Kay Shigemori, PhD | 7th August 2025

Plasma cells, also known as plasma B cells, are terminally differentiated non-proliferative B cells that produce and secrete a single type of immunoglobulin (Ig) or antibody. Required for short- and long-term humoral immunity, plasma cells play a central role in immune responses by secreting antigen-specific antibodies that neutralize pathogens or mediate opsonization and complement activation.1-4

There are unique sets of surface and intracellular cell markers expressed by plasma cells that are frequently applied to evaluate immune responses following vaccination and infection, with key plasma cell markers including CD138, CD38, CD27 and CD319. Plasma cells lack expression of pan-B cell markers like CD19 and CD20, but may express some B cell markers such as B220 (a CD45 isoform) in mice. For clonal identification, intracellular immunoglobulins are often used in combination with surface markers to identify a specific population of plasma cells.4

Plasma cells develop from activated B cells via plasmablast stages, with each developmental stage bearing its own characteristic markers (Figure 1, Table 1).6

Figure 1. Plasma cell differentiation and maturation

| Activated B cell | Pre- plasmablast | Blimp1int plasmablast | Blimp1int plasma cell | Blimp1high plasma cell | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation | Cycling | Cycling | Cycling | Sessile | Sessile |

| Lifespan | Days | Days | Days | Days | Months-years |

| Location | Spleen, LN, PP | Spleen, LN, PP | Spleen, LN, Blood | Spleen, LN, Blood, bone marrow | Spleen, LN, LP, bone marrow |

| Markers | B220high MHC-IIhigh CD138- CXCR4- | B220high MHC-IIhigh CD138- CXCR4- | B220int MHC-IIint CD138+ CXCR4+ | B220int MHC-IIint CD138+ CXCR4+ | B220low MHC-IIlow CD138+ CXCR4++ |

| Transcription factors | Pax5high Bach2+ IRF4+ Blimp1- XBP1low | Pax5low Bach2low IRF4++ Blimp1- XBP1int | Pax5- Bach2- IRF4+++ Blimp1int XBP1high | Pax5- Bach2- IRF4+++ Blimp1int XBP1high | Pax5- Bach2- IRF4+++ Blimp1high XBP1high |

Table 1: Characteristics of different plasma cell developmental stages. LN, lymph nodes; LP, lamina propria; PP, Peyer’s patches. Information adapted from 6.

Once mature, plasma cells are generally present in low numbers in lymphoid organs (<2%–3% of nucleated cells) and are large in size. There are generally two types:

Flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry (IHC) are the two main methods used to identify plasma cells in research and clinical diagnostics. Below, we provide a list of commonly used plasma cell markers in flow cytometry and IHC.

Flow Cytometry Panel

Typically profiling for plasma cells using flow cytometry includes all or a combination of the surface cell markers listed in Table 2. Peripheral blood, bone marrow aspirates or tissue lysate can be used for this method of analysis.7,8

| Marker | Location | Expression in normal plasma cells | Expression in malignant plasma cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD38 | Surface | +++ | +++ |

| CD138 | Surface | + | + |

| CD19/CD20 | Surface | - | - (some aberrantly +) |

| CD45 | Surface | dim | -/dim |

| CD56 | Surface | - | + |

| CD27 | Surface | + | + |

| CD319 (SLAMF7) | Surface | ++ | ++ |

| Kappa/Lambda light chains | Surface | κ⁺ and λ⁺ mix | κ only or λ only |

Table 2: Common markers used in flow cytometry analysis of plasma cells.

Figure 2: Flow cytometry analysis of human peripheral blood stained with Anti-CD38 Antibody [HIT2] (PerCP) (A86187).

