Lucas Baumard, PhD | 7th July 2025

Natural killer (NK) cells are large, granular lymphocytes (Figure 1) of the innate immune system that act as a first line of defense against early infection and cellular transformation by directly lysing affected cells with cytolytic molecules.

Unlike T cells and B cells, NK cells do not express clonotypic receptors and therefore do not require prior antigen sensitization to eliminate their target cells. Instead, they express a variety of NK receptors (NKRs), such as the killer immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs), to distinguish healthy “self” cells from cells that are “non-self” or diseased.

NK cell marker expression varies depending on their location in the body and NK cell subset and lineage. The study of the expression of markers associated with NK cell activation can determine developmental stage and the capacity to respond to an infection or tumor.

Figure 1: Morphology of a conventional NK cell in the spleen, shown by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Of note is the very large nucleus (dark grey). Edited and reproduced under CC BY 4.0 from 1.

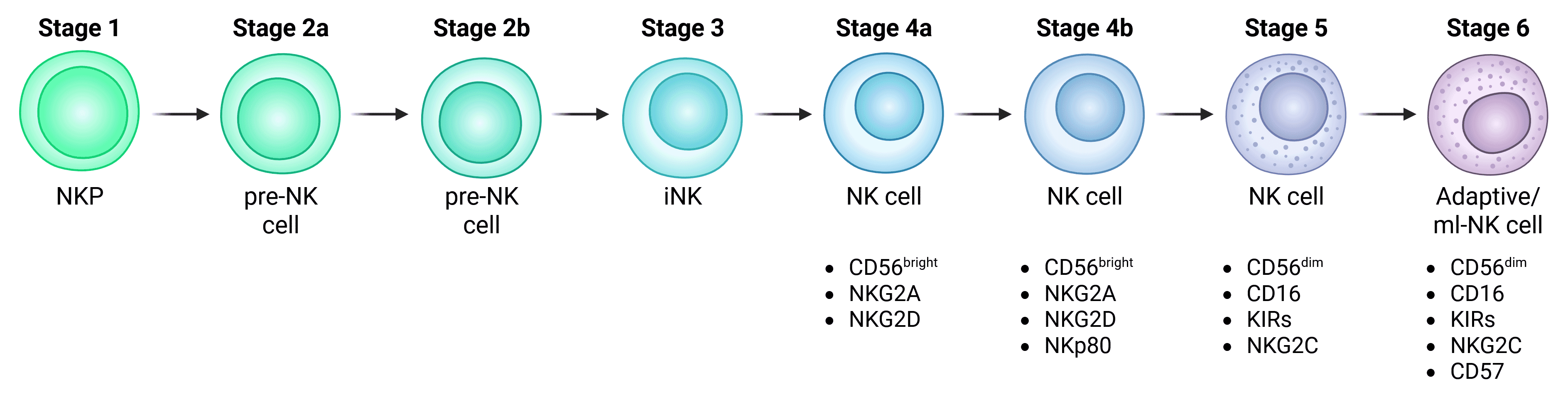

Conventional or circulating NK cells (cNK cells) develop from common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) cells of the bone marrow, which in turn develop from CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) (Figure 2). While a spectrum of NK cell developmental intermediates can be found in the bone marrow, the conventional model suggests that NK cell progenitors finalize development by seeding secondary lymphoid tissues such as the tonsil – although non-lymphoid organs such as the liver has also been seen to host NK cell developmental stages. After precursor differentiation within tissues, mature, functional cNK cells then enter the circulation.2

Figure 2: Development of conventional NK cells. Important markers of functional NK cells are indicated. Note that Stage 6 are depicted as adaptive or memory-like (ml) NK cells, while some suggest that these are distinct populations.

