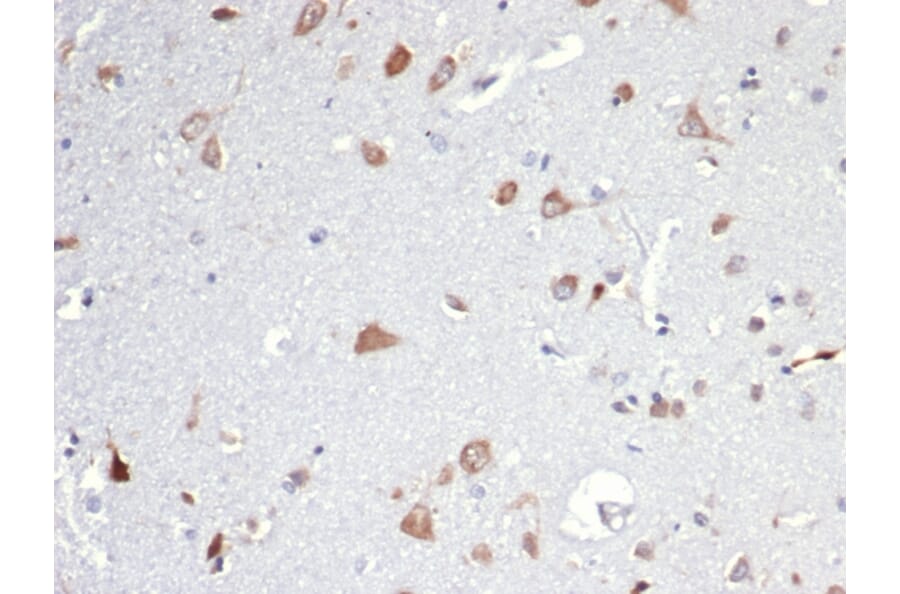

Figure 10: immunohistochemistry of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human brain using Anti-Osteopontin Antibody [OSP/4589] (A250035).

![IHC of rat brain stained with Anti-Iba1 Antibody [ARC2301]](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/307/A307823_2.jpg?profile=product_image)

![THP-1 cell line was surface stained Anti-SIRP alpha Antibody [DM8] - Azide free (A318677) at 1 µg/ml and isotype control followed by Anti-Rabbit IgG Antibody (Alexa 488).](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/318/A318677_1.png?profile=product_image)

![IHC of human Hodgkin's lymphoma using Anti-PU.1 Antibody [PU1/2146] (A250023)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/250/A250023_1.jpg?profile=product_image)