Ryan Hamnett, PhD | 5th February 2025

Macrophages are a diverse group of immune cells found in almost all tissues of the body. Macrophages were originally identified as phagocytes of pathogens, acting as one of the first lines of defense by recognizing foreign material and ingesting it for degradation. Since then, research into macrophages has revealed numerous additional functions, including phagocytosing host cell debris, mediating tissue homeostasis and repair, producing growth factors for host protection and organ development,1 and recruiting other immune cells to sites of inflammation through the release of cytokines and chemokines.2 While macrophages are often considered as part of the innate immune system, they also have an important role in the adaptive immune system by activating T cells via the presentation of antigens in association with major histocompatibility class II (MHCII) proteins on their surface.

A large number of molecular markers for macrophages have been identified to classify the great phenotypic diversity that macrophages exhibit in different niches and situations. These markers allow researchers to quantify their abundance and function within different tissues at different times, with alterations in macrophage numbers known to contribute to metabolic disorders, autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammation and cancer.

Macrophages are found in almost all tissues throughout the body, where they exhibit a high degree of specialization appropriate to their specific roles within each tissue of residence, or niche. Examples of different tissue-resident macrophages include microglia in the brain, alveolar macrophages in the lungs, and Kupffer cells in the liver.

In addition to their location, macrophages can be activated by factors such as microbial presence, signaling molecules and cell debris to express pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory factors. These subtypes are referred to as classically activated M1 macrophages and alternatively activated M2 macrophages.

The appearance, function and the markers that characterize different populations of macrophages are therefore largely determined by four key factors: developmental origin, amount of time spent in niche, inflammation state, and local signaling factors.3 The multifaceted nature of macrophage development has resulted in a large number of different macrophage subcategories, with distinct markers employed to identify members of different populations.

Few unique markers are available to identify a specific subtype of macrophage, with multiple markers typically needed to categorically characterize a macrophage population. Some pan-macrophage markers that cover the majority of macrophages include:

Some established pan-macrophage markers, such as CD68, are also found on other mononuclear phagocytes and even non-myeloid cells.4

Figure 1: Flow cytometry of human peripheral whole blood stained with PE-Cy7-conjugated mouse anti-CD11b [ICRF44] (A121977).

Figure 2: IHC of FFPE of human tonsil stained with monospecific mouse anti-CD68 [LAMP4/1830] (A250763).

Macrophages were originally believed to be a relatively homogenous population that was part of the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), and that was regularly replenished by circulating monocytes migrating (extravasating) into tissues and differentiating into locally adapted macrophages.5 Though this is true for macrophages in some tissues, other tissues comprise a mixture of macrophages of different origins. Macrophages are now known to arise from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the bone marrow or fetal liver (which also give rise to monocytes), or during embryogenesis from multipotent erythro-myeloid progenitors (EMPs) in the yolk sac.

Fate-mapping technologies have revealed that macrophages of embryonic origin generally do not require replenishment from circulating monocytes, proliferating within tissues instead, and that they are particularly prevalent in the brain (microglia), lungs (alveolar macrophages), spleen, liver (Kupffer cells), and skin (Langerhans cells).5 In contrast, macrophage populations in the gut, dermis and heart are more heterogeneous, showing evidence of monocyte-derived macrophages.5 Nonetheless, macrophages show a large degree of plasticity and flexibility, able to differentiate into competent tissue-resident macrophages regardless of origin.6

High levels of F4/80 (EMR1) is a marker of macrophages derived from the yolk sac, while high CD11b defines macrophages from HSCs.7 Throughout development, yolk sac-derived macrophages from EMPs can be defined at various stages by expression of the receptor tyrosine kinase c-Kit, colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R), and CX3CR1.8 In addition to CD11b, bone-marrow derived macrophages can be marked by high Ly6C, CD14 and CD16.

Figure 3: IHC of FFPE human tonsil stained with recombinant mouse anti-c-Kit [RM359] (A121476).

Figure 4: Flow cytometry of human peripheral blood cells stained with FITC-conjugated mouse anti-CD14 [MEM-15] (A85585).