The stages of cNK cell differentiation are complex and incompletely understood, complicated by the suggestion that some subsets along the NK lineage are functionally distinct subsets (see CD56 Expression Determines Major cNK Subsets). Due to this incomplete understanding, there are numerous naming conventions for cNK cell development, where they have been variably described as:

Common markers for these stages and their precursors can be found in Table 1. Some of the most important markers are described in greater detail further below (see CD56 and CD16 Determine Major cNK Subsets and Adaptive NK Markers).

| HSC | LMPP | CLP | NKP Stage 1 | Pre-NK Stage 2a | Pre-NK Stage 2b | iNK Stage 3 | CD56bright Stage 4a | CD56bright Stage 4b | CD56dim Stage 5 | CD56dim Stage 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lin | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| CD34 | + | low | + | + | + | + | +/- | - | - | - | - |

| c-Kit | + | low | + | + | - | + | + | +/low | low/− | low/- | - |

| CD244 | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| CD45RA | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/− | +/− | - | - |

| CD127 | - | - | + | + | + | + | +/- | - | - | - | - |

| CD7 | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| CD10 | - | - | + | + | +/- | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ILR1 | - | - | - | low | - | + | + | +/low | low/- | low/- | low/- |

| CD122 | - | - | - | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| HLA-DR | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| NKp46 (NCR1) | - | - | - | - | - | - | +/- | + | + | + | + |

| NKp30 | - | - | - | - | - | - | +/- | + | + | + | + |

| CD161 | - | - | - | - | - | - | +/- | + | + | + | + |

| NKG2D | - | - | - | - | - | - | +/- | + | + | + | + |

| NKG2A | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | low/- | low/- |

| NKp80 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | + |

| CD56 | - | - | - | - | - | low/- | low/- | ++ | ++ | low | low |

| CD16 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| KIR | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | +/- | + |

| NKG2C | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| CD57 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + |

Table 1: Human NK cell surface markers expressed during distinct developmental stages. ++, high expression; +, moderate expression; low, low expression; –, no detectable expression. Adapted from 3

Using the Stage 1-6 terminology, mature cNK cells emerge at Stage 4 (4a/4b). Commitment to the NK lineage happens incrementally prior to this stage, marked by the expression of key markers. CLP cells are multipotent and can develop into T cells, B cells or other innate lymphoid cells (ILCs).6,8,9 CLP cells destined for an NK fate can be identified by:3

Despite the linearity of the model depicted in Figure 2, NK cell development may be more complex and plastic, including branching development from precursors to different types of functionally mature cNK cells.7

CD56 (NCAM1) is the canonical NK cell marker, and divides NK cells into two main types based on the intensity of CD56 expression:10

CD56 is as an adhesion molecule that is thought to facilitate NK-target cell interactions.13 CD56dim or CD56bright status therefore reflects differences in the homing ability and phenotypes of these stages.11 CD56bright NK cells represent approximately 10% of mature peripheral blood NK cells (though they are the predominant subset in lymph nodes) and develop to full maturity upon expression of the receptor NKp80 at stage 4b.14 The other 90% of cNK cells in the blood of healthy individuals are CD56dim and are thought to develop from CD56bright cells.

Alongside CD56, CD16 is another marker that classically defines mature cNK cells (Figure 3). CD56dimCD16bright cells represent the largest subset in peripheral blood NK cells whilst CD56dimCD16− and CD56−CD16+ are in the minority.15 High levels of CD16 are associated with antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), a common mechanism by which NK cells kill target cells,11 and CD16 is a receptor for the Fc portion of IgG antibodies.16 CD16 is found in different isoforms with CD16a mostly expressed on NK cells but also macrophages and monocytes whereas CD16b is expressed on neutrophils.16,17 CD16 is rapidly downregulated after stimulation.18

Figure 3: CD56 and CD16 expression distinguish NK cell subsets. A, Flow cytometry analysis of NK cell subsets in human peripheral blood based on the relative expression of CD16 and CD56. 1: CD56bright CD16−. 2: CD56bright CD16dim. 3: CD56dim CD16−. 4: CD56dim CD16+. 5: CD56− CD16+. B, Percentages of NK cell subsets compared to the total NK cell population. Edited and reproduced under Creative Commons 4.0 CC-BY from 19.

