Kai Boon Tan, PhD | 14th July 2025

Neural stem cells (NSCs) are a diverse group of progenitor cell types with variable self-renewal capacities and fate plasticity to generate the three main cell types of the nervous system: neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. NSC is therefore an umbrella term that can refer to:

NSC markers are essential tools to identify and isolate NSCs. In combination with pan-neuronal markers, NSC markers can be used in research to:

During embryonic development, NSCs are generated through a series of tightly regulated developmental processes of gastrulation and neurulation. During gastrulation, the pluripotent epiblast transforms into three primary germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm.1 Under the influence of a combination of signaling pathways, such as BMP inhibition,2 FGF activation,3 and WNT modulation,4 the ectoderm is regionally specified into the neuroectoderm.

As neurulation begins, the neuroectoderm thickens to form the neural plate, which rises and folds bilaterally towards the midline, forming the neural folds. The neural folds then move toward each other and fuses to create the neural tube, the precursor to the central nervous system (CNS).5 While the anterior neural tube develops into the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain, the posterior region becomes the spinal cord as development proceeds.6

As the neural tube forms, the neural crest is generated at the dorsal aspect of the neural tube, at the interface between the neural tube and the overlying ectoderm. Neural crest cells (NCCs) later migrate and generate diverse structures such as the peripheral nervous system, melanocytes, and facial cartilage.7

Figure 1: Gastrulation and neurulation. A, The onset of gastrulation is marked by the formation of the primitive streak, which is a long groove that forms along the rostro-caudal axis of the developing embryo. During gastrulation, epiblast cells undergo a sequential migration event through the primitive streak and eventually give rise to the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. B, Part of the ectoderm is further specified into neuroectoderm via a developmental process called neurulation. b1, At the beginning of neurulation, the dorsal neuroectoderm cells begin to proliferate and form the neural plate. b2, The neural plate invaginates ventrally to form the neural groove. b3, the invagination further proceeds to deepen the neural groove, until the bilateral dorsal edges of the grove close, thereby forming the neural tube. b4, Following neural tube closure, the neural crest is generated and sandwiched between the dorsal ectoderm and the neural tube. b5, Formation of the neural tube is accompanied by a lumen filled with neural tube fluid, a specialized embryonic fluid secreted by the neuroepithelium. Figure 1A edited and reproduced under Creative Commons 4.0 CC-BY from OpenStax College, Anatomy and Physiology. OpenStax CNX. Figure 1B edited and reproduced under Creative Commons 4.0 CC-BY from Komar-Fletcher M, Wojas J, Rutkowska M, Raczyńska G, Nowacka A, Jurek JM. Negative environmental influences on the developing brain mediated by epigenetic modifications. Explor Neurosci. 2023;2:193–211.

NCCs are a transient, multipotent cell population unique to vertebrate embryos8. The neural crest is often referred to as the fourth germ layer due to NCCs’ remarkable developmental potential and contributions to the diverse cell types during development.7

Following neurulation, NCCs residing above the dorsal neural tube undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). EMT is a critical delamination step driven by a set of transcription factors such as SNAIL1/2 (or SLUG), SOX10, TWIST, and FOXD3, which downregulate adhesion molecules such as N-cadherin and occludin and activate cytoskeletal regulators.9,10 Upon EMT, NCCs migrate extensively along defined pathways depending on their final destinations, guided by extracellular matrix (ECM) cues such as fibronectin and laminin, EPHRIN/EPH repulsive signals, and chemotactic factors.11,12

Figure 2: SOX10 expression in neural crest cells. IHC analysis of dorsal root ganglia of embryonic day (E) 11.5 Sox10-Venus mice using anti-SOX10 antibody (magenta) for endogenous SOX10 protein, anti-GFP (green) for VENUS fluorescent reporter protein, and Hoechst to mark nuclei (blue). Edited and reproduced under Creative Commons 2.0 CC-BY from Shibata, S., Yasuda, A., Renault-Mihara, F. et al. Sox10-Venus mice: a new tool for real-time labeling of neural crest lineage cells and oligodendrocytes. Mol Brain 3, 31 (2010).

