Ryan Hamnett, PhD | 31st January 2025

Accurate measurements of cell health, intercellular signaling, gene expression and cellular metabolism are essential to determine the effects of genetic manipulations and drug treatments on a population of cells, from foundational research through to drug discovery and pharmaceutical development.

Cell-based assays using live or fixed cells capture a complete picture of cell behavior, including multifaceted interactions that are otherwise lost in biochemical assays. By providing direct readouts of cellular function, cell-based assays can better reflect complex biological pathways.

Cell-based assays are a collection of techniques used to measure and characterize the activity and biological state of cells. In contrast to biochemical assays, which often analyze recombinant proteins or cell lysates, cell-based assays assess living or fixed cells to better determine their physiological functioning. Because cells are a complete functional unit containing a multitude of active processes and pathways, readouts from cell-based assays reflect physiological complexity better than more reductive approaches do.

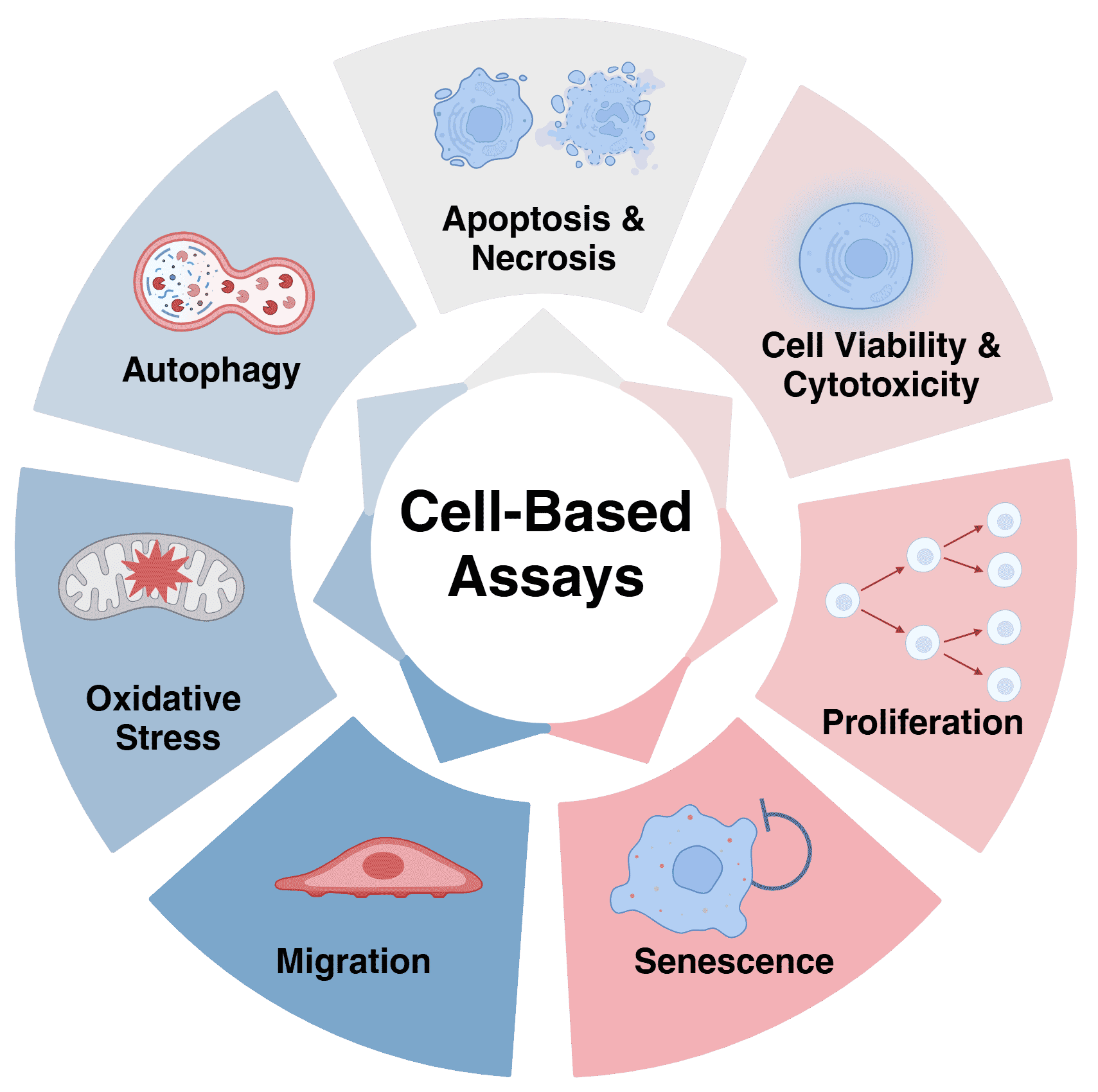

Figure 1: Examples of cell-based assays

Aspects of cell biology that can be assessed by cell-based assays include apoptosis, proliferation, cell health and viability, senescence, cell cycle state, and metabolic function.

Cell-based assay outputs can come in form of absorbance, fluorescence, and luminescence, while some are label-free. They can often be used with both 2D and 3D culture methods.

The greatest advantage of cell-based assays is that they allow measurements of complex physiological processes of the cell in a more holistic manner. This can provide researchers with more realistic models of how tissues or whole organisms will ultimately respond to a given genetic manipulation, pharmacological treatment or intervention than they would be able to model based only on biochemical responses of individual receptors or enzymes.

Cell-based assays can also be expanded in complexity to take into account other experimental factors, such as the environmental context (e.g. co-cultured cells) or genetic background, which will correspond to in vivo conditions more closely than in vitro assays could. Similarly, some cell-based assays can be monitored longitudinally over time to assess the long-term effects of a drug treatment, or its impacts when combined with other treatments or environmental influences.

Due to being based on cell culture approaches, cell-based assays are highly amenable to high-throughput screening. Many compounds can be screened in parallel to determine their impacts on processes such as apoptosis or proliferation, saving time and money.