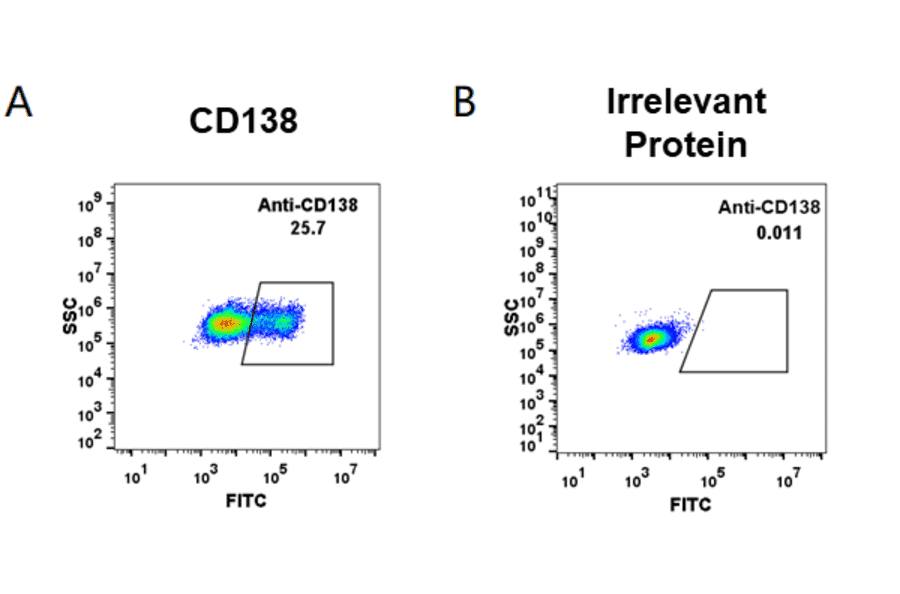

Figure 3: Flow cytometry analysis of HEK293 cells transfected with human CD138 (A) or irrelevant protein (B) stained with Indatuximab Biosimilar - Anti-Syndecan-1 Antibody - BSA and Azide free (A318942).

Immunohistochemistry Markers

IHC is commonly used in detecting plasma cells in tissue sections such as bone marrow biopsies, lymph nodes or extranodal masses. In Table 3 we provide a list of markers commonly used for IHC assessment of plasma cells.

| Marker | Location | Expression in normal plasma cells | Expression in malignant plasma cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD38 | Surface | + | + |

| CD138 | Surface | ++ | ++ |

| MUM1/IRF4 | Nuclear | + | + |

| CD45 | Surface | -/dim | -/dim |

| CD79a | Cytoplasmic | + | + |

| Cyclin D1/BCL1 | Nuclear | - | Positive in some myeloma subtypes |

| Kappa/Lambda light chains | Cytoplasmic | κ⁺ and λ⁺ mix | κ only or λ only |

Table 3: Markers of plasma cells used in IHC.

Figure 4: IF of Raji cells stained with Recombinant Anti-CD79a Antibody [IGA/1790R] (A250790).

Figure 5: IHC of human tonsil tissue stained with Anti-MUM1 Antibody [IHC627] (A324482).

Some specific examples of marker usage in malignancies include:

CD138 (Syndecan-1, SDC1)

CD138, also known as Syndecan-1 (SDC1), is a transmembrane proteoglycan involved in cell adhesion and extracellular matrix remodeling.10,11 It is highly and specifically expressed on the surface of immature B cells and mature plasma cells and is considered a highly specific surface marker for plasma cell identification.12,13 CD138 is widely used in both IHC and flow cytometry, especially in identifying normal and neoplastic plasma cells in bone marrow or tissue sections.14,15 However, CD138 is also expressed on epithelial cells, and its expression can be lost in necrotic regions, which necessitates contextual interpretation in tissue samples.16

CD38

CD38 is a transmembrane ectoenzyme involved in NAD⁺ metabolism and intracellular calcium signalling.17 Plasma cells and multiple myeloma cells exhibit very bright CD38 surface expression as measured by flow cytometry.18 However, CD38 is also expressed on activated T cells and NK cells19,20 and early hematopoietic progenitors,21 so its specificity is limited. In multiple myeloma, CD38 is targeted therapeutically by anti-CD38 antibody, daratumumab, highlighting its relevance beyond diagnostics.22

CD27

CD27 is a co-stimulatory receptor of the TNF receptor superfamily, variably expressed on the surface of B, T and NK cells.23 CD27 is the receptor for its ligand CD70, which is expressed on immune cells and frequently on cancer cells.24 As CD27 is expressed not only in plasma cells, but also in other lymphocytes, it needs to be used in combination with other cell markers for the identification of plasma cells. On B cells, CD27 positivity distinguishes IgG class-switched memory B cells and plasma cells (CD27+) from naïve B cells (CD27-).25 CD27 also plays a role in promoting plasma cell differentiation and IgG secretion.26 Soluble CD27 has been explored as a marker of immune function and prognostic markers for immunologic and oncologic diseases.27,28

Figure 6: IHC of human tonsil stained with Anti-CD27 Antibody [LPFS2/4177] (A250621).