CD27 is an NK cell marker that has only recently begun to be studied. Most peripheral blood human NK cells are CD27low and this CD27low population shows higher cytotoxicity in vitro, whereas the CD27high population produces more IFN-γ and TNF-α.20 The study authors postulated that the CD27low population represented a more mature, differentiated NK cell.

Figure 4: Flow cytometry analysis of human peripheral blood stained with Anti-NCAM1 Antibody [LT56] (APC) (A86431).

Figure 5: Flow cytometry analysis of human peripheral blood cells stained with Anti-CD16 Antibody [LNK16] (A85767).

NK cells have historically been defined as non-specific cytolytic cells, but recent evidence suggests that some populations of NK cells exhibit adaptive or memory-like traits.3,21 These populations undergo large clonal expansions following re-exposure to viral infection such as CMV.3

Memory-like or adaptive NK cells typically express the CD94/NKG2C receptor for recognizing virally infected cells, although they can also be primed by repeated exposure to consistent cytokine contexts.2 They are also characterized by expression of KIRs (see Inhibitory/activator receptors on NK cells) and CD57 and a lack of CD161, NKp30, and CD7.4

CD57 (B3GAT1) expression has been shown to increase with age22 and is associated with maturing NK cells and CD8+ T cells. CD57 expression also reflects high cytolytic potential, reduced IFN-γ production and increased granzyme expression in NK cells.23,24 CD57+ NKG2C.high NK cells have been shown to increase in number at the onset of infection and to decrease after antigen clearance, albeit less rapidly than other NK subsets, indicating less susceptibility to death.24

Adaptive NK cells are typically CD56dim, though they are a distinct population from the CD56dim stage 5 cNK cells described earlier and may develop from them. They are sometimes considered a terminally differentiated stage 6, though they may also be a distinct population (Figure 2).2,7

Figure 6: Flow cytometry analysis of buffy coat cells stained with Anti-CD57 Antibody [TB01] (A86858).

Figure 7: Flow cytometry analysis of human peripheral blood cells stained with Anti-CD94 Antibody [HP-3D9] (PE) (A86325).

Although cNK cells follow approximately the same developmental progression in humans as in mice, the characteristic markers of each stage can differ. These are illustrated in Table 2.

| Stage | Mouse Markers | Human Markers |

|---|---|---|

| HSC | Lin- c-Kit+ Sca-1+ | Lin- CD34+ CD133+ CD244+ |

| CLP | Lin- c-Kit+ CD122- IL-7Rα+ Sca-1+ Flt-3+ | Lin- CD34+ CD45RA+ CD127+ CD133+ CD244+ |

| NKP | Lin- c-Kit- CD122+ IL-7Rα+/- NKG2D+ 2B4+ | Lin- CD34+ CD45RA+ CD122+ CD38+ CD244+ |

| Immature / M1 | NK1.1+ NKp46+ CD122+ NKG2D+ CD27+ CD11b- | CD56bright CD122+ CD16- CD57- KIR- |

| Transitional / M2 | NK1.1+ NKp46+ CD122+ NKG2D+ CD27+ CD11b+ | CD56dim CD122+ CD16+ CD57- KIR+ |

| Mature / M3 | NK1.1+ NKp46+ CD122+ NKG2D+ CD27- CD11b+ | CD56dim CD122+ CD16+ CD57+ KIR+ |