NCC differentiation is governed by the interplay between intrinsic transcriptional regulation and extrinsic signals, including BMP,13 WNT,14 and EDN3,15 in the environment, giving rise to over 30 major cell types. This includes neurons and glia of the peripheral and enteric nervous systems,16,17 melanocytes,18 craniofacial cartilage and bone,19 smooth muscle,20,21 adrenal chromaffin cells,22 connective tissues including adipocytes23,24 and corneal stroma cells,25 and so on.

| Molecular Markers | Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Paired box 3 and 7 | PAX3/7 | Pax3 and Pax7 are found in migrating NCCs with species-specific differences: cranial NCCs in mouse, cranial and trunk NCCs in chick and zebrafish embryos. |

| Snail family transcriptional repressor 2 | SNAI2 (or SLUG or SNAIL2) | Repress epithelial markers and facilitates the detachment of neural crest cells from the neural tube, EMT and migration. |

| Sex-determining region Y (SRY) box 10 | SOX10 | A master regulator that ensures NCCs’ multipotency, survival, mobility, and differentiation into multiple derivatives, particularly glia and melanocytes. |

| Forkhead box D3 | FoxD3 | A key fate determinant that maintains NCCs’ stemness, guides lineage choices, and prevents premature melanocyte differentiation. |

| P75 neurotrophin receptor (nerve growth factor receptor) | p75 (or NGFR) | A cell surface marker to identify early migratory NCCs, especially during their delamination from the neural tube. |

| Human natural killer-1 (cluster of differentiation 57) | HNK-1 (or CD57) | HNK-1 regulates NCC migration pathways by mediating critical cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions. HNK-1 is widely used as a cell‐surface marker to visualize and isolate NCCs. |

Table 1: Summary of common molecular markers used to characterize early and migratory neural crest cells

Figure 3: PAX7 expression in neural crest cells. IHC analysis of chick embryo neural fold at Hamburger and Hamilton stage (HH) 8 and 9 using anti-PAX7 antibody (yellow) for the neural crest and anti-SOX2 (cyan) for the neural tube. Edited and reproduced under Creative Commons 4.0 CC-BY from Roellig D, Tan-Cabugao J, Esaian S, Bronner ME. Dynamic transcriptional signature and cell fate analysis reveals plasticity of individual neural plate border cells. eLife (2017).

Neuroepithelial cells (NECs) are the NSCs that first emerge in the early neural tube and form a pseudostratified epithelium lining along the ventricular zone (VZ). Driven by WNT,26,27 FGF,28 and IGF229 signaling pathways and cell cycle regulators such as NFIB30 and CCNB1/2,31 NECs divide symmetrically, causing them to proliferate and expand the founding progenitor pool.

As development progresses, NECs transition into radial glial cells (RGCs), which serve as the major NSCs of the CNS with the multipotency to become either neurons or glia.32 RGCs exhibit a remarkable diversity of proliferative and differentiative behaviors during CNS development. An RGC can divide symmetrically to self-renew and produce two identical daughter RGCs, thereby further expanding the progenitor pool.33 Alternatively, as an RGC commits to the neural lineage, it can:

The balance between RGC proliferation and differentiation is regulated by extrinsic cues such as NOTCH, SHH,36 BMP37,38 and EGF39,40 signaling molecules, and intrinsic programs governed by a set of transcription factors such as PAX6,41,42 SOX2,43,44 and HES1/5.45,46