The versatility of cell-based assays has made them popular at all stages of biological research, allowing researchers to measure the effects of a wide variety of compounds in their favorite cell type, genetic background, and environmental conditions.

Research Applications for Cell-Based Assays

Cell-based assays play an important role in foundational research by allowing researchers to investigate the role of pathways and genes in complex cellular processes during cell health and disease. For example, the downstream effects of knocking out or altering a gene on processes such as proliferation can be determined, and then pharmacological or further genetic studies can shed light on the mechanistic pathways involved.

Cellular assays can also be used for routine measurement of cell health and viability, and for determining optimal cell culture conditions.

Drug Discovery Applications for Cell-Based Assays

Cells are essential to drug development because all compounds are tested for efficacy and safety in cellular models before in vivo or clinical tests go ahead. The high-throughput nature of cell-based assays makes them ideal at numerous points through the drug discovery and development pipeline:

Apoptosis is a tightly regulated form of cell death that occurs to destroy cells that are no longer needed, are a danger to the organism, or are too damaged to continue to function. Apoptotic pathways are common targets for drugs because cell death is desirable for conditions such as cancer. Apoptotic cells exhibit characteristic changes that can be easily assayed, often by fluorescent means, such as DNA fragmentation, blebbing, and disruption of the plasma membrane. Many assays allow the distinction of apoptosis from necrosis, which is important for therapeutic outcomes as necrosis causes significantly more inflammation and damage to nearby tissues.

Annexin V Staining

Early in the apoptotic process, the phospholipid phosphatidylserine is translocated from the inner surface of the plasma membrane to the outer surface. Annexin V is a protein that binds to phosphatidylserine, meaning that the localization of phosphatidylserine can be easily determined by flow cytometry or immunofluorescence with Annexin V conjugated to a fluorescent reporter such as FITC. Necrotic cells can be distinguished from apoptotic cells with the addition of propidium iodide (PI). PI can only enter cells that have a ruptured membrane, indicative of either necrosis or late stage apoptosis.

Figure 2: Assessing apoptosis and necrosis with Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI).