While macrophages fulfill broadly the same roles throughout different tissues, such as immune surveillance and tissue remodeling, the specific requirements of some tissues necessitate greater specialization and functionality (Table 1).9,10 For instance, microglia are known to modify synaptic connections, while adipocyte-associated macrophages can regulate insulin sensitivity. Table 1 illustrates specific features of macrophages found within different tissues.

| Tissue | Macrophage | Specific Functions | Key Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adipose tissue | Adipose tissue macrophages | Removing dead adipocyte debris, lipid uptake and storage, iron regulation | ABCA1, CD36, PLIN2, CD9, Tfrc, Hmox111 |

| Bone | Osteoclasts | Bone remodeling by resorbing bone matrix, regulating calcium homeostasis | Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), cathepsin K, RANK12 |

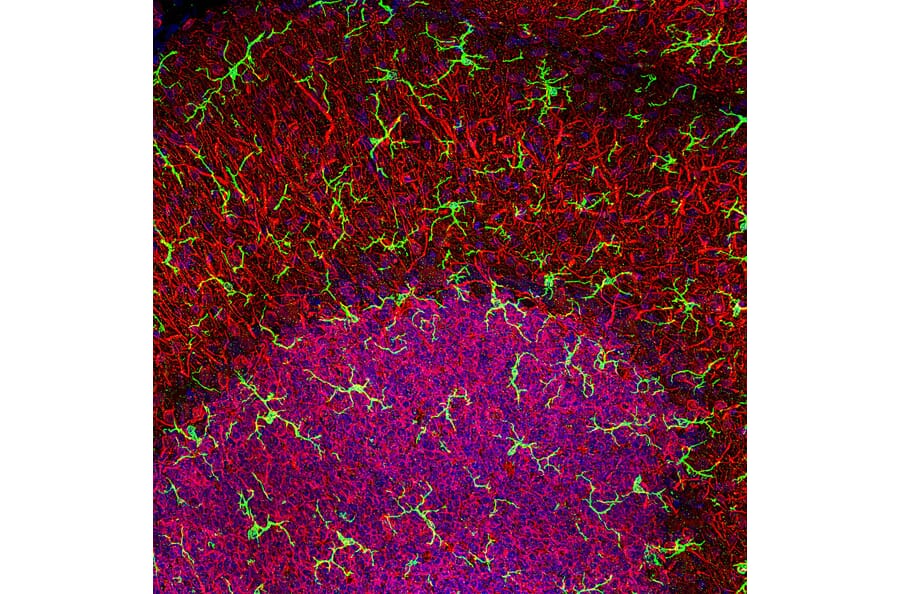

| Brain | Microglia | Synaptic pruning, neuroinflammation regulation | Iba1, P2Y12R, TMEM11913 |

| Heart | Cardiac macrophages | Supporting cardiac tissue repair, aiding in electrical conduction maintenance | CCR2, HLA-DR, TIMD4, GATA614 |

| Gastrointestinal | Mucosal and muscularis macrophages | Supporting gut motility, regulating immune response in the gut, maintaining integrity of gut barrier | Mucosal: CD64, MerTK, CD163, SIRPα, CD20615 Muscularis: CD163, CD206, Retnla, Arg1, Ald1a2, Ccl1716,17 |

| Joints/cartilage | Synovial cells (type A) | Maintaining joint homeostasis, removing debris from synovial fluid | CD68, CD163, Folate receptor β, Translocator protein18 |

| Kidney | Renal-resident macrophages | Supporting glomerular filtration, regulating phagocytosis of immune complexes | CD74, CD81, C1q19 |

| Liver | Kupffer cells | Detoxifying blood, removing pathogens and debris, and regulating lipid metabolism | CLEC4F, VSIG420 |

| Lung | Alveolar macrophages | Regulating immune response to inhaled particles, aiding in lung tissue repair | CD11c, MARCO, CD169, PPARγ, FABP4, EGR221 |

| Serous cavities | Peritoneal macrophages | Removing pathogens and debris from serous fluids, regulating inflammatory response within cavities | GATA6, CSF1R, CD10222 |

| Skin | Langerhans cells | Antigen presentation, immune surveillance, regulating local immune responses in the epidermis | CD1a, Langerin, E-cadherin23 |

Table 1: Key features of tissue-specific macrophages. Note that while many of the above markers are useful for highlighting the cell type indicated, the marker is rarely exclusively expressed in that cell type.

Figure 5: IHC of rat cerebellum stained with rabbit anti-Iba1 (A104332) in green and anti-MAP2 in red. Nuclei are stained by DAPI in blue.

Figure 6: IHC of FFPE human kidney stained with monospecific mouse anti-C1q [C1QA/2956] (A250164).