Figure 4: Schematic diagram showing cortical lineage progression (from left to right) during embryonic development. NSCs proliferate and differentiate into various progenitor classes with heightened fate commitment and eventually to neurons that migrate radially (bottom to top) toward the lower and upper layers of the developing gyrencephalic cortex. Upon neural tube closure, NECs populate the neural tube and self-renew to expand the founding progenitor pool. As development proceeds, NECs start to generate RGCs, which can self-renew in the ventricular zone (VZ) or generate IPs, oRGCs, or neurons directly, marking the onset of early neurogenesis. In the SVZ, IPs and oRGCs are transit-amplifying progenitors that serve as intermediate NSCs that can rapidly proliferate to further amplify the progenitor pool to substantially increase neuronal output. After peak neurogenesis, multipotent cortical RGCs and oRGCs will start to produce astrocytes and oligodendrocytes later in development. Just before birth in mice, RGCs in the dorsal lateral ganglionic eminence and VSVZ of the lateral ventricle generate postnatal or adult NSCs or neuroblasts that sustain neurogenesis in the mature brain. CP: cortical plate; IP: intermediate progenitor; IZ: intermediate zone; MZ: marginal zone; NE: neuroepithelium; NEC: neuroepithelial cell; iSVZ: inner subventricular zone; oSVZ: outer subventricular zone; oRGC: outer radial glial cell; RGC: radial glial cell; SP: subplate; VZ: ventricular zone. Edited and reproduced under Creative Commons 4.0 CC-BY from Reichard & Zimmer-Bensch. The Epigenome in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Frontiers in Neuroscience 15 (2021).

| Molecular Markers | Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Neural cadherin | NCAD (or CHD2) | Encoded by the CHD2 gene, NCAD is a calcium‑dependent cell–cell adhesion molecule that sustains the cytoarchitecture of NECs and NSCs. |

| Paired box 6 | PAX6 | PAX6 regulates NEC and RGC proliferation and drives other proneuronal genes like NEUROG2 to ensure glutamatergic fate specification. |

| Sex-determining region Y (SRY) box 2 | SOX2 | SOX2 maintains the self-renewal and multipotency of neural stem and radial glial cells by repressing premature differentiation and promoting progenitor identity. |

| Nestin (or neuroepithelial stem cell protein) | Nestin | An intermediate filament protein that supports cytoskeletal remodeling during cell division and migration. It serves as a hallmark of multipotent, undifferentiated neural progenitors and is downregulated upon differentiation. |

| Glutamate Aspartate Transporter | GLAST (or EAAT1 or SLC1A3) | A membrane-bound glutamate transporter that marks the transition of NECs into RGCs, contributing to both metabolic support and progenitor identity during neurogenesis. |

| Vimentin | VIM | An intermediate filament protein prominently expressed in NECs and RGCs to maintain cell shape and facilitates dynamic cytoskeletal remodeling necessary for cell division. |

| Hairy and Enhancer of Split 1 and 5 | HES1/5 | HES1 and HES5 are Notch-responsive transcriptional repressors for proneural genes. They promote self-renewal of neural progenitors and prevent premature neurogenesis. |

| Prominin‑1 | CD133 | A pentaspan transmembrane glycoprotein enriched in both embryonic and adult NSCs. A common marker used to isolate NSCs. |