Table 2: Distinct markers in mouse and human NK cells. Adapted from 6

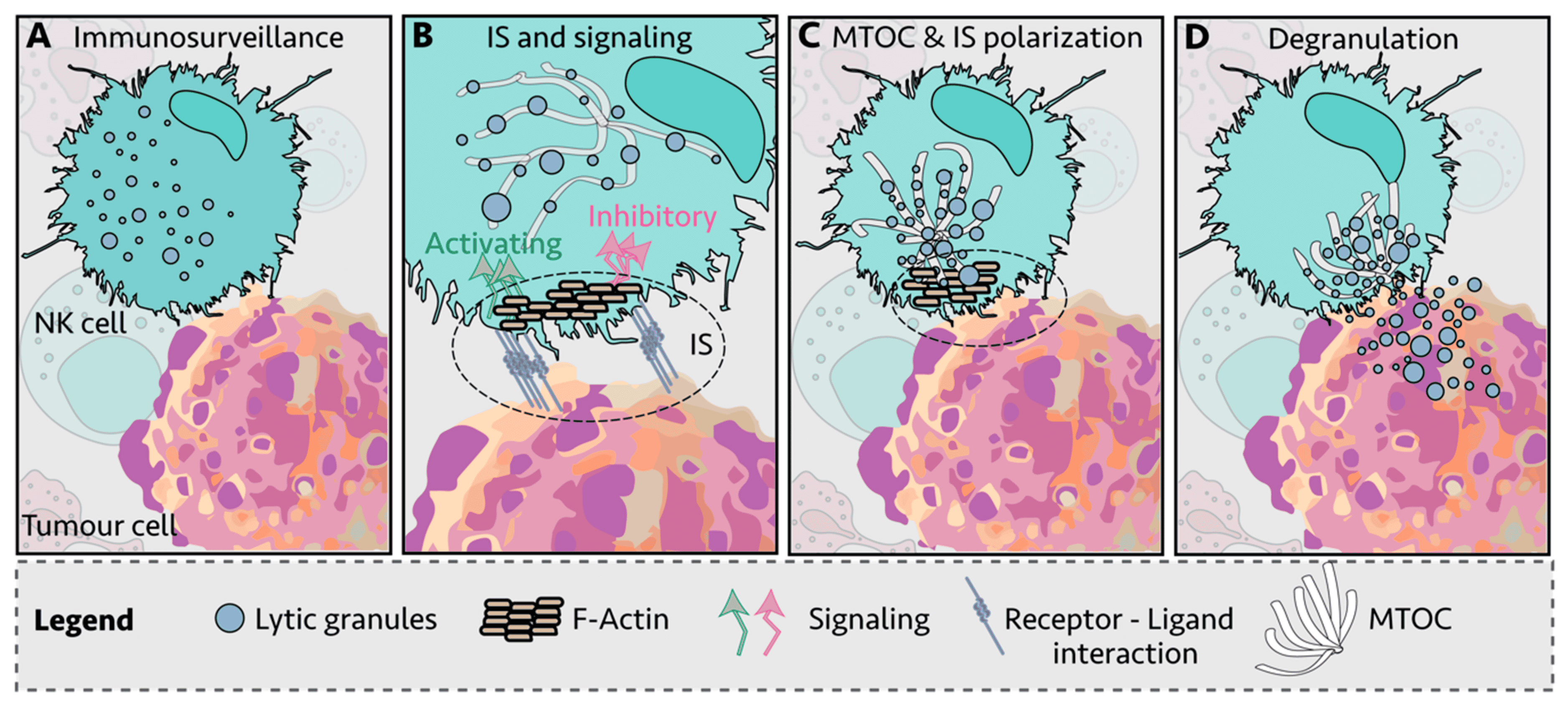

NK cells form immunological synapses (IS) between themselves and target cells to direct cytotoxic activity in a coordinated manner (Figure 8). The NK cell binds to the target cell with integrin and adhesion molecules. This drives intracellular NK cell remodeling by the recruitment of F-actin and the engagement of inhibitory/activator receptors at the IS (Figure 8B). If these receptors’ output activates the NK cell, lytic granules within the NK cell move along the microtubules towards the microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) at the IS (Figure 8C) before being released into the target cell through the cell membrane (Figure 8D).