A further classification relates to the activation state of macrophages in a given time and location, also termed macrophage polarization. Macrophage polarization is a spectrum, with classically activated (M1) macrophages at one end, and alternatively activated (M2) macrophages at the other. Polarization is not fixed, with macrophages capable of changing activation states depending on changes in their local environment.24

Broadly, M1 macrophages are involved in pro-inflammatory responses, releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-12 and TNFα, producing reactive nitrogen and oxygen species, and promoting a Th1 response.25 M1 macrophages are activated by microbial presence (e.g. lipopolysaccharide (LPS)), toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands and interferons. In contrast, M2 macrophages mediate anti-inflammatory responses and tissue repair, induced by exposure to parasites and certain cytokines including IL-4.25 In turn, they produce anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4, IL-10, IL-13 and TGF-β and promote a Th2 response. The two states can be thought of as reflecting the progression of response to an infection: first, M1 macrophages mediate inflammation to fight infection, followed by being induced to a repair-focused M2 phenotype.26

Though the M1 and M2 extremes can be induced in vitro, the situation in vivo is more complex, with many tissues harboring M1 and M2 macrophages simultaneously, and the phenotypes of most macrophages reflecting somewhere between the two extremes. Nonetheless, skewing towards M1 or M2 can occur under both physiological conditions (e.g. pregnancy) and pathological (e.g. allergies, infection, cancer).25

Table 2 illustrates important features of M1 and M2 macrophages, including key markers, inducers and signaling molecules.

| Characteristic | M1 | M2 |

|---|---|---|

| Markers | NOS2, TLR2, TLR4, CD80, CD86 | CD115, CD206, PPARγ, ARG1, CD163, CD301, Dectin-1, PDL2, Fizz1 |

| Induced by | IFNγ, LPS, GM-CSF | Helminth, IL-4, IL-13, M-CSF |

| Secreted Cytokines and Chemokines | IL-12, IL-23, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-8, IL-6, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, CCL5 | IL-10, IL-4, IL-13, TGF-β, CCL17, CCL22 |

| Transcription Factors | STAT1, IRF5, KLF6, NF-κB, SOCS1, JunB | STAT6, IRF4, SOCS3, KLF4, PPARγ, c-Myc, JMJD3 |

Table 2: Common features of M1 and M2 polarized macrophages.

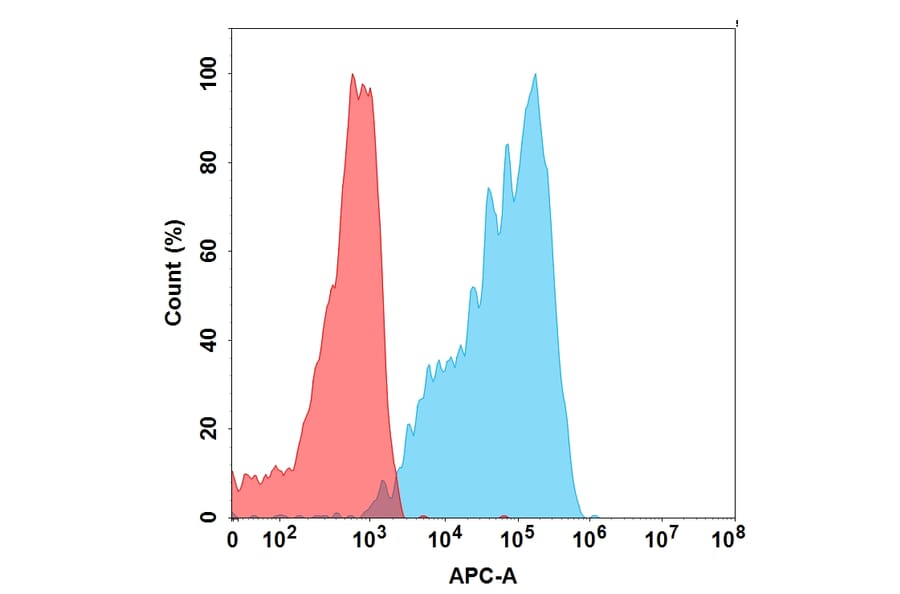

Figure 7: Flow cytometry of human peripheral blood cells stained with APC-conjugated mouse anti-CD86 [BU63] (A85993).

Figure 8: IHC of FFPE human lymph node stained with monospecific APC-conjugated mouse anti-CD163 [M130/2162] (A250604).

