Heather Van Epps, PhD | 6th March 2025

Neutrophils are a population of granulocytic cell characterized by unique multi-lobed nuclei and abundant granules. Neutrophils are the most abundant subset of white blood cell in humans (50-70% of all leukocytes) and are best known for their pivotal role in innate immune defenses. Discovered in the late 1800s by Ehrlich and Metchnikoff, neutrophils were long thought to be terminally differentiated innate cells with a singular function: to seek out and destroy extracellular invaders by a variety of mechanisms including phagocytosis, degranulation, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation.1 However, more recent studies have revealed that these cells display remarkable phenotypic and functional plasticity, with diverse roles in bone marrow, blood and tissues, both at steady-state and during stress.1-6

Neutrophils – also known as polymorphonuclear neutrophils or PMNs – have traditionally been difficult to study owing to their short half-life (mostly <1 day), post-mitotic nature, and sensitivity to manipulation. However, sophisticated genetic, genomic, and single-cell technologies—as well as the appreciation that neutrophils can survive for up to 5 days in certain contexts—have dramatically increased our understanding of neutrophil diversity and functional plasticity. There are a variety of markers that identify neutrophils at various stages of maturation and in specific contexts that allow researchers to study the phenotype and function of these cells in health and disease.

Neutrophils are abundant in the circulation, comprising 50-70% of all circulating leukocytes in humans (10-20% in mice).5,7 These cells are also found in virtually all tissues of the body, where they exhibit a range of phenotypes and functions, including many that are unrelated to immune defenses. Like M1 and M2 macrophages, neutrophils can have both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory functions, and they have important roles in homeostatic processes in tissues.

The phenotype and function of neutrophils is dictated by their state of maturation, migration status, and location in bone marrow, blood, or tissues (Table 1). Various subsets of neutrophils have been described, including low-density neutrophils (LDN), granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (g-MDSC or PMN-MDSC), and tumor-associated neutrophils (TAN)—with many studies using distinct terms to describe similar neutrophil populations. Indeed, a universally accepted neutrophil nomenclature is lacking,8 and whether the various neutrophil subsets that have been described represent durable populations or simply reflect differential states of maturation or activation dictated by environmental cues is a matter of ongoing debate and investigation.

| Cell Stage | Location | Function | Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSPCs, GMPs, Pre-neutrophils | Bone marrow | Granulopoiesis | Growth factors (e.g. G-CSF, GM-CSF) Cytokines, chemokines (e.g. CXCL12, IL-1β, IL-6) Transcription factors |

| Immature neutrophils | Response to stress (e.g. cancer, infection) | ||

| Mature neutrophils | Immune defense, response to stress | ||

| Circulating neutrophils | Blood | Immune defense, acute inflammation | Endotoxins and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) Circadian-controlled transcription factors and chemokine receptors |

| Aged neutrophils | Removal from blood, circadian immune defense, vascular protection | ||

| Tissue neutrophils | Tissues | Anticipation of infection, tissue-specific roles such as pulmonary transcription, regulation of bone marrow niches | Tissue-derived signals Microbiotal metabolites |

Table 1: Neutrophil heterogeneity in location, function and regulation. Adapted from 5

Several molecules are expressed by most neutrophil populations and are used in various combinations to identify mature neutrophils in blood and tissues, and these markers vary by species. Pan neutrophil markers that identify most neutrophils in the blood and tissues include:

Mouse

Human

None of these markers is unique to neutrophils, however. For example, CD11b is also expressed on other myeloid cells, and CD62L is expressed on naive T cells.

Figure 1: IHC of human tonsil stained with Anti-CD11b Antibody [ITGAM/3340] (A249064).

Figure 2: Flow cytometry analysis of human peripheral whole blood stained with Anti-CD15 Antibody [MEM-158] (FITC) (A85936).