Figure 8: The formation of the immunological synapse (IS) between an NK cell and a tumor cell and the release of cytolytic mediators into the target cell. Reproduced under Creative Commons 4.0 CC BY from 25.

Markers of the Immunological Synapse

Lytic granules of the IS contain perforin and granzyme B (GzB). Perforin is a glycoprotein released from CD8+ T cells and NKs that acts to kill target cells by the formation of pores in their cell membranes, disrupting mineral homeostasis and inducing pro-apoptotic pathways.26,27 GzB is a serine protease released by activated CD8+ T cells and NK cells.28 Unlike perforin, GzB release requires two checks to be made: MHC antigen presentation and a secondary signal from IL-12 or IFN-γ.29,30 GzB enters the target cell’s cytoplasm, where it disrupts various proteins, eventually leading to cell death.28

Through the close proximity of cells in the immunological synapse, NK cells also kill by the direct contact of ‘death factors’ inducing apoptosis in target cells, the second major mechanism through which NK cells mediate cytotoxicity alongside ADCC.

Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and FasL (CD95L) are both members of the TNF superfamily. These factors induce apoptosis in tumor and virus-infected cells with a complicated series of checks and balances to prevent unintentional killing. However, TRAIL is less harmful to healthy tissues driving interest in its therapeutic potential.31

TRAIL induces apoptosis through interaction with its receptors on target cells which leads to the recruitment of apoptosis molecules in target cells and their death.32 TRAIL is upregulated on NK cells in response to IFN-γ and is also expressed on cytotoxic T cells.33-35

FasL is a transmembrane protein expressed in NK cells, T cells and macrophages that drives apoptosis in target cells upon binding to the Fas/ CD95 receptor expressed on most tissues.36,37

Figure 9: IHC of human tonsil tissue stained with Anti-Fas Ligand Antibody [FASLG/4453] (A277667).

Figure 10: IHC of human spleen tissue stained with Anti-Perforin Antibody [PRF1/2470] (A249713).

NK cells mediate their effector activity through the release of cytokines and chemokines or by direct cytotoxic attack, often without the need for recognition of a specific antigen.38 Instead, NK cells detect aberrant cells and microbes through various cell surface receptors. Most of these receptors are also expressed on other cells such as T cells (e.g. Toll-like receptors (TLR)), with the exception of the NK cell-specific natural cytotoxicity receptors (NCRs).39 These receptors, instead of detecting antigens, detect signs of distress/stress or non-self ligands from pathogens. Interactions between NCRs and their ligands dictate activation/quiescent states of NK cells and form a complex system of activating and inhibitory signaling to prevent the targeting of healthy cells (Table 3). This system is further complicated by the activity of cytokines and chemokines and their receptors.

| Type of Receptor | NK Cell Receptor | Corresponding Target Cell Receptor |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitory | KIR-L | HLA-A, B and C |

| LAIR-1 | Collagen | |

| CD94-NKG2A | HLA-E | |

| SIGLEC3, 7, 9 | Sialic acid | |

| KLRG1 | Cadherins | |

| NKR-P1A | LLT-1 | |

| LILRB1 | HLA class 1 | |

| Activating or Inhibitory | CD244 (2B4) | CD48 |

| Activating receptors, adhesion or co-stimulation molecules | SLAMF7 (CD319) | SLAMF7 (CD319) |

| α4β1 integrin | VCAM-1 | |

| β2 integrins (CD11a-CD18, CD11b-CD18, CD11c-CD18) | ICAM-1 (CD54) ICAM-2 (CD102) CD23 iC3b… | |

