Heather Van Epps, PhD | 2nd July 2025

Basophils are granulocytic, histamine-producing cells that have a critical role in IgE-dependent allergic hypersensitivity and in immune responses to helminth infection. Although basophils were first described by Ehrich in 1879, more than seven decades passed before their essential role in histamine production and hypersensitivity was definitively demonstrated.1

Basophils—rare cells that account for fewer than 1% of circulating immune cells—are probably best known for their role in hypersensitivity reactions and protection against parasitic infections, but they are now appreciated to be multifunctional cells with roles in other processes including type 2 immunity, autoimmunity, malignancy, and tissue repair.1-4 Basophils — along with developmentally and functionally related mast cells — are key therapeutic targets in the treatment of allergic disorders.5

Like most immune cells, identification of basophils relies mostly on flow cytometry, as well as immunofluorescence (IF) and immunohistochemistry (IHC). These techniques facilitate study of the location and function of basophils in health and disease; for example, tracking basophil tissue infiltration and cytokine production during allergic inflammation or helminth infection. More recently, techniques like multiplex imaging have facilitated study of immune cells within specific spatial contexts.

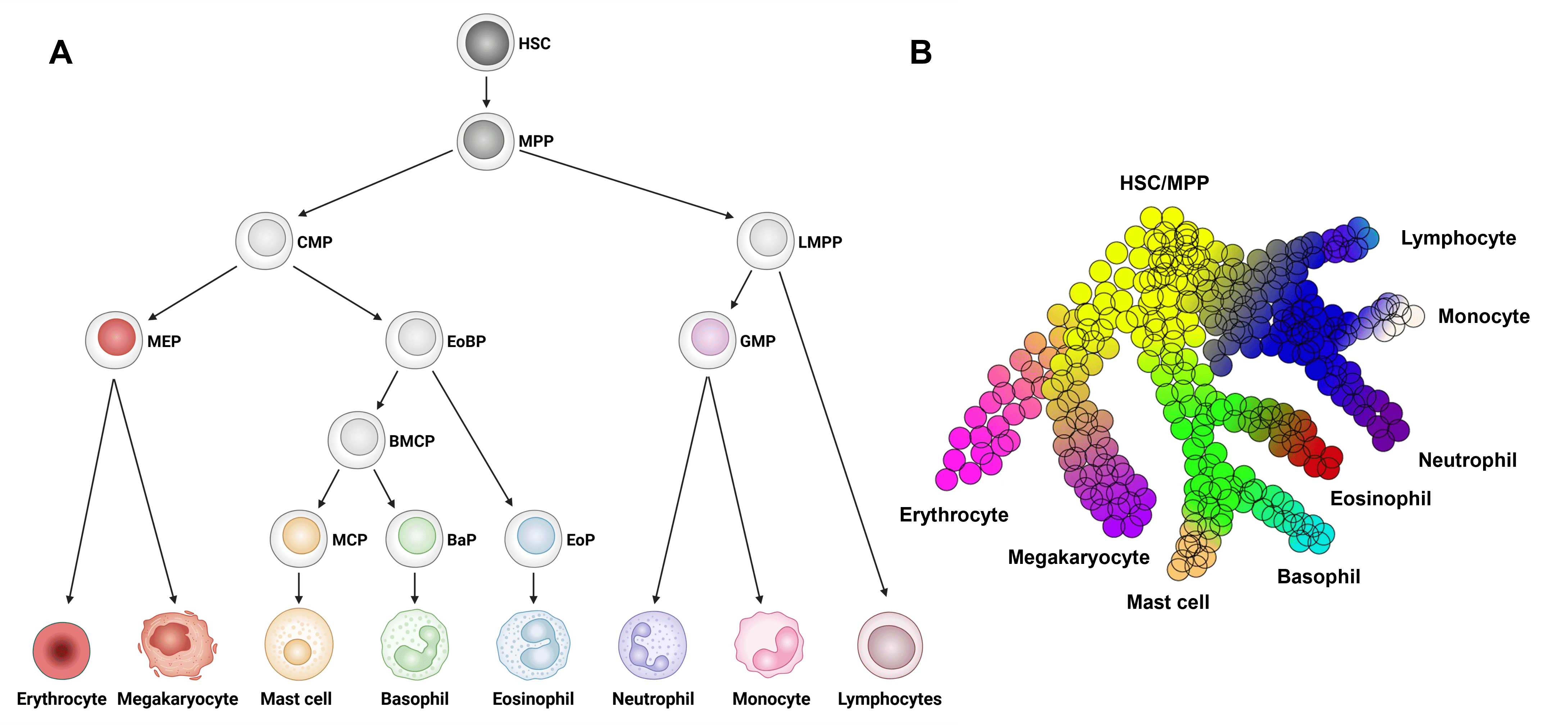

Basophils differentiate from hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) in the bone marrow, passing through increasingly committed stages of development, most of which are shared by bone marrow-derived mast cells.1 Most visual representations of basophil differentiation depict passage through a series of discrete, homogenous progenitor populations, but it is now clear that the process of basophil differentiation is a gradual, continuous process of gene expression changes that culminates in commitment to the basophil lineage (reviewed in 2).

Classically, all granulocytic populations (basophils, mast cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils) in mice arise from GMPs, downstream of common myeloid precursor cells (CMPs; Figure 1A). However, more recent single cell and transcriptomic data suggest that basophils, mast cells, and eosinophils arise from eosinophil-basophil progenitors (EoBPs) that differentiate from CMPs, whereas neutrophils arise from GMPs, downstream of lympho-myeloid primed progenitors (LMPPs; Figure 1B).2 The literature remains inconsistent in this regard, however, and many models of basophil/mast cell ontogeny still depict GMPs as a common progenitor for all granulocytes.