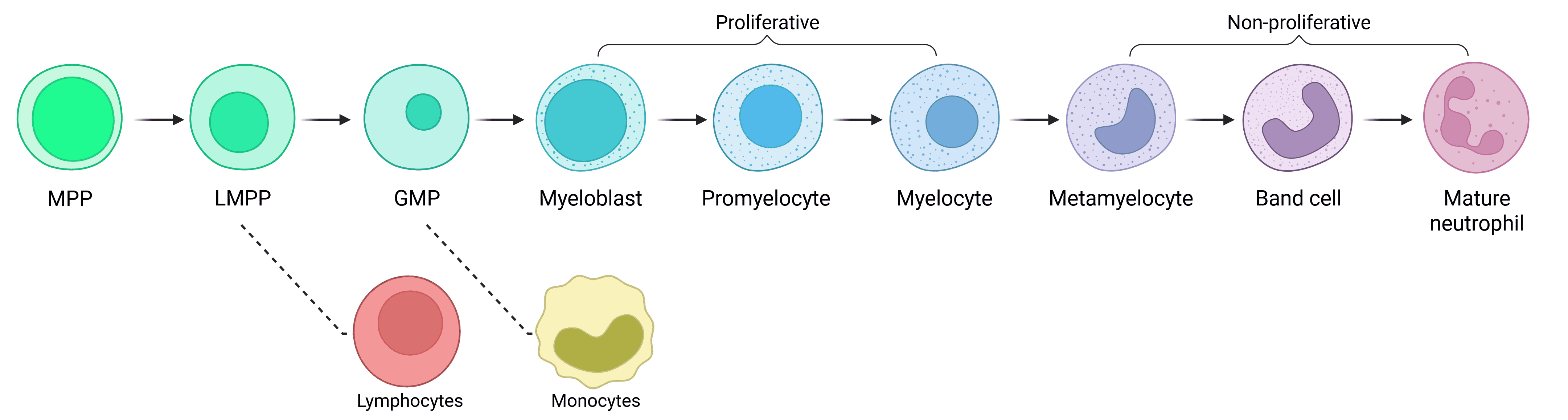

Neutrophils are continuously produced in the bone marrow from granulocyte–monocyte progenitors (GMPs) via a stepwise process called granulopoiesis (Figure 3). At steady-state, neutrophils are released into the bloodstream as mature cells; however, immature neutrophils are also released from the bone marrow in response to inflammatory signals. Neutrophil production can be augmented during states of inflammation by a process called emergency granulopoiesis.

Figure 3: Neutrophil development via granulopoiesis. Neutrophils develop in the bone marrow from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) via various progenitor subtypes, ultimately released into the blood as mature neutrophils. Based on transcriptional profiles, monocytes are the closest related cells to neutrophils. GMP: granulocyte/monocyte progenitor; LMPP: lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitor; MPP: multipotent progenitor.

Expression of surface markers changes during neutrophil maturation, with certain markers such as CD49d (Integrin alpha 4) expressed only on human pre-neutrophils and others (e.g., CD10) expressed only on fully mature human neutrophils. Levels of expression of cell surface proteins vary during neutrophil maturation (Table 2), and these markers differ between humans and mice (Table 3).5,6

| Myeloblast | Promyelocyte | Myelocyte | Metamyelocyte | Band cell | Neutrophil | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-DR | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| CD34 | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| CD49d | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | - | - |

| CD15 | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| CD33 | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | + | + |

| CD62L | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| CXCR2 | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| CXCR4 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| CD18 | ++ | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| CD66b | - | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| CD24 | - | - | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| CD11b | - | - | +/++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| CD11c | - | - | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| CD177 | - | - | + | + | + | + |

| CD16 | - | - | - | + | ++ | +++ |

| CD87 | - | - | - | - | ++ | ++ |

| CD35 | - | - | - | - | ++ | ++ |

| CD10 | - | - | - | - | - | ++ |

Table 2: Expression of surface markers during granulopoiesis in humans. Expression key: (-) Not expressed (+) Low (++) Medium (+++) High. Based on data from 8

| Pre-neutrophil | Immature neutrophil | Mature neutrophil | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | LIN- CD117+ Siglec-F- CD11b+ Ly6G+ CXCR4+ | LIN- CD115- Siglec-F- CD11b+ Ly6G+ CXCR2- CD101- | LIN- CD115- Siglec-F- CD11b+ Ly6G+ CXCR2+ CD101+ |

| Human | LIN- CD66b+ CD15+ CD33mid CD49dmid CD101- | LIN- CD66b+ CD15+ CD33mid CD49- CD101mid CD10- CD16mid | LIN- CD66b+ CD15+ CD33mid CD49- CD101mid CD10+ CD16hi |

Table 3: Markers of different stages of neutrophil development in mouse and human. Adapted from 5

Mature neutrophils are continuously released from the bone marrow into the bloodstream, but the phenotype of mature neutrophils is not uniform. Studies of mouse and human neutrophils have identified specific subpopulations within the circulating PMN pool at steady state.6 For example, one study identified a population of pro-angiogenic neutrophils in mouse and human blood that express CD49d, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (VEGFR1) and the chemokine receptor CXCR4.9

Mature neutrophils in the blood can be primed by a variety of stimuli, including inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, mitochondrial contents, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs).10,11 In response to priming, neutrophils upregulate molecules involved in extravasation into tissues, including CD11b, CD63, and CD66a, with concomitant increases in functional capacity, including ROS production and phagocytosis.10

The phenotype of circulating, mature neutrophils is also regulated by a circadian process of neutrophil aging, in which aged PMNs eventually return to the bone marrow, liver or spleen for clearance by macrophages.5,12 Neutrophil aging is characterized by diurnal changes in expression of surface receptors, with levels of CXCR4 and CD11b increasing and levels of CD62L decreasing as the cells age. 5

Figure 4: IHC of human tonsil stained with Anti-CD63 Antibody [MX-49.129.5] (A250748).