Table 2: Summary of common molecular markers used to characterize NECs and RGCs

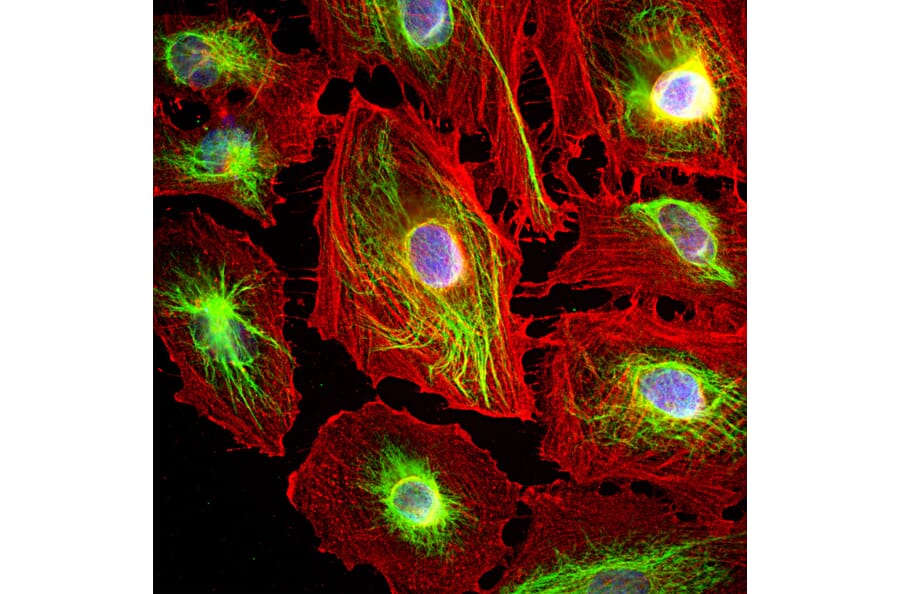

Figure 5: IHC of rat embryonic (E18) brain tissue stained with Anti-Nestin Antibody (A104326) in red. Nuclei are marked by Hoechst in blue.

Figure 6: ICC/IF of HeLa cells stained with Anti-Vimentin Antibody (A85420) in green and Anti-Actin Antibody (A85388) in red. Nuclei are marked by DAPI in blue.

Transit-amplifying progenitors are a class of rapidly dividing progenitors that arise from RGCs with limited proliferative capacity and serve as an intermediate stage between RGCs and neuronal differentiation. In the developing nervous system, transit-amplifying progenitors include IPs and oRGCs.

Differentiated from RGCs, IPs are transit-amplifying neurogenic progenitors residing and rapidly dividing in the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the developing CNS.34,47,48 As IPs progress toward neuronal differentiation, they express proneuronal genes, including TBR2 (EOMES),49 NEUROG2,50,51 and ASCL1,52,53 which are essential for neuronal fate commitment. An IP can:

This proliferative capacity enables IPCs to expand neuronal output during brain development.

While IPs are present in the nervous system of mammals, birds, and reptiles, oRGCs are specific to gyrencephalic species such as humans, non-human primates, and ferrets, which are characterized by gyrified or folded brains.54,55 oRGCs are found in the outer subventricular zone of the developing cortex and characterized by the expression of marker genes such as HOPX, TNC, FAM107A, LIFR and PTPRZ1.56,57 Similar to RGCs, oRGCs also exhibit diverse division modes and are deemed as an evolutionary intervention to substantially increase the neuron production in gyrencephalic species. An oRGC can:

| Molecular Markers | Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T-box brain protein 2 (Eomesodermin) | TBR2 (or EOMES) | A major intrinsic determinant of IP identity. TBR2 also coordinates with other factors like NEUROG2 to control neuronal differentiation and migration, and represses stemness genes like SOX2 to promote lineage progression. |

| Neurogenin 2 | NEUROG2 | A neural-specific basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor that acts as a classical proneural gene, promoting cell cycle exit and neuronal differentiation. |

| Achaete-scute family bHLH transcription factor 1 (Mammalian Achaete Scute Homolog-1) | ASCL1 (or MASH1) | ASCL1 promotes both cell cycle progression and neuronal differentiation, coordinating the expansion of progenitors and their subsequent exit from the cell cycle. |

| Homeodomain Only Protein X | HOPX | A key marker and regulator of outer radial glial cells (oRGCs) in the developing cortex and of quiescent neural stem cells (NSCs) in the adult dentate gyrus. |

| Tenascin C | TNC | A large ECM glycoprotein secreted by oRGCs contributing to the assembly of ECM for neuronal migration and cortical expansion. |

| Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Receptor Type Zeta 1 | PTPRZ1 | PTPRZ1 is enriched in oRGCs, where it regulates cell adhesion, migration, and proliferation by interacting with ECM proteins like TNC, growth factors, and cell adhesion molecules. |

Table 3: Summary of common molecular markers used to characterize IPs and oRGCs.

