Kai Boon Tan, PhD | 22nd August 2025

Oligodendrocytes are a specialized type of glial cell in the central nervous system (CNS) that produces myelin, a fatty insulating substance that wraps around neuronal axons. This myelin sheath serves to speed up the transmission of electrical impulses along nerve fibers, thereby enabling rapid and efficient communication between neurons.

Oligodendrocyte generation, maturation, and functional diversity are orchestrated by a tightly regulated sequence of transcriptional programs and signaling events. Here, we describe oligodendrocyte lineage progression, maturation, functional roles in myelination and remyelination, and compile common molecular markers at each stage.

Oligodendrocyte markers are important tools in neuroscience research. Below are some examples of how oligodendrocyte markers can be used in research:

| OPC or oligodendrocyte stage | Key Marker(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Pan-oligodendroglia lineage | OLIG2, SOX10 | OLIG2 activates SOX10 expression, and their co-expression is active throughout the oligodendrocyte development, differentiation and maturation |

| OPCs | NKX2.2, PDGFRα, NG2 (CSPG4), CXCR4 | Transcription factors responsible for OPC fate commitment, proliferation, survival and migration |

| Early Differentiation | MYRF | Transcription factors to activate myelin genes |

| Pre-Myelinating Oligodendrocytes | O4, BCAS1 | Markers of newly differentiating oligodendrocytes |

| Mature Myelinating Oligodendrocytes | MBP, PLP1, CNPase, MOG, CC1 | Structural proteins localize to compact and non-compact myelin |

| Remyelinating Oligodendrocytes | GSTπ, ASPA | Marker for newly differentiated oligodendrocytes in response to injury |

| Mature Oligodendrocytes | MCT1 | Metabolic support for axons via lactate transport |

Figure 1: Immunofluorescence of rat brain cerebellum stained with Anti-Myelin Basic Protein Antibody [7D2] (A85329) (red) and Anti-NF-M Antibody (A85323) (green). Nuclei are marked by DAPI in blue.

Figure 2: IHC of mouse brain stained with Anti-Myelin PLP Antibody (A306001) in red. Nuclei were stained by DAPI in blue.

Oligodendrocytes are derived from oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, which originate from radial glial cells (RGCs), the primary neural stem cells (NSCs) of the embryonic central nervous system (CNS). As described in the NSC markers page, RGCs line the ventricular zone of the neural tube and generate all major CNS cell types, including neurons, astrocytes, ependymal cells, and oligodendrocytes.

In the forebrain, oligodendrocytes are generated in three waves from the spatiotemporally distinct cohorts of NSCs (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Schematic representation of the origins of distinct waves of forebrain and spinal cord oligodendrocytes. At E12.5 in mice, the first wave of forebrain and spinal cord oligodendrocyte precursors (OPCs) is generated from the ventral telencephalon and ventral neural tube. At E15.5, forebrain OPCs arise from the lateral ganglionic eminence, while spinal cord OPCs emerge from the dorsal neural tube. The final wave of forebrain and spinal cord oligodendrogenesis takes place after birth (P0), with forebrain oligodendrocytes produced from dorsal telencephalic progenitors, and spinal cord oligodendrocytes arising from progenitors from the central canal subependymal zone. Edited and reproduced under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 from van Tilborg, E. et al. 1

Figure 4: IHC analysis of postnatal mouse brain at postnatal day (P)14 using anti-OLIG1 antibody in blue, NKX2.2 in green, and V5-tagged Tensin3 in red. Edited and reproduced under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 from.10

Similar to the forebrain, spinal cord OPCs originate from the in three distinct NSCs waves in the neural tube:

Figure 5: IHC analysis of mouse adult spinal cord using anti-GFP antibody in green to report ASCL1, (left panel) anti-PDGFRα antibody in red, anti-OLIG2 in blue, and (right panel) anti-NG2 antibody in red. Edited and reproduced under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 from Kelenis, D. P. et al.18

As CNS development progresses into late embryonic and early postnatal development, OPCs exit the cell cycle and begin to differentiate into oligodendrocytes. During this process, OPCs maintain OLIG2 expression, which in turn activates SOX10.

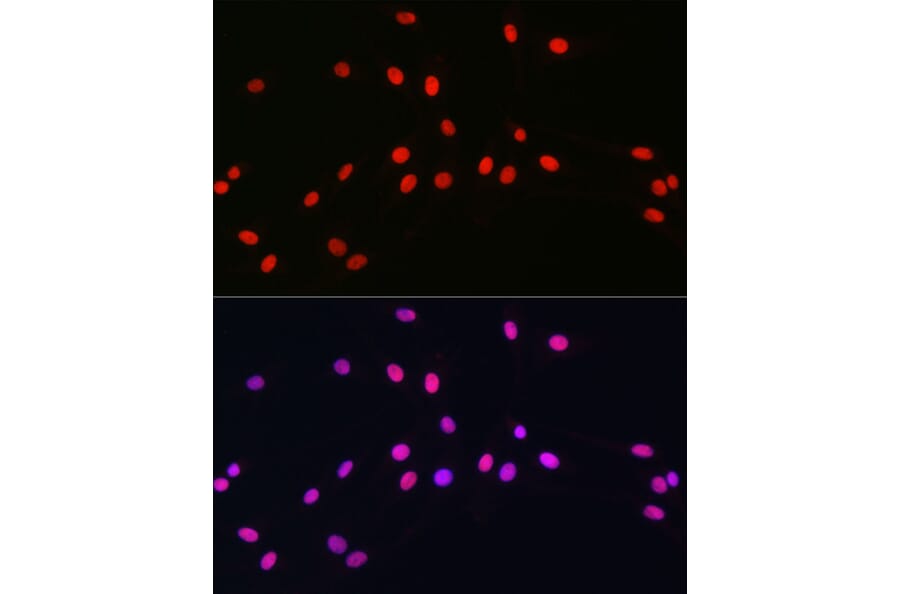

Figure 6: IHC analysis of C6 cells using rabbit Anti-SOX10 polyclonal antibody (A90639) in red and DAPI in blue.