Figure 5: Flow cytometry analysis of human peripheral whole blood stained with Anti-CD62L Antibody [LT-TD180] (FITC) (A85808).

Neutrophils migrate from the bloodstream into tissues, both at steady-state and in response to infection or disease. Most circulating neutrophils express low levels of ICAM-1 and high levels of CXCR1, whereas PMN found in tissues express low levels of both molecules.6,13 Upregulation of specific adhesion molecules that are typically low in circulating neutrophils has been shown to be necessary for migration into distinct tissues; for example, L-selectin (CD62L) is required for neutrophil migration to the spleen, and ICAM-1 for migration to the liver.15

Neutrophils can also migrate in the reverse direction—from tissues into blood—and these reverse migrated PMN have been shown to have the opposite phenotype (ICAM-1highCXCR1low) to most circulating PMNs.

Neutrophils are present in most tissues of the body, including blood, liver, lung, spleen, intestine, and skin,1,2 where they acquire new phenotypic and functional properties via transcriptional and epigenetic reprogramming in response to tissue-specific signals. For example:

Figure 6: IHC of human lymph node stained with Anti-ICAM1 Antibody [P2A4] (A248905).

Figure 7: Flow cytometry analysis of Expi293 cells transfected with human CXCR1 (blue) or with an irrelevant protein (red) stained with Recombinant Anti-CXCR1 Antibody [DMC470] (A318720).

Tumor-Associated Neutrophils (TANs)

Tumor-associated neutrophils (TAN) were first described in mice and were initially divided into functionally distinct tumor-suppressive (N1) and pro-tumor (N2) subtypes.7,16 In humans, TANs primarily function to promote tumor growth (i.e. N2), and clinical studies show that an increased neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with poor clinical outcomes in many cancer types in humans;17,19 human neutrophils can also help to restrain tumor growth in specific contexts.4

Other subsets of neutrophils, including immature neutrophils and interferon-γ (IFNγ)-activated neutrophils, have also been described in the tumor microenvironment in humans and mice.1 Whether different populations of TANs exert anti-tumor or pro-tumor functions depends in part on the tumor milieu. For example, TGFβ polarizes TANs toward a pro-tumorigenic phenotype. IFNγ, by contrast, induces anti-tumor responses in neutrophils, which can activate CD8+ T cells and render tumors responsive to anti-PD-1 therapy.1 Subsets of TANs are characterized by varying expression of neutrophils surface markers, which differ in mice and humans (Table 4).

| Immature neutrophils | Pro-tumor neutrophils | Anti-tumor neutrophils | IFN-stimulated neutrophils | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | Ly6G+ CD11b+ CD117+ CD170lo CD101- CD84+ JAML | Ly6G+ CD11b+ PD-L1+ CD170hi | Ly6G+ CD11b+ CD170lo CD170+ (in CRC) CD54+ CD16+ | Ly6G+ CD11b+ IFIT1 IRF7 RSAD2 | Human | CD66b+ CD11b+ CD117+ CD10- CD16int/lo LOX1+ CD84+ JAML | CD66b+ CD11b+ CD170hi PD-L1 | CD66b+ CD11b+ CD101+ CD177+ CD170lo CD54+ CD86+ HLA-DR+ CD15hi | CD66b+ CD11b+ IFIT1 IRF7 RSAD2 |

Table 4: Expression of surface markers on subsets of tumor-associated neutrophils. CRC: colorectal cancer. Adapted from 1

Neutrophil Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (PMN-MDSC)

Pro-tumor TANs with T-cell suppressor activity are often referred to as granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (g-MDSC or PMN-MDSC), although these cells can also be induced in response to inflammation and trauma.20 In mice, PMN-MDSC express CD11b, CD14, Ly6G and low levels of Ly6C;4,21 human PMN-MDSC markers include CD11b, CD33, CD15, LOX-1 (humans). Both mouse and human PMN-MDSC have been shown to express CD84, FATP2, and TRAIL-R25.4,22 It is important to note that there are no markers that definitively distinguish PMN-MDSC from other neutrophil populations, and the characterization of these cells relies on tests of their suppressive activity.6

