Kai Boon Tan, PhD | 5th June 2025

GABAergic neurons are inhibitory neurons that produce and release the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).1 These neurons are critical in balancing neural circuits by inhibiting excitatory signals, thereby orchestrating neural activity.2,3 Dysregulation of GABAergic function is linked to epilepsy,4,5 anxiety disorders,6,7 schizophrenia8,9 and autism spectrum disorders,10–12 making GABAergic neurons a major focus of neuroscience research.

Studying GABAergic neurons often requires specific molecular markers, such as glutamate decarboxylase (GAD65/67), vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT), GABA transporter 1 (GAT-1) and GABA itself. This guide highlights the most widely used pan-GABAergic neuron markers for characterizing and analyzing GABAergic neurons across applications such as IHC and ICC/IF. For markers of GABAergic cortical interneurons such as parvalbumin and somatostatin, see our Interneuron Markers page. Below are examples of how GABAergic neuron markers can be used in neuroscience research:

| Molecular Marker | Protein Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| GABA | Neurotransmitter | The primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the nervous system. |

| GAD65, GAD67 | Enzymes | Enzymes essential for GABA biosynthesis. |

| VGAT | Transporter | Transporter that transports GABA from the cytoplasm into synaptic vesicles. |

| GAT1 | Transporter | Transporter responsible to the reuptake of GABA from the synaptic cleft back into presynaptic neurons. |

Table 1: Summary of common molecular markers used to characterize GABAergic neurons.

GABAergic neurons play a crucial role in brain activity by reducing excitatory neuron activity, thus maintaining the balance between excitation and inhibition essential for proper brain function.13 They achieve this by releasing GABA into the synaptic cleft, where it binds to the specific GABA-A and GABA-B receptors on neighboring neurons.14–16 Activation of these receptors causes chloride ions to influx and potassium ions to efflux, leading to hyperpolarization of the postsynaptic neuron and rendering it less likely to fire an action potential.

GABAergic neurons are widely distributed across the nervous system,1 including the cerebral cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, hypothalamus, spinal cord and peripheral nervous system, such as sensory ganglia17 and vagus nerve.18 They are particularly important for controlling the flow of information, synchronizing neural networks, and preventing excessive neuronal firing.1,13 In the cerebral cortex, GABAergic interneurons modulate the activity of excitatory glutamatergic neurons, contributing to the fine-tuning of behaviors, motor control, mood and sleep.13,19

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. Its main function is to reduce neuronal excitability, thereby maintaining the balance between neural excitation and inhibition. When GABA binds to GABA receptors, it typically results in the influx of chloride ions into the neuron (via GABA-A receptors) or the efflux of potassium ions (via GABA-B receptors), ultimately making the neuron less likely to fire an action potential.15,16,20 GABA's inhibitory action is terminated by reuptake into neurons and glial cells via GAT1, where it is then metabolized.21

Although the presence of GABA definitively marks a neuron as GABAergic, direct immunostaining for GABA is technically challenging. GABA is a small molecule that lacks firm anchorage to cellular structures, meaning it can be washed out or lost during fixation. Furthermore, producing highly specific antibodies against small, non-immunogenic molecules (called haptens) is inherently more difficult than for large proteins. For these reasons, marking GABAergic neurons tends to rely on the marker proteins described below.

Figure 1: IHC directly against GABA. IHC of neuronal culture stained with GABA in green, surface GABA-A receptors (β2/3 subunit) in red, and DAPI in blue. Right image an enlarged image of a neuronal process. Edited and reproduced from 22.

The glutamate decarboxylases (GADs) are key enzymes responsible for converting glutamate into GABA in GABAergic neurons.23,24 In mammals, GAD exists in two main isoforms, GAD65 and GAD67, named after their molecular weights of 65 kDa and 67 kDa, respectively. GAD65, encoded by the GAD2 gene, is primarily involved in synthesising GABA at synaptic terminals and is dynamically regulated during neurotransmission.25 GAD67, encoded by GAD1, is constitutively active and more widely distributed in the cytoplasm, and is thought to synthesize GABA for other cellular processes such as development and metabolic functions.26

Figure 2: IHC of rat brain tissue stained with Anti-GAD65 Antibody (A12729) in red. Nuclei were stained by DAPI in blue.

Figure 3: IHC of rat eye cells stained with Anti-GAD67 Antibody (A14262) in red. Nuclei were stained by DAPI in blue.

Vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT or SLC32A1) is a protein usually found in the nerve endings of GABAergic and glycinergic neurons. Its primary function is to package and transport GABA and glycine from the neuron cytoplasm into synaptic vesicles.27,28 VGAT is also known as the vesicular inhibitory amino acid transporter (VIAAT) and is the only member of the SLC32 transporter family. VGAT operates as an antiporter to drive the accumulation of GABA and glycine within vesicles via the proton electrochemical gradient generated by vacuolar H+-ATPase.29 Research has also shown that VGAT can transport β-alanine within GABAergic neurons,30 suggesting a broader substrate specificity than previously thought.31

Gamma-aminobutyric acid transporter 1 (GAT1, encoded by the SLC6A1 gene) is a member of the solute carrier 6 (SLC6) family. It is responsible for the reuptake of GABA from the synaptic cleft back into the presynaptic neurons or astrocytes.21 This reuptake process terminates GABAergic signaling, thereby modulating the duration and intensity of inhibitory neurotransmission.32 GAT1 operates through the electrochemical gradients of sodium and chloride ions, with a typical stoichiometry of 2 Na+:1 Cl-:1 GABA per transport cycle.33 During the transport cycle, GAT1 undergoes conformational changes and enables the sequential binding and release of ions and GABA, ensuring efficient removal of GABA from the synaptic cleft.33,34

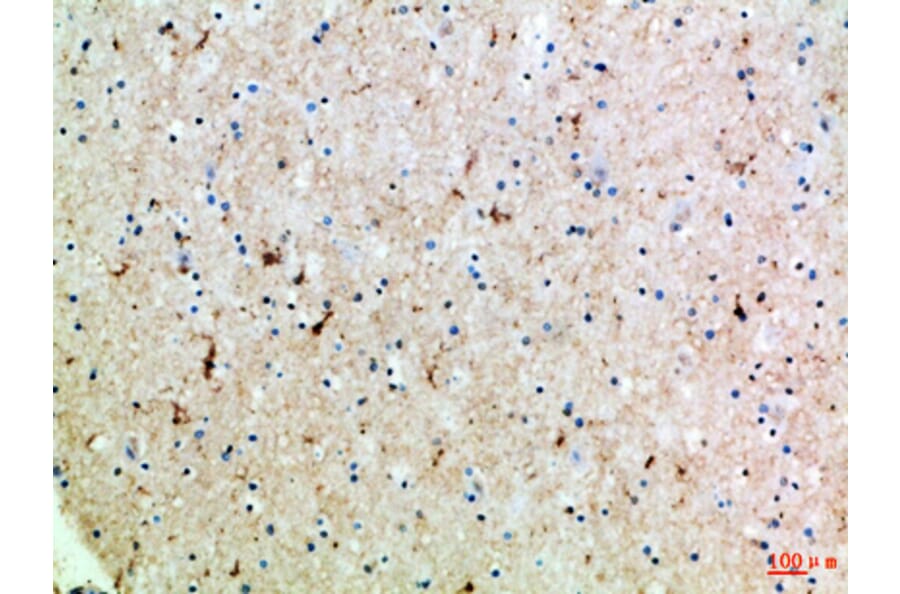

Figure 4: IHC of human brain tissue stained with Anti-SLC6A1 Antibody (A96733).