Figure 7: IHC analysis human cerebellum stained with Anti-OLIG2 Antibody [OLIG2/2400] (A248077) in red and DAPI in blue.

Subsequently, SOX10 directly cooperates with Myelin Regulatory Factor (MYRF) to suppress progenitor genes such as PDGFRA and NG2, while activating expression of myelin proteins, including Myelin Basic Protein (MBP), Proteolipid Protein 1 (PLP1), and Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein (MOG) to prepare for myelination.19–21 Early during this transition, newly differentiated oligodendrocytes start to express the sulfatide epitope O4, on the cell surface and the cytoplasmic protein BCAS1, both of which are essential in the oligodendrocyte terminal differentiation from OPCs (Figure 8).22,23

Figure 8: IHC analysis of oligodendroglia cell culture using anti-BCAS1 antibody in magenta, anti-MBP antibody in red, anti-Thioflavin S antibody in green, and DAPI in blue. Edited and reproduced under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 from Kaji, S. et al.24

Peak myelination takes place in the early postnatal weeks in rodents25,26 but extends through adolescence, with remodeling myelination persisting into adulthood in humans.27,28 During peak myelination, oligodendrocytes actively ensheathe axons in white matter tracts such as the corpus callosum and optic nerve. Interestingly, this process aligns with critical developmental behavioral milestones, including motor coordination and sensory processing.29 In humans, myelination begins prenatally at gestational week 20, peaks postnatally, and extends up to the age of 25.30 It has been postulated that the protracted timeline allows activity-dependent refinement, where neural circuit usage fine-tunes myelin thickness and internode length to optimize conduction velocity.27,30 Remarkably, remodeling myelination persists into adulthood to support lifelong learning and memory consolidation through oligodendrocyte turnover and local myelin adjustments.29,31

Under the control of MYFR, mature oligodendrocytes synthesize specialized myelin proteins that structurally stabilize the multilamellar myelin sheath.32 Among these:

Figure 9: IHC analysis of remyelination in the brain of the mouse experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model using anti-MOG antibody in blue, anti-NF antibody in red, and anti-GFP antibody in green to show membrane-associated GFP (mGFP) in cells of the NG2+ oligodendroglia lineage. Edited and reproduced under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 from Mei, F. et al.37

Figure 10: Immunofluorescence of oligodendrocytes in a cortical neuron-glial cell culture from E20 rat stained with Anti-Myelin Basic Protein Antibody (A85321) in red. Nuclei are marked by DAPI in blue.

Figure 11: Immunofluorescence of rat cerebellum section stained with Anti-CNPase Antibody [1H10] (A85413) in green and Anti-NF-M Antibody (A85324) in red.

Activity‑dependent myelination by oligodendrocytes is mediated via neuregulin signaling through ErbB family receptors on oligodendrocytes to fine‑tune conduction velocity and circuit synchrony.38–40 Apart from myelination, oligodendrocytes also play active roles in neuronal support and plasticity. For instance, oligodendrocytes express Monocarboxylate Transporter 1 (MCT1) to shuttle lactate and other metabolites to axons, ensuring energy supply during high‑frequency firing (Figure 12).41,42

Figure 12: IHC analysis of oligodendrocyte culture using anti-MCT1 antibody in green and anti-MBP antibody in red. Edited and reproduced under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 from Lai, Q. et al.43

A persistent PDGFRA+/NG2+ OPC population is distributed throughout the adult CNS. This OPC pool remains in a quiescent state under normal physiological conditions and is dynamically poised to respond to CNS injury.44,45 Upon injury, these OPCs rapidly upregulate PDGFRα and chemokine receptors such as CXCR4 to enter the cell cycle to proliferate and migrate towards sites of damage, where they later differentiate into oligodendrocytes to facilitate remyelination.45–47

As OPCs mature into remyelinating oligodendrocytes, some proteins are markedly upregulated. Among these, glutathione S-transferase π (GSTπ, GST3 or GSTP1) and aspartoacylase (ASPA) are commonly used as molecular markers of newly formed oligodendrocytes and remyelination.48–50 Since GSTπ plays crucial roles in cellular detoxification and protection against oxidative stress, it serves as a reliable indicator of new oligodendrocyte generation in demyelinated lesions.49,51 ASPA, which is an enzyme involved in N-acetylaspartate metabolism, is also robustly expressed in oligodendrocytes and plays a physiological role in myelin lipid synthesis and maintenance.52,53 Orchestrating with expression of myelin proteins, including PLP1, MBP, MOG, and CPNase, the enrichment of GSTπ and ASPA in these newly generated oligodendrocytes is a hallmark of their engagement in restoring functional myelin sheaths around axons during CNS repair.

![Immunofluorescence of rat cerebellum section stained with Anti-CNPase Antibody [1H10] (A85413) in green and Anti-NF-M Antibody (A85324) in red.](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/306/A306001_5.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Anti-OLIG2 Antibody [OLIG2/2400] (A248077)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/248/A248077_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Immunofluorescence of rat cerebellum section stained with Anti-CNPase Antibody [1H10] (A85413) in green and Anti-NF-M Antibody (A85324) in red.](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/85/A85413_1.jpg?profile=product_image)