Figure 7: Flow cytometry analysis of human peripheral blood cells stained with Anti-CD27 Antibody [LT27] (PE-Cyanine 7) (A122000).

CD79a

CD79a is the alpha chain of the signaling component of the B cell receptor complex that is expressed over a range of B cell development stages – from early B cell precursors through B cell maturation.29,30 In plasma cells, CD79a remains expressed even after CD19 and CD20 are downregulated.29 It is mainly used in IHC to confirm B-cell lineage, particularly in lymphomas with plasmacytoid features or ambiguous morphology.31 Although CD79a is not exclusive to plasma cells, its persistence in later B-cell stages makes it a supportive marker in the diagnostic panel.32

CD319 (SLAMF7)

CD319, also known as SLAMF7 or CS1, is a surface receptor involved in immune cell adhesion and activation. It is highly expressed on both normal and malignant plasma cells33 and is commonly included in flow cytometry panels, particularly for minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma.33,34 CD319 is also the therapeutic target of anti-SLAM7 monoclonal antibody, elotuzumab, in multiple myeloma.35

Figure 8: Flow cytometry analysis of Expi293 cells transfected with irrelevant protein (A) and human CS1 (SLAMF7; B) stained with Recombinant Anti-SLAMF7/CS1 Antibody [DM9] - BSA and Azide free (A318676).

Figure 9: IHC of human tonsil tissue stained with Anti-SLAMF7 Antibody [SLAMF7/3649] (A249779).

MUM1 (IRF4)

Multiple Myeloma Oncogene 1 (MUM1), also known as IRF4, is a transcription factor essential for the final stages of B-cell differentiation into plasma cells.36 MUM1+ cells are typically located in the light zone of the germinal centre, but not expressed in the highly proliferative cells in the dark zone.37 MUM1 is detectable in the nucleus via IHC and is often utilised in the evaluation of lymph node or bone marrow biopsies for diseases including diffuse large B cell lymphomas (DLBCL) and multiple myeloma.38,39 As MUM1 is expressed not only in plasma cells but also in activated T cells, it should be used in combination with other markers to confirm plasma cell identity.

BLIMP-1 (PRDM1)

B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1 (BLIMP-1) is a zinc-finger transcriptional repressor encoded by the PRDM1 gene and drives the terminal differentiation of B cells into plasma cells.40,41 It suppresses genes that maintain the B-cell program while inducing immunoglobulin secretion genes.40 BLIMP-1 also plays a role in T cell development and can be expressed T cell lineages,42 highlighting the need for the marker to be used in combination for plasma cell identification. BLIMP-1 is typically assessed using western blot, IHC, or RT-PCR (for PRDM1 gene) in research contexts.

XBP1

X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) is a transcription factor involved in the unfolded protein response (UPR), a pathway that is highly active in antibody secretory cells such plasma cells due to their large volume of protein production.43 Activated XBP1 drives expansion of the endoplasmic reticulum and supports antibody production.44,45 While it is an important marker of functional antibody-secreting plasma cell activity, it is not routinely used in clinical diagnostic settings, and is instead more frequently assessed via qPCR (for Xbp1 gene), western blot or RNA-sequencing in research settings.46

CD19 and CD20

CD19 and CD20 are classical B-cell markers that are downregulated during plasma cell differentiation. Their absence is used in flow cytometry to distinguish plasma cells (CD19-/CD20-) from less differentiated B cells (CD19+/CD20+).47 Some myeloma subtypes may aberrantly retain CD19 expression.48,49

CD45

CD45, or leukocyte common antigen, is a tyrosine phosphatase expressed on most hematopoietic cells. In plasma cells, expression is variable – typically expressed in low levels or absent in plasma cells. Its expression pattern is used in flow cytometry to help differentiate between clonal and reactive plasma cell populations.50

CD56 (NCAM)

CD56 is an adhesion molecule that is expressed in low levels or absent on normal plasma cells but is aberrantly expressed in neoplastic plasma cells (multiple myeloma) cells.50 It is routinely included in flow cytometry panels to distinguish clonal from polyclonal plasma cells.