M2 Macrophage Subdivisions

M2 macrophages are now recognized as actually comprising multiple subsets: M2a, M2b, M2c, M2d. These all express IL-10, but otherwise can express different cell surface markers and cytokines:27

Figure 9: Flow cytometry of CCR2-transfected Expi293 cells stained with APC-conjugated recombinant humanized anti-CCR2 (A318875).

Figure 10: IHC of FFPE human breast cancer tissue stained with recombinant rabbit anti-VEGFA [R391] (A121422).

Many cancers are highly populated by tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). TAMS are a distinct class of macrophage that can bear both pro- and anti-tumor properties. Pro-tumor TAMs are exploited by cancer cells to promote tumor growth and sustain the tumor microenvironment, associated with a poor patient prognosis, while anti-tumor TAMs can be activated to engage in cytotoxicity of cancer cells, making them a target for cancer therapies.28,29

TAMs can have complex origins and phenotypes, deriving from both circulating monocytes and tissue-resident macrophages. Though TAMs do not align perfectly with the M1-M2 dichotomy that is used to classify many other macrophages, TAMs are generally regarded as being M2-like in phenotype, promoting tumorigenesis.30

M2 markers can therefore often be used for TAMs, though ideally markers of TAMs should be correlated with their role in promoting one of the hallmarks of cancer, such as angiogenesis.30,31 Markers for TAMs include MMP2/9, B7-H4, STAT-3, CD163, and CD206.30

CD169+ Macrophage Markers

CD169+ macrophages, also known as sialoadhesin-positive macrophages, are distinct from M1 and M2 macrophages and are found primarily in secondary lymphoid organs such as the spleen and lymph nodes.32 CD169+ macrophages have numerous roles, including in immune tolerance, antigen presentation, phagocytosis and responses to viral infection.

CD169+ macrophage markers include: CD169, F4/80, CD68, and SRA-1.32

TCR+ Macrophage Markers

TCR+ macrophages are a recently identified subclass of macrophages that express T-cell receptors (TCR), molecules necessary for antigen recognition typically found on T-cells.33 TCR+ macrophages are strongly phagocytic, can release the chemokine CCL2, and have been associated with cancer and disease.33,34

TCR+ macrophage markers include: CCL2, ZAP70, LAT, Fyn, and Lck.

Macrophages can be isolated from whole blood (e.g. PBMC isolation), from tissue or tumor homogenates, and stimulated to differentiate from monocytes in vitro. Features of macrophage biology that are commonly studied include cytokine and chemokine production, expression of cell surface markers, and gene expression analysis.

Flow cytometry remains the primary method of studying macrophage populations (as well as the similar mass cytometry, allowing larger panels). Flow cytometry is an ideal technique for quickly characterizing the morphology and protein expression of thousands or millions of cells in a liquid suspension. Using a defined set of markers, how specific macrophage populations are modified in response to a disease state or other challenge can easily be characterized by flow cytometry.

However, as demonstrated in this article, macrophages are an extremely complex cell type with many overlapping markers. Using such an approach will therefore be inherently limiting to the resolution of the study as well as limited by existing knowledge of markers, which may be incomplete.

A less biased approach is to use single cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq), which can profile the transcriptomes of thousands of cells to provide a comprehensive overview of the diversity of cells present in a sample. More advanced approaches and algorithms enable researchers to enrich for rare populations of cells that might otherwise be engulfed by more dominant populations.

![Flow cytometric analysis of human peripheral whole blood stained using Anti-CD11b Antibody [ICRF44] (PE-Cyanine 7) (A121977)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/121/A121977_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC of FFPE of human tonsil stained with monospecific mouse anti-CD68 Antibody [LAMP4/1830] (A250763).](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/250/A250763_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC of FFPE human tonsil stained with recombinant mouse anti-c-Kit [RM359] (A121476).](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/121/A121476_2.png?profile=product_image)

![Flow cytometry of human peripheral blood cells stained with FITC-conjugated mouse anti-CD14 [MEM-15] (A85585)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/85/A85585_84.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC of FFPE human kidney stained with monospecific mouse anti-C1q [C1QA/2956] (A250164)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/250/A250164_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Flow cytometry of human peripheral blood cells stained with APC-conjugated mouse anti-CD86 [BU63] (A85993)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/85/A85993_361.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC of FFPE human lymph node stained with monospecific APC-conjugated mouse anti-CD163 [M130/2162] (A250604)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/250/A250604_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC of FFPE human breast cancer tissue stained with recombinant rabbit anti-VEGFA [R391] (A121422)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/121/A121422_1.png?profile=product_image)