Low-Density Neutrophils

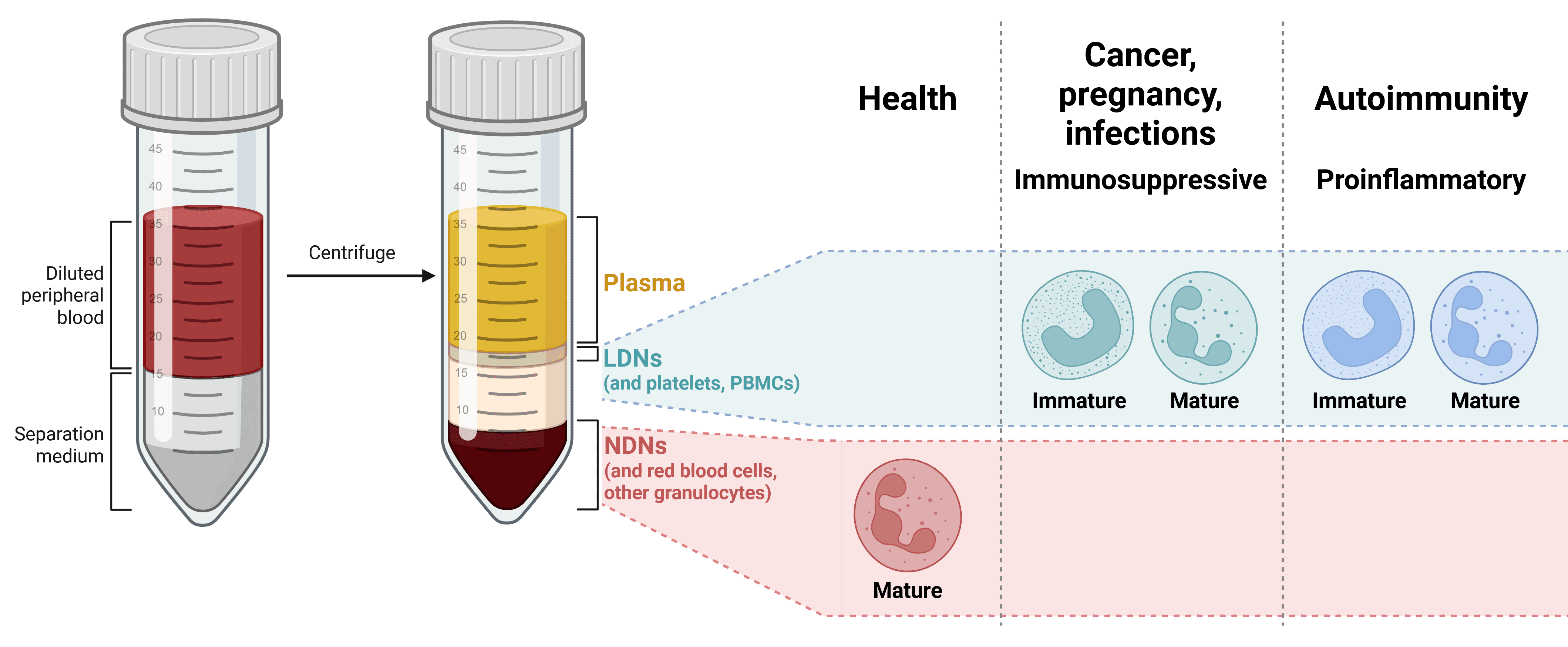

Low-density neutrophils (LDNs)—so called because they reside in the low-density fraction on density gradient fractionation—are a population of neutrophils first identified in patients with infections or inflammatory diseases and in cancer (noting that PMN-MDSC were initially thought to mostly reside within the low-density fraction). The phenotypic and functional distinction between LDNs and normal-density neutrophils (NDNs) is not completely clear, although LDNs appear to include both immature and mature PMNs, with many of the latter showing evidence of activation or degranulation. LDNs can have both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory functions (Figure 8).6 LDNs have been described as exhibiting higher levels of CD10, CD15, CD16b and CD66b than NDNs, though no markers have been identified yet to definitively distinguish LDNs from NDNs.23

Figure 8: LDN populations isolated from density gradient fractionation of blood. Two main LDN populations have been reported so far: immunosuppressive and proinflammatory, sometimes referred to as polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells (PMN-MDSCs) and low-density granulocytes (LDGs), respectively. Whether NDN populations fulfilling similar functions in people with these conditions also exist is currently unclear. Adapted from 6.

![IHC - Anti-CD11b Antibody [ITGAM/3340] (A249064)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/249/A249064_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Flow cytometry - Anti-CD15 Antibody [MEM-158] (FITC) (A85936)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/85/A85936_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC - Anti-CD63 Antibody [MX-49.129.5] (A250748)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/250/A250748_2.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Flow cytometry - Anti-CD62L Antibody [LT-TD180] (FITC) (A85808)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/85/A85808_240.jpg?profile=product_image)

![IHC - Anti-ICAM1 Antibody [P2A4] (A248905)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/248/A248905_1.jpg?profile=product_image)

![Flow cytometry - Recombinant Anti-CXCR1 Antibody [DMC470] (A318720)](https://cdn.antibodies.com/image/catalog/318/A318720_1.jpg?profile=product_image)