| CD226 | Nectin-2 (CD112) Poliovirus receptor (PVR, CD155) | |

| CRTAM | CADM1 (Necl2) | |

| CD27 | CD70 | |

| CD16 | IgG | |

| NKp46 | Viral hemagglutinins | |

| KIR-S | HLA-C | |

| CD94-NKG2C | HLA-E | |

| CD94-NKG2E | HLA-E | |

| NKG2D | ULBP (RAET) MICA MICB | |

| SLAMF6 | SLAMF6 | |

| PEN-5 | L-selectin | |

| CD96 | PVR (CD155) | |

| NKp80 | CLEC2B (AICL) | |

| CD100 | CD72 | |

| NKp30 | Cytomegalovirus pp65 BAG6 (BAT3) | |

| NKp44 | Viral hemagglutinins | |

| PSG1 (CD66) | PSG1 (CD66) | |

| CD160 | HLA-C |

Table 3: The complicated network of (some of the) activating and inhibitory signals between NK cells and target cells that are integrated to determine NK cell activation or deactivation in humans. Cytokines, chemokines and their receptors are not shown, but also strongly influence NK cell activity. Adapted from 40

Inhibitory and Activator Receptors as NK Markers

An example of an inhibitory receptor is the killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIRs) family. Expressed on NK and T cells, these receptors block NK cell activation, and therefore killing, upon binding to HLA class 1 (HLA-A, -B and -C) molecules.41 The structure of KIRs differs based on the HLA subtype they bind: three IG-like subdomains for HLA-B alleles, two for HLA-A and -C.42,43 Cells that lose these molecules – tumor-transformed and viral-infected – are swiftly killed. KIRs are not expressed in the mouse.44

CD94 is a protein that forms heterodimeric receptors with the NKG2 family and is expressed mostly on CD56bright (and to a lesser extent on CD56dim) NK cells, as well as adaptive NK cells.11 CD94 is also co-expressed on CD8 T cells with NKG2A.45 CD94 is associated with inhibitory or activator cytotoxic activity depending on the heterodimer formed: CD94/NKG2A and CD94/NKG2C, respectively.11 These heterodimers recognize HLA-E (class 1).15 Alongside effects on cytotoxic activity, CD94 may also regulate NK survival with its expression associated with increased NK apoptosis.46

CD8 is a marker associated mostly with T cells. However, NK cells can also express the co-receptor (termed NK8+ cells), though at lower levels compared to T cells.47 These cells are associated with having increased expression of the inhibitory receptors ILT2, KIR2DL4 and increased expression of the activator receptor NKG2D. NK8+ cells have been shown to be able to suppress activation and proliferation of CD4+, but not CD8+ T cells, most likely through reduced HLA-G-mediated NK suppression.47

In contrast to circulating cNK cells, tissue-resident NK cells (trNK cells) are found in tissues throughout the body, including non-immune tissues such as the liver, lung, small intestine and uterus. Development of these is poorly understood and they may develop from different progenitors and require distinct cues to cNK cells.48

Key tissue residency markers include CD56bright, CD16-, CD69+, CD103+, CD49a+, and CXCR6+, with low expression of perforin and granzyme B.49

trNK cells can also exhibit tissue-specific markers to reflect tissue-specific functions, such as placental vascular remodeling in the uterus. Specific KIR expression often differs between organs, while CD56 expression is one of the few consistent markers across liver, lung and uterine trNK cells 48.

Diagrams created with BioRender.com.

![Flow cytometry - Anti-NCAM1 Antibody [LT56] (APC) (A86431)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/86/A86431_644.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Flow cytometry - Anti-CD16 Antibody [LNK16] (A85767)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/85/A85767_213.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Flow cytometry - Anti-CD57 Antibody [TB01] (A86858)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/86/A86858_934.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Flow cytometry - Anti-CD94 Antibody [HP-3D9] (PE) (A86325)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/86/A86325_572.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC - Anti-Fas Ligand Antibody [FASLG/4453] (A277667)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/277/A277667_2.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC - Anti-Perforin Antibody [PRF1/2470] (A249713)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/249/A249713_1.jpg?profile=product_image)