Cyclin D1 (BCL-1)

Cyclin D1, also known as B cell lymphoma 1 (BCL1), is a nuclear cell cycle regulator that controls the transition from G1 to S phase in the cell cycle. Plasma cell neoplasms with the t(11;14) translocation or have increased copies of chromosome 11 express cyclin D1, abnormalities found in multiple myeloma patients.51,52 Cyclin D1 is detected using IHC or fluorescent in-situ hybridisation (FISH) and aids in differentiating cyclin D1⁺ myeloma from other lymphoid neoplasms, such as mantle cell lymphoma.52

Kappa (κ) and Lambda (λ) Immunoglobulin Light Chains

Kappa (κ) and Lambda (λ) are immunoglobulin light chains. In normal plasma cells, both chains would be produced (polyclonal, κ⁺ λ⁺), however neoplastic cells, such as multiple myeloma, plasmacytoma or MGUS cells, tend to produce immunoglobulins with either κ or λ light chains (monoclonality, e.g., κ⁺ only).53 In normal conditions, there is a polyclonal distribution of both chains. Light chain expression is detected by flow cytometry (intracellular staining) or IHC, and monoclonality is a key diagnostic criterion.54

Figure 10: IHC of human tonsil tissue stained with Recombinant Anti-Kappa Light Chain Antibody [rKLC264] (A248973).

Figure 11: IHC of human tonsil tissue stained with Anti-Lambda Light Chain Antibody [LLC/1738] (A248998).

Understanding Immune Responses

Plasma cells have been extensively studied to evaluate durable immune responses following vaccination or infection. For example, the appearance of transient plasmablasts (CD19⁺CD27⁺CD38⁺) in peripheral blood shortly after immunization or during acute infection has been investigated to understand humoral immune responses.55,56 Flow cytometric quantification of plasma cells has provided insights into vaccine efficacy and the longevity of immune responses, most recently exemplified in studies on SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.57 These studies employed extensive flow cytometry panels to profile immune cells from peripheral blood, lymphatic tissues (e.g., bone marrow, spleen), and other relevant organs, allowing dissection of the complex humoral immune response involving plasma cells and other immune subsets.

Clinical Relevance and Therapeutic Targeting

The accurate identification of plasma cells through specific surface and intracellular markers is important for clinical diagnostics and therapeutic targeting, especially for autoimmune diseases and a number of cancers.

Plasma cell markers are critical in the diagnosis of plasma cell neoplasms, including multiple myeloma, solitary plasmacytoma, and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). These diseases occur when the clonal proliferation of plasma cells is uncontrolled, demonstrated by the aberrant expression of plasma cell markers such as CD56 and the loss of CD19 or CD45.58 Discrimination between normal plasma cells and clonal plasma cells at initial diagnosis or minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring is typically done with an extensive flow panel including CD138, CD38, CD45, CD19, CD56, CD27 and CD81.59,60

Additionally, several therapies for multiple myeloma have been developed in the past decade targeting plasma cell surface proteins, including CD38-targeting daratumumab61 and SLAM7 (CD319)-targeting elotuzumab.62 For the clinical adoption of these targeted therapies, the appropriate clinical assessment of the expression of the target proteins needs to be carried out during diagnosis and MRD monitoring with flow cytometry of blood biopsies.

Diagrams created with BioRender.com.

![Flow cytometry - Anti-CD38 Antibody [HIT2] (PerCP) (A86187)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/86/A86187_487.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IF - Recombinant Anti-CD79a Antibody [IGA/1790R] (A250790)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/250/A250790_4.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC - Anti-MUM1 Antibody [IHC627] (A324482)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/324/A324482_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC - Anti-CD27 Antibody [LPFS2/4177] (A250621)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/250/A250621_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Flow cytometry - Anti-CD27 Antibody [LT27] (PE-Cyanine 7) (A122000)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/122/A122000_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Flow cytometry - Recombinant Anti-SLAMF7/CS1 Antibody [DM9] - BSA and Azide free (A318676)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/318/A318676_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC - Anti-SLAMF7 Antibody [SLAMF7/3649] (A249779)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/249/A249779_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC - Recombinant Anti-Kappa Light Chain Antibody [rKLC264] (A248973)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/248/A248973_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC - Anti-Lambda Light Chain Antibody [LLC/1738] (A248998)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/248/A248998_2.jpg?profile=product_image)