Figure 1: Basophil development from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). A, Model of HSC development to basophils and other major immune cell types. B, Continuous model of hematopoietic differentiation based on single cell RNAseq analysis. BaP, basophil progenitor; BMCP, basophil/mast cell progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; EoBP, eosinophil/basophil progenitor; EoP, eosinophil progenitor; GMP, granulocyte/macrophage progenitor; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; LMPP, lympho-myeloid primed progenitor; MCP, mast cell progenitor; MEP, megakaryocyte/erythrocyte progenitor; MPP, multi-potential progenitor. Edited and reproduced under CC BY 4.0 from 2.

Further downstream, various populations of basophil/mast cell precursors have been described, including basophil mast cell common progenitors (BMCPs), pre-basophil/mast cell progenitors (pre-BMPs), and pro-basophil and mast cell progenitors (pro-BMC).2,5,7 E-cadherin has been proposed as a key marker of bipotent basophil/mast cell progenitors in mice.6 Basophil and mast cell lineages then diverge, and several populations of basophil-committed precursor cells have been described, including basophil progenitors (BaPs), pre-basophils, and transitional basophils (tBaso).1,2,5,7

Phenotypic markers of bipotent and basophil-committed progenitors are shown in Table 1.

| Category | Cell Type | Tissue | Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bipotential progenitor for basophils and mast cells | Pre-BMP | Bone marrow | Lin− Sca-1− cKit+ CD34+ FcγRII/IIIhi FcεRIα+ |

| Pro-BMP | Bone marrow | Lin− Sca-1− cKit+ CD34+ FcγRII/IIIhi E-cadherinhi FcεRIα+ | |

| BMCP | Spleen, bone marrow | Lin− cKit+ CD34+ FcγRII/IIIhi Integrin β7hi | |

| Basophil-committed progenitors | BaP | Bone marrow | Lin− cKit− CD34+ FcεRIα+ |

| Pre-basophil | Bone marrow | CD200R3+ cKit− CLEC12Ahi (FcεRIαhi) | |

| tBaso | Bone marrow | Lin− cKit− CD34− CD200R3+ FcεRIαhi | |

| Mast cell-committed progenitors | MCP | Spleen, bone marrow | Lin− Sca-1− cKit+ Ly6C− FcεRIα− CD27− Integrin β7hi IL-33R+ |

| Small intestine | Lin− CD45+ FcεRIαlo CD34+ Integrin β7+ |

Table 1: Markers of the late stages of basophil and mast cell development. Adapted from 2.