Caspase Activity Assays

Caspases are enzymes that are activated during apoptosis. Apoptosis can therefore be inferred by adding a substrate that will be catalyzed by caspases to produce a detectable product. These products may be fluorescent or alter absorbance at a specific wavelength, such as p-nitroaniline.

Comet Assays

Comet assays detect DNA damage, a classic sign of apoptosis, by visualizing the migration of DNA fragments by electrophoresis. To visualize the damaged DNA, cells are imbedded into agarose and placed onto a slide. Immersing the slide in cell lysis solution lyses the plasma membrane and removes cytosolic material, leaving protein‐depleted nuclei with supercoiled DNA ( ‘nucleoids’), which is then treated with an alkaline solution to denature the DNA. An electric field is then applied, causing the DNA to migrate, which is then stained with a DNA-specific fluorescent or chromogenic stain and analyzed by microscopy. Fragmented DNA appears as a smear or comet tail, which may indicate that the cells were undergoing apoptosis.

Mitochondrial Membrane Assays

Increased mitochondrial membrane permeability is a key feature of both apoptosis and necrosis due to the release of multiple factors from the mitochondria into the cytosol that hasten the death of the cell. Measuring how permeable mitochondria are is therefore a marker of apoptosis.

One method to determine mitochondrial permeability is to study mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) opening. The MPTP is a protein on the inner mitochondrial membrane that can open in response to apoptotic effectors such as high Ca2+ and reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting in swelling and rupture of mitochondria.1 Cells can be loaded with calcein-AM, a non-fluorescent molecule that diffuses into the cytosol and mitochondria before being cleaved by endogenous esterases to calcein. Calcein is fluorescent and does not easily cross membranes. Addition of cobalt chloride quenches calcein in the cytosol but cannot reach the calcein within the mitochondria, resulting in only mitochondrial fluorescence being visible. The mitochondria will remain brightly fluorescent unless the MPTP is open (indicative of apoptosis), allowing the cobalt chloride access to the mitochondrial calcein.2

Another method is to use the cationic JC-1 dye as a fluorescent indicator of mitochondrial membrane potential. In normal conditions, oxidative phosphorylation results in an electrochemical proton gradient across the mitochondrial membrane, whereby the mitochondrial matrix is negatively charged while the intermembrane space is positively charged due to the accumulation of protons. This gradient is then used to produce ATP for the cell. In healthy cells, the cationic JC-1 accumulates in the energized and negatively charged mitochondria. In its monomeric form, JC-1 naturally produces green fluorescence, but this shifts to red when it aggregates in the mitochondria. In unhealthy or apoptotic cells, increased mitochondrial permeability results in a loss of the electrochemical gradient. JC-1 therefore fails to accumulate at the concentration at which it would begin to aggregate, so it retains its original green fluorescence.3 The ratio of red to green fluorescence indicates the health of the mitochondria.

Figure 3: Assays for assessing mitochondrial permeability

TUNEL Assays

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) dUTP Nick-End Labeling (TUNEL) assays reveal apoptotic cells in situ by highlighting DNA fragmentation, a hallmark of apoptosis. In TUNEL assays, the TdT enzyme labels the 3’-OH end of double strand breaks with a modified deoxynucleotide, dUTP.4 The modification is usually a fluorophore such as FITC, but other modified dUTPs such as BrdUTP, EdUTP or biotinylated dUTP can be used for more sensitivity or flexibility in detection. TUNEL assays can be applied to histological preparations or in flow cytometry.

Autophagy refers to the lysosomal degradation or recycling of proteins or organelles. Autophagy is one method of balancing apoptosis: the two processes can be stimulated by the same stressors, but autophagy can increase the threshold of stress required for apoptosis induction by selectively removing damaged cytosolic components.5 Conversely, caspases activated during apoptosis cleave some autophagic proteins, tilting the balance towards cell death instead of autophagy.