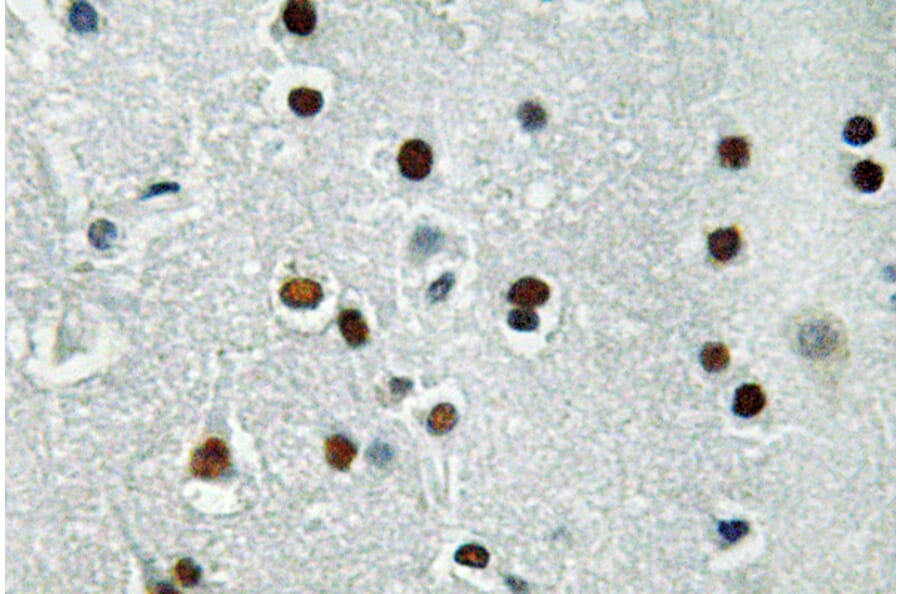

Figure 7: IHC of human brain tissue stained with Anti-ASCL1 Antibody (A95934).

Figure 8: ICC/IF of U-87MG cells stained with Anti-Tenascin C Antibody (A308041).

Neuroblasts are mitotically active, migratory neural progenitor cells that are fate-restricted to the neuronal lineage. Neuroblasts can divide during migration, with a limited proliferative capacity of up to only a few rounds of symmetric division before they exit the cell cycle and terminally differentiate into early immature neurons.59,60 Hence, they serve as an immediate progenitor source to expand the nascent neuronal pool during embryonic or fetal development and, in certain regions such as the ventricular-SVZ (VSVZ) lining the lateral ventricle61–63 and the subgranular zone (SGZ) of hippocampal dentate gyrus, throughout adult life.64

In the VSVZ, neural stem cells generate neuroblasts, which then migrate along the rostral migratory stream (RMS) toward the olfactory bulb, where they differentiate into interneurons.61–63 In the SGZ, neuroblasts arise from RGC-like progenitor cells and migrate a very short distance into the granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus, where they mature into granule neurons and integrate into hippocampal circuits.64–66

| Molecular Markers | Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Doublecortin | DCX | A microtubule-associated protein expressed almost exclusively in neuronal precursor cells, neuroblasts, and immature neurons during embryonic and adult neurogenesis. |

| Beta-III Tubulin (Class III beta-tubulin) | TUBB3 (βIII-tubulin or TUJ1) | A neuron-specific microtubule protein expressed from the earliest stages of neuronal differentiation. It is widely used as a marker for immature and mature neurons, distinguishing them from NSCs. |

| Polysialylated Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule | PSA-NCAM | Highly expressed on the surface of neuroblasts and immature neurons. PSA-NCAM reduces cell-cell adhesion, enabling cell migration, neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis during brain development. |

| Paired Like Homeobox Protein 2B | PHOX2B | PHOX2B drives cell cycle exit and promotes the transition of neuroblast to post-mitotic neurons. |

Table 4: Summary of common molecular markers used to characterize neuroblast and immature neurons

Figure 9: ICC/IF of of E20 rat cortical neuron-glial primary culture stained with mouse anti-DCX monoclonal antibody [3E1] (A85376) in red, Anti-MAP2 Antibody (A85363) in green, and DAPI in blue.

Figure 10: ICC/IF of P19 mouse embryonic carcinoma cells driven toward neuronal differentiation in vitro stained with mouse anti-TUBB3 monoclonal antibody [TU-20] (A86691)in red and DAPI in blue.

![ICC/IF - Anti-Doublecortin Antibody [3E1] (A85376)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/85/A85376_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![ICC/IF - Anti-beta III Tubulin Antibody [TU-20] (A86691)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/86/A86691_817.jpg?profile=product_image)