Additional markers of basophil precursor cells include high levels of CD371 (CLEC12A) and the chemokine receptor CXCR4, which is required for retention of precursor cells in the bone marrow (Table 2).8,9 These markers are useful for distinguishing basophil precursors from mature basophils, but again, they are not unique to basophils. For example, CXCR4 is also expressed by T cells and B cells and has a similar role in bone marrow retention of these populations.

| Pre-BMP | Pre-Basophil | Basophil | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Bipotent progenitor for basophils and mast cells | Unipotent basophil progenitor | Mature basophil |

| Surface marker profile | Lin- Sca-1- c-Kit+ CD34+ FcγRII/IIIhi FcεRIα+ (CLEC12Ahi) | CLEC12Ahi CD9lo (FcεRIαhi CD49bint) | CLEC12Alo CD9hi (FcεRIαlo CD49bhi) |

| CXCR4 expression | Unknown | High (reduced after IL-3 stimulation) | Low |

| Tissue localization | Mainly in bone marrow | Mainly in bone marrow | Bone marrow and periphery |

| Proliferative capacity | High | High | Little or none |

| Response to stimuli | Unknown | Stronger response to non-IgE stimulation (IL-3, IL-18, IL-33, LPS etc.) | Stronger response to IgE or allergen stimulation |

Table 2: Key makers and functional features of pre-BMP, pre-basophils, and mature basophils. Adapted from 2.

Figure 2: Flow cytometry analysis of Expi293 cells transfected with human CLEC12A (blue) or irrelevant protein (red) stained with Recombinant Anti-CLEC12A Antibody [DM165] - BSA and Azide free (A318544).

Figure 3: Flow cytometry of human peripheral blood stained with Anti-Integrin alpha 2 Antibody [AK7] (PE) (A86853) (anti-CD49b).

The full details of basophil lineage commitment are incompletely understood, particularly in humans, and this remains an active area of investigation.2,5,10