One way of detecting autophagy is using fluorophores that increase in fluorescence upon exposure to the low pH environment of the lysosome. Fluorophores, such as Mtphagy Dye, can be targeted to bind to specific organelles, such as the mitochondria, after which they will only exhibit strong fluorescence in the case of fusion with the lysosome.6

Cell proliferation assays indicate actively dividing cells. Proliferation is a useful indicator of cell viability, though it is distinct, as viable cells are not necessarily proliferative.

One of the most direct markers of cell proliferation are those that allow the measurement of DNA synthesis. Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) is a thymidine analog that is incorporated into DNA during replication. Antibodies against BrdU will therefore highlight actively dividing cells.

Another direct measure of proliferation is to load cells with a well-retained fluorophore that is passed on to daughter cells upon division. When cells divide, the intensity of the stain will be halved, allowing generational tracking of cells.

Cell viability refers to the proportion of cells in a population that are capable of surviving under a given set of conditions, such as the environmental setting or genetic context. Precise numbers of live and dead cells can be measured by fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry, while plate readers measure the absorbance of a colored product that correlates with the number of viable cells.

Two main methods of determining cell viability exist. The first involves complementary probes that stain live and dead cells different colors in a single sample, which can be visualized by microscopy or flow cytometry. These typically reflect commonly accepted markers of cell viability: plasma membrane integrity and esterase enzyme activity. Dyes like propidium iodide (PI) can only penetrate disrupted plasma membranes, and so mark dead or dying cells. For live cells, the non-fluorescent calcein-AM can easily penetrate intact plasma membranes to reach the cytosol, where it is cleaved to calcein by intracellular esterases in viable cells. Calcein is fluorescent and so readily marks live cells.

Dye exclusion methods, such as staining with trypan blue, are a distinct and simple approach that relies on living cells actively exporting dye from their cytoplasm, leaving only dead cells stained.

The second method assesses the activity of metabolic enzymes as a marker of viability, reflecting the function of mitochondria in viable cells. Often these enzymes are mitochondrial dehydrogenases such as NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, which reduce tetrazolium salts such as MTT, WST-1, WST-8, XTT and MTS to their colored formazan products inside the cell cytoplasm and mitochondria. The change in absorbance is proportional to the number of viable cells in a sample. The specific choice of salt is largely determined by requirements of sensitivity, toxicity to cells, convenience, cost and color. The fluorescent dye resazurin can be used in a similar way to the tetrazolium salts in related assays.

Cytotoxicity refers to the ability of a compound to cause harm to cells, resulting in a reduction in growth and division, necrosis, or apoptosis. These assays are complementary to cell proliferation and cell viability assays, and can therefore be assessed with some of the same tools such as live/dead staining to demonstrate loss of membrane integrity.

One method of measuring plasma membrane integrity is to assess lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity. LDH is a stable enzyme that is released into the cell culture medium upon plasma membrane damage, meaning more LDH activity reflects greater cytotoxicity. The LDH assay is based on the interconversion of pyruvate and lactate and concomitant interconversion of NADH and NAD+ by LDH. The production of NADH is used to reduce a tetrazolium salt, which then forms a colored compound that can be measured. The intensity of the color correlates with the number of lysed cells.

Cellular migration underlies several different processes in living organisms, including wound healing, tissue formation, immune defense and cancer progression. Cells migrate towards (or, less frequently, away from) chemical and mechanical signals, such as chemotaxis of some immune cells towards sites of inflammation. Cell migration assays can distinguish migratory from non-migratory cells within a population, as well as providing measures of the rate of migration, direction of movement and distance traveled.

Common types of cell migration assay include loading cells with a well-retained, non-toxic, fluorescent dye so that they can be tracked, wound healing (or scratch) assays, and transwell assays. In wound healing assays, a gap is introduced into a confluent monolayer by scratching the cells away, and the migration of the remaining cells into the ‘wound’ is monitored. Transwell assays allow the measurement of cell migration from one chamber to another through a porous membrane, often towards a chemoattractant.

Figure 4: Transwell migration assay

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive free radicals derived from molecular oxygen (O2), including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide (O2•-), hydroxyl radical (OH•), and singlet oxygen (1O2).