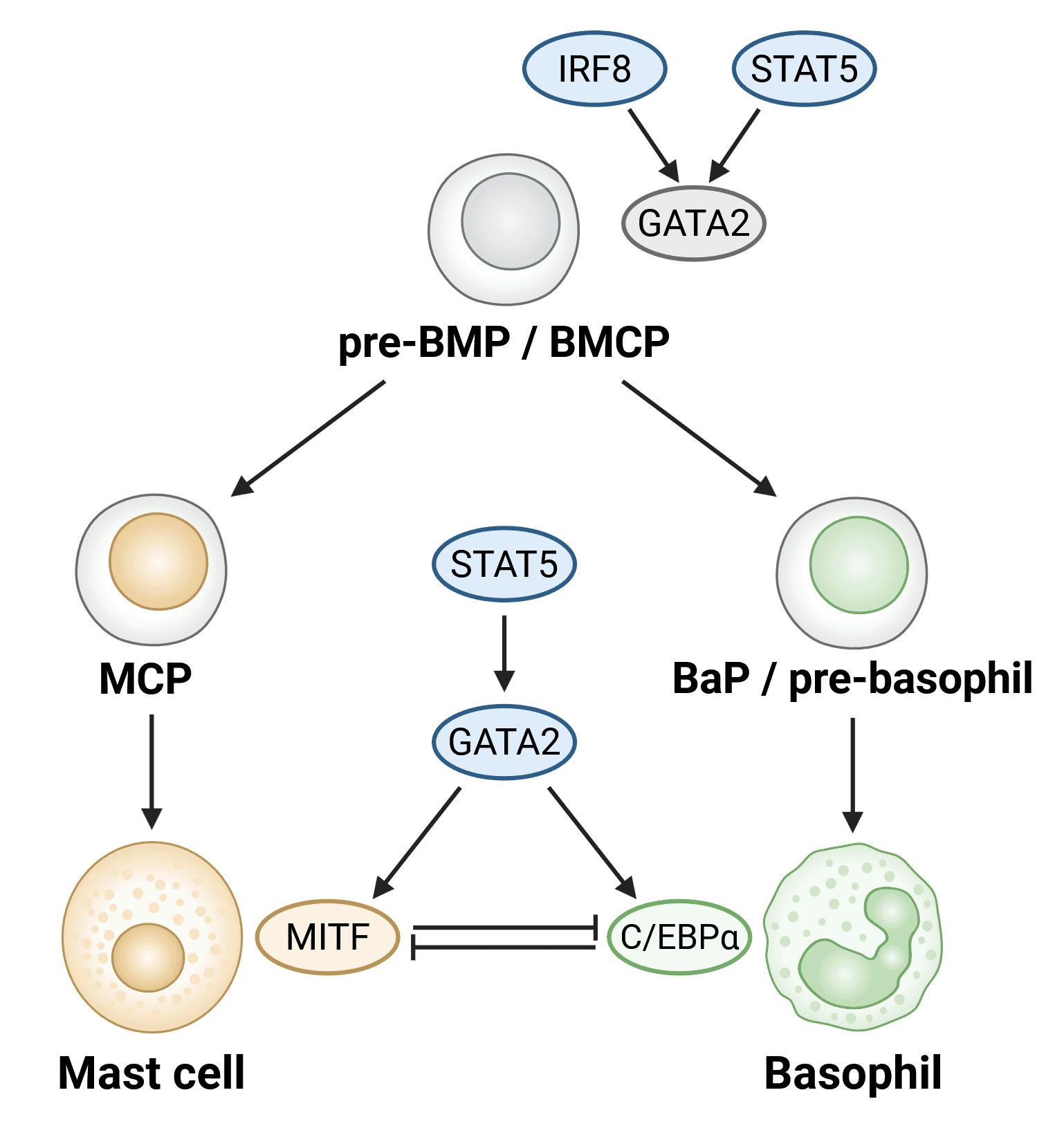

Basophil development is orchestrated by the activity of three key transcription factors: STAT5, GATA-2, and C/EBPα (Figure 4). Direct reciprocal inhibition of C/EBPα and the canonical mast cell transcription factor MITF is a key mechanism that determines the downstream fate of bipotent basophil/mast cell progenitors.10

Figure 4: Transcription factors involved in basophil development. Transcription factors are shown in ovals. Upregulation of GATA2 as a result of increased STAT5 and IRF8 activity is likely involved in the generation of common progenitors of mast cells and basophils (pre-BMPs/BMCPs). STAT5-GATA2-C/EBPα signaling is needed to generate basophils, while the STAT5-GATA2-MITF pathway generates mast cells. BMCP, basophil/mast cell progenitor; Pre-BMP, pre-basophil/mast cell progenitor; BaP, basophil progenitor; MCP, mast cell progenitor. Adapted from 2.

Like most immune cell populations, basophils are identified by expression of a combination of surface markers, and no marker is exclusive to this cell population. As such, definitive identification of these cells depends on the expression (or absence) of an array of surface markers.

Markers commonly used to identify basophils at steady-state include CD123, the alpha subunit of the interleukin (IL)-3 receptor—a cytokine essential for basophil development, proliferation and survival—and the high-affinity receptor for IgE (FcεRI).11 IgE-mediated cross-linking of FcεRI induces potent basophil activation and degranulation, and this is a key process underlying IgE-mediated diseases such as allergic asthma and atopic dermatitis. Both CD123 and FcεRI are also expressed by mast cells and monocytes, and these markers are expressed singly by many other immune and non-immune cell populations.

Additional markers that distinguish mature basophils from their precursor counterparts, include high levels of the integrin CD49b (also expressed by NK cells, monocytes, platelets, and epithelial cells) and the tetraspanin protein CD9, which associates with FcεRI to promote degranulation (Table 2).12

In mice, expression of the granule serine protease Mcpt-8 is unique to mature basophils and is frequently used as a basophil-specific marker as well as a means to deplete or track these cells in vivo (e.g. using Mcpt-8-Cre/diphtheria toxin depletion or Mcpt-8-GFP mouse models).2

Steady-state basophil markers:

Figure 5: Flow cytometry analysis of human peripheral blood stained with Anti-IL3RA/CD123 Antibody [6H6] (Biotin) (A85735).

Figure 6: IF of MOLT-4 cells stained with Anti-CD9 Antibody [SPM547] (A250540).

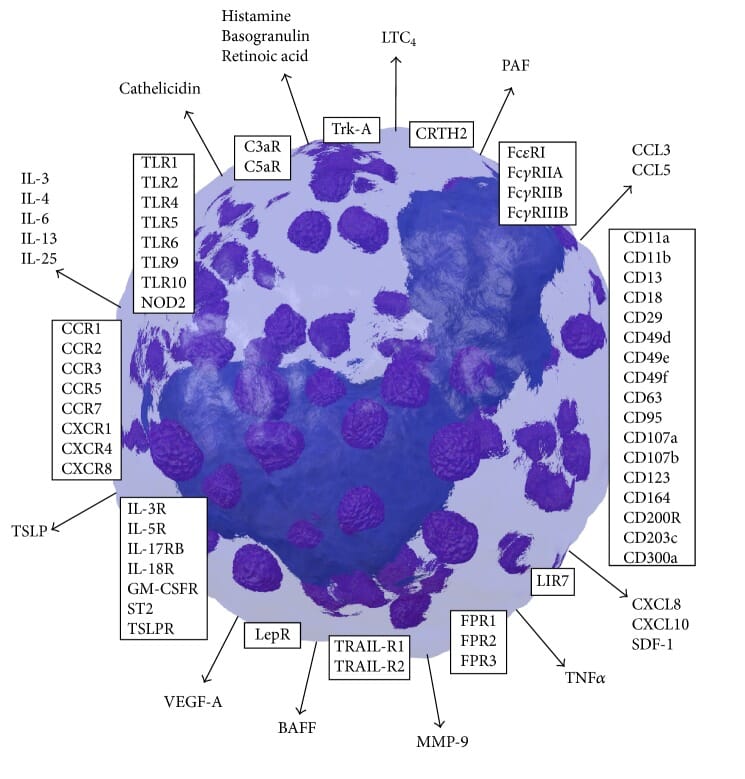

Basophils express a host of other surface proteins, including pattern recognition receptors (e.g. Toll-like receptors [TLRs]), cytokine and chemokine receptors, and other immunoglobulin receptors, that can be used for studying basophils in vitro and in vivo in different contexts (Figure 7).1

Figure 7: Basophil surface markers (boxes) and secreted factors (arrows). Reproduced under CC BY 4.0 from 1.

Sample flow cytometry gating strategies for identification of basophils are shown in Figure 8, and key differences between mouse and human basophil markers are shown in Table 3.13

Figure 8: Strategies for identification of basophils by flow cytometry. 13 different gating strategies are shown following initial gating by FSC, SSC and CD45 expression (black arrows). Reproduced under CC BY 4.0 from 13.

| Phenotypic Marker | Human Basophil | Mouse Basophil |

|---|---|---|

| FcεRI | ++ | ++ |

| FcγRIIA | + | – |

| FcγRIIB | + | + |

| FcγRIIIA | – | + |

| FcγRIIIB | ± | – |

| CD63 | + | + |

| CD203c | + | + |

| IL-3Rα (CD123) | ++ | ++ |

| GM-CSFRα (CD116) | + | + |

| IL-5Rα (CD125) | + | NI |

| TSLPR | – | + |

| IL-33R (ST2) | + | + |

| CCR1 | + | NI |

| CCR2 | ++ | + |

| CCR3 | ++ | ± |

| CCR5 | + | – |

| CXCR1 | ++ | NI |

| CXCR2 | + | + |

| CXCR4 | + | + |

| CRTH2 | ++ | + |

| CD200R | + | + |

| CD300a | + | + |

| CD300c | + | + |

| CD300f | + | + |

| PD-L1 | + | NI |

| VEGFR2 | + | NI |

| NRP1/2 | + | NI |

| TrkA | + | NI |

Table 3: Surface markers of human and mouse basophils. +, expressed; ++, highly expressed; –, not expressed; ±, expressed under certain circumstances; NI, not investigated. Adapted from 20.

Basophils can be activated by a wide array of stimuli, including immunoglobulins (particularly IgE), cytokines and chemokines, complement, and bacterial products:1

Immunoglobulins

Cytokines, growth factors

Bacteria-derived products

Intracellular basophils makers, including the ectoenzyme CD203c and transmembrane protein CD63 (LAMP-3),14,15 are rapidly redistributed to the cell membrane upon activation.1,16 The redistribution of intracellular proteins to the surface of basophils upon activation is often assessed using the flow-cytometry-based basophil activation test (BAT), which is also used for the clinical diagnosis of IgE-mediated allergic conditions.17 Detection of intracellular markers is often used in combination with surface makers to identify activated basophils.

Markers of basophil activation:

Once activated, basophils rapidly release intracellular granules containing histamine and other soluble mediators of allergic inflammation (e.g. leukotriene C4 [LTC4] and platelet-activating factor [PAF]), as well as proteases, cytokines, chemokines, and lipid mediators that modulate the effector functions of other immune cell populations (Figure 7).

Figure 9: Flow cytometry analysis of IgE-activated peripheral blood stained with Anti-CD63 Antibody [MEM-259] (A85976).

Figure 10: Flow cytometry analysis of human basophils in IgE-activated whole blood stained with Anti-CD203c Antibody [NP4D6] (APC) (A86532).

In 2018, basophils were identified in the fetal mouse lung, residing in close proximity to alveoli and type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2). Lung basophils (often called rBasos) are important for the development and function of alveolar macrophages; in mice, inducible depletion of Mcpt8+ basophils results in decreased alveolar macrophage numbers and function.18 rBasos have also been shown to promote the resolution of lung inflammation by inducing an M2-like phenotype in alveolar macrophages and dampening the activity of ILC2 cells.16,19

Lung-resident basophils persist in the mature mouse lung and can be distinguished from their circulating counterparts by high expression of receptors for the cytokines IL-33 (ST2, IL-33R) and GM-CSF (CSF2RB), which are instrumental in inducing the lung-specific gene expression profile in these cells.18 Whether these cells arise from HSCs in bone marrow progenitors or from yolk sac-derived erythro-myeloid progenitors (EMPs), or both, is not yet clear.5

Basophils adopt different functional and phenotypic properties depending on the surrounding cytokine milieu, with distinct roles for IL-3 or thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) in mice.20-23 Both are basophil growth factors that expand mature and precursor basophil populations in vivo, but studies using receptor knock-out mice have shown that neither is strictly essential for basophil development.2,5,20 The impact of TSLP on human basophils remains uncertain, with some studies showing that human basophils do not express the TSLP receptor nor respond to TSLP stimulation.20-22

Functionally, IL-3-elicited basophils are more adept at IgE-dependent degranulation, and are essential for anti-parasite responses, which are dampened in mice lacking IL-3.5 By contrast, TSLP-elicited basophils are less responsive to IgE-antigen complexes but excel at IL-4 and IL-13 production and express higher levels of cytokine receptors (IL-3, IL-18, IL-33).1,2,5 In line with this functional specialization, IL-3-dependent basophils are fundamental to IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions, whereas TSLP-elicited basophils have a central role in chronic type 2 inflammatory conditions such as atopic dermatitis, eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), and allergic rhinitis.3,5,22

Most TSLP-elicited basophils in mice express low levels of CLEC12A and high levels of CD49b and CD9, similar to the typical phenotype of mature basophils.9 Characteristics and markers of IL-3- and TSLP-elicited basophils are outlined in Table 4.

| Marker | IL-3-elicited basophils | TSLP-elicited basophils |

|---|---|---|

| FcεRI | High | Med-High |

| CLEC12A | High | Low |

| IL-33R (ST2) | Low | High |

| IL-18R | Low | High |

| CD11b | High | Low |

Table 4: Cell surface markers on IL-3-elicited or TSLP-elicited basophils.

Diagrams created with BioRender.com.

![Flow cytometry - Recombinant Anti-CLEC12A Antibody [DM165] - BSA and Azide free (A318544)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/318/A318544_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Flow cytometry - Anti-Integrin alpha 2 Antibody [AK7] (PE) (A86853)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/86/A86853_930.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Flow cytometry - Anti-IL3RA/CD123 Antibody [6H6] (Biotin) (A85735)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/85/A85735_190.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IF - Anti-CD9 Antibody [SPM547] (A250540)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/250/A250540_2.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Flow cytometry - Anti-CD63 Antibody [MEM-259] (A85976)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/85/A85976_346.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Flow cytometry - Anti-CD203c Antibody [NP4D6] (APC) (A86532)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/86/A86532_705.jpg?profile=product_image)