ROS are naturally produced in the cell, particularly by NADPH oxidases and the electron transport chain in the mitochondria, as a result of cellular metabolism or external signals such as growth factors and chemokines.7 ROS have a variety of physiological functions, including in cell signaling, proliferation and differentiation.7 However, ROS are toxic in large quantities because they cause damage to DNA, RNA and proteins.

Pathological ROS production can occur under conditions of oxidative stress due to intrinsic factors such as inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction, or extrinsic factors such as heavy metals, radiation and drugs.8 When uncontrolled, ROS are highly toxic to cells and typically trigger apoptosis.

Methods of detecting levels of ROS in cells often use a fluorescent probe that is not fluorescent in a reduced state, but fluoresces upon oxidation by ROS for detection by flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy. The probes can be for general ROS levels or specific to certain ROS, such as hydrogen peroxide or singlet oxygen. One example is DCFH-DA, a cell-permeable probe that is hydrolyzed into DCFH by intracellular esterases. DCFH is not fluorescent and cannot pass through the cell membrane, but it is oxidized by ROS to produce the fluorescent DCF. Stronger fluorescence reflects greater levels of ROS.

Another relevant aspect of oxidative stress that can be assayed is the antioxidant capacity. Antioxidants ‘mop up’ ROS and are important for cellular ROS homeostasis, meaning these assays test the ability of a sample to deal with ROS. This is achieved by measuring how long a fluorescent compound is able to maintain its fluorescence in the presence of a regular source of ROS. ROS damage the fluorophore, so the longer the fluorescence is sustained, the better the antioxidant capacity of the sample. Levels of glutathione, an important antioxidant, can be assayed by their reaction with DTNB (Ellman’s reagent) to produce a colored product.

Kits are also available to measure products, such as advanced oxidation protein products, and enzyme activity, including superoxide dismutase (SOD1), relating to oxidative stress.

Senescence is a process of stress-induced cell-cycle arrest and repression of cell-cycle-related gene expression in previously replication-competent cells.9 It is often referred to as biological aging; senescent cells are alive but no longer divide. While senescence may be a mechanism for preventing cancer, an accumulation of senescent cells in organisms can lead to inflammation during old age.10

Senescence is associated with several biomarkers, most notably in an increase in the activity of lysosomal enzyme senescence-associated-β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal).9 A simple colorimetric assay for SA-β-gal can be performed by IHC at pH 6 by staining cells or tissue with X-Gal (or fluorescent equivalent such as FDG), a chromogenic substrate that creates a blue product when cleaved by β-gal. SA-β-gal activity is usually not detectable in presenescent or quiescent cells.

| Assay | Product Name | Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|

| Apoptosis | Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit | A478 |

| Apoptosis | Annexin Fluorescent Dye 488 Labelled / PI Apoptosis Detection Kit | A319604 |

| Apoptosis | Caspase-3 Assay Kit (Colorimetric) | A319626 |

| Apoptosis | Comet Assay Kit (3-Well Slides) | A319634 |

| Apoptosis | Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit (JC-1) | A319761 |

| Apoptosis | One-step TUNEL Apoptosis Assay Kit (Green Fluorescence) | A319767 |

| Cell Proliferation | Cell Cycle Staining Kit | A319632 |

| Cell Viability | Cell Counting Kit | A319631 |

| Cytotoxicity | Live and Dead Cell Double Staining Kit | A319650 |

| Cytotoxicity | LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit | A319649 |

| Cell Migration | Live Cell Tracking Kit (Green Fluorescence) | A319651 |

| Cell Migration | Cell Migration Assay Kit (24 well, 8 µm) | A319633 |

| Oxidative Stress | Advanced Oxidation Protein Products Assay Kit | A319657 |

| Oxidative Stress | Hydrogen Peroxide Assay Kit | A319692 |

| Senescence | Senescence beta Galactosidase Staining Kit | A319772 |

| Senescence | SPiDER-ßGal | A57211 |

Diagrams created